Who was Miguel Hidalgo? To put it in perspective: George Washington is the father of American independence; Mahatma Gandhi symbolizes India’s struggle against British colonial rule. Mexico has Miguel Hidalgo. Yet outside Mexico, few recognize his name. Figures like Benito Juárez—who famously dubbed himself the consummator of Mexico’s “second independence”—or Pancho Villa enjoy far more international fame. But Hidalgo, a priest who ignited Mexico’s War of Independence in 1810, remains a fascinating, if not outright antiheroic, figure for those willing to look closer.

From Revered Leader to Scorned Martyr

Hidalgo’s legacy is complicated. As a priest, he was known for his encyclopedic knowledge, fluency in several languages, artistic talents, and concern for the poor. Yet he was also infamous for multiple affairs, a fondness for revelry and gambling, and, once the war began, his controversial decision to allow the unruly revolutionary forces to commit massacres against Spaniards—women and children included. One stark example: in September 1810, as the revolutionary mob neared Guanajuato, hundreds of frightened families locked themselves inside the Alhóndiga—a fortified granary. Hidalgo and his enraged followers set fire to the doors, stormed the building, slaughtered the occupants, and then looted and razed the city.

Hidalgo tolerated these excesses, a fact he later acknowledged during his trial. Captured in 1811, Hidalgo was dragged on a grueling journey to the remote city of Chihuahua, where he was executed inside what is now the state government palace. A small niche marks the exact site of his execution. A Tarahumara indigenous man reportedly severed Hidalgo’s head with a single blow, earning twenty pesos for the gruesome task. But Hidalgo’s remains didn’t stay there. His head was salted and sent back to central Mexico, where it was locked inside a cage and hung atop the very building in Guanajuato where the massacre occurred. For ten years, it remained exposed to the elements and birds—a brutal warning to potential rebels. Father Hidalgo received the ultimate punishment: the dishonor of not having a proper burial, and worse, that the only face the public would remember was that of a sun-bleached skull.

When independence finally triumphed, the new Mexican government ordered the cage removed and the head, now faceless, given a hero’s burial. That should have been the end of it all. But it was only the beginning.

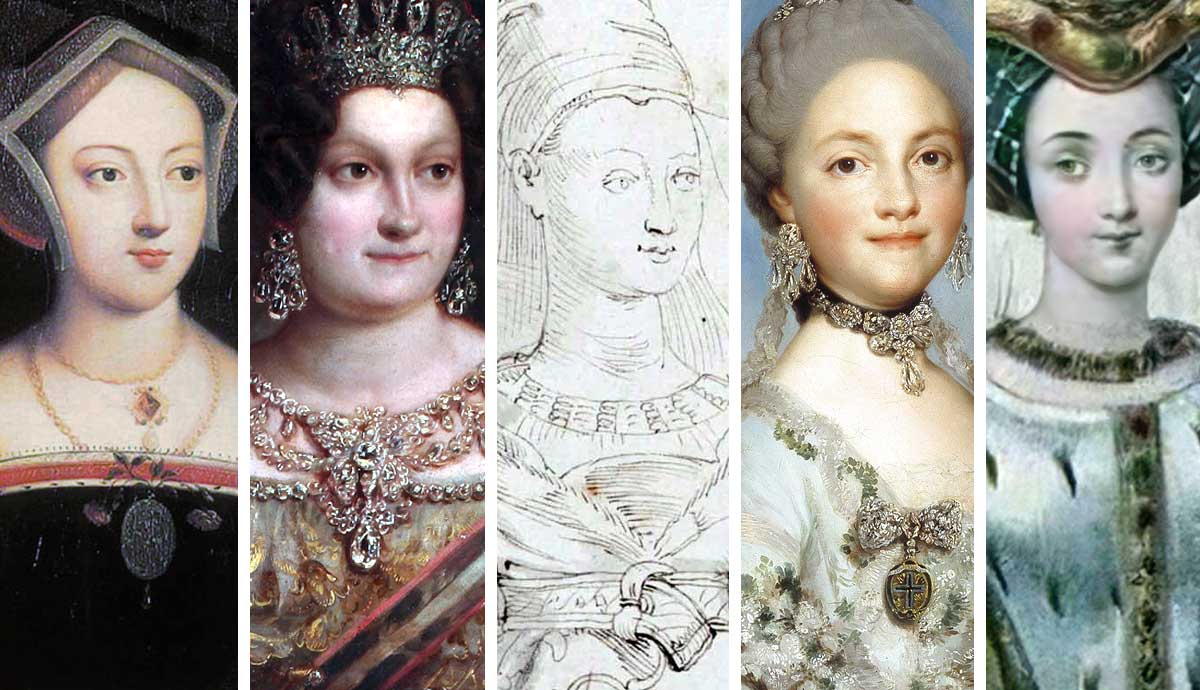

Portrait or Pretender? The Austrian Priest Legend

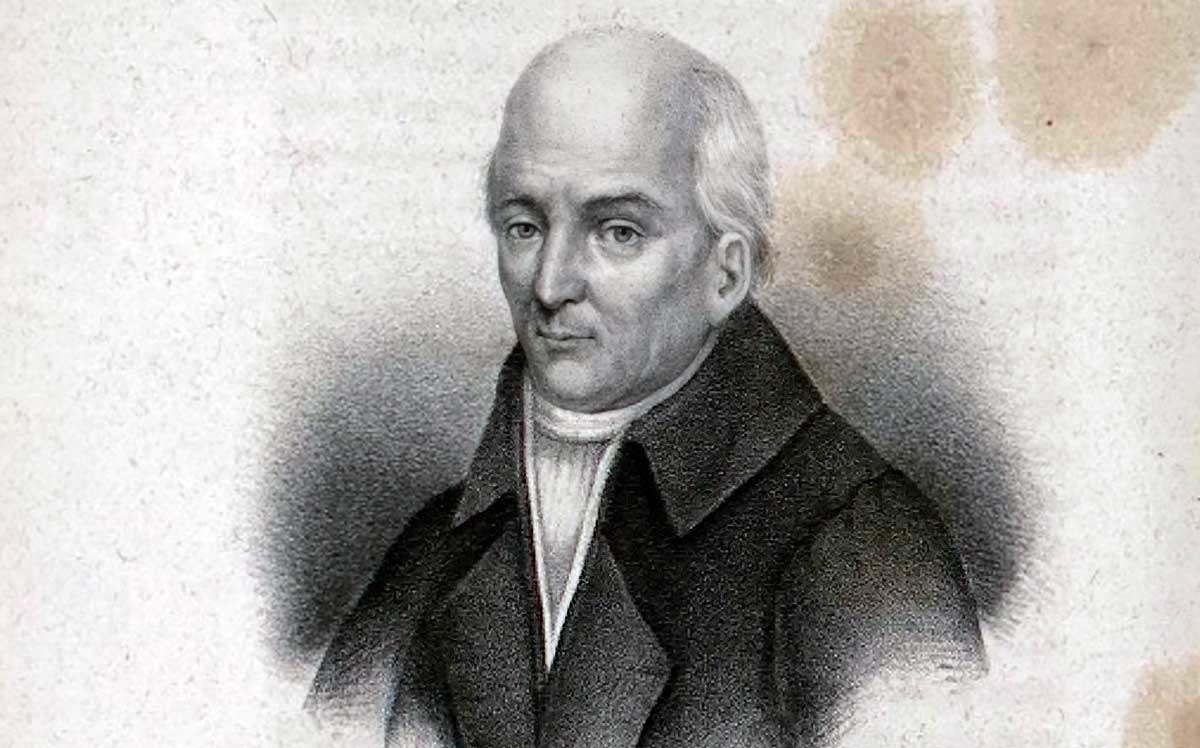

There are no photographs of Father Miguel Hidalgo—no images of his head or the infamous Alhóndiga cage. Photography arrived in Mexico nearly two decades later, in the 1840s. Hidalgo’s visage—a man entering old age, graying, nearly bald, with a noble, kindly expression—was immortalized instead in paintings by a young artist called Joaquín Ramírez. One such portrait hung in Mexico City’s National Palace in 1865.

Fast forward to the turn of the millennium, an era ripe with rumors and historical revisionism. A persistent whisper emerged: since Hidalgo was never painted from life—true—no one really knew what Mexico’s founding father looked like—half true. Worse yet, the widely accepted image by Ramírez was said to be a colossal fraud, actually a portrait of an Austrian priest. This rumor was fueled by Luis González de Alba, a former student activist, ex-convict, psychologist, science popularizer, and noted provocateur.

According to González de Alba, when Emperor Maximilian of Austria sought to create an official pantheon of Mexican heroes, he found no known images of Hidalgo and thus he enlisted an Austrian priest from his entourage to sit for what would, quite curiously, become the portrait of Mexico’s founding father. The story goes that this was how Mexico got its iconic image of the man who sparked its independence. Many Mexicans still believe this today.

“They Lied to Us”: The Bicentennial Controversy

The Bicentennial in 2010 reignited the debate. The rumor became so widespread that some, including a state governor, called for a crusade to remove Hidalgo’s portrait from textbooks and find the “true” face of the nation´s Founding Father. Important newspapers and TV channels reproduced the story. A headline blared loudly in one particularly vocal newspaper: “They lied to us.” According to the myth, Mexicans had been paying homage to a Belgian or Austrian priest who never did anything for the country.

Like all great conspiracies, this one refuses to die and has resurfaced repeatedly. But is it true? Is Hidalgo’s face really based on a European priest, not the revolutionary whose head was once hung as a warning in central Mexico?

In Search of Miguel Hidalgo’s True Face

The 1856 Postage Stamp

In fact, the “Austrian priest” theory collapses quite quickly. Mexico issued its first postage stamp on August 1, 1856—a half real blue stamp crudely printed and roughly cut—but it unmistakably depicts Miguel Hidalgo. A quick glance reveals the same man Ramírez painted a decade later. This stamp proves Hidalgo’s image wasn’t simply concocted in 1865.

One might argue that the balding man with the aquiline nose and priestly collar was simply a product of the engraver’s imagination. So to determine whether this face had a historical basis—and wasn’t merely artistic license—historians need to look further back, to earlier sources that suggest the image was not conjured from thin air.

Lucas Alamán’s Testimony

Lucas Alamán, a prominent Mexican thinker, politician, and historian, wrote one of the country’s first histories when independent Mexico was barely three decades old. Many witnesses of the revolutionary war were still alive.

From the first edition (1849), Alamán’s history included a portrait of Hidalgo nearly identical to the postage stamp and Ramírez’s painting. And in fact, he took that illustration from an even older book. When Alamán’s history and the portrait appeared, hardly a generation had passed since Hidalgo’s death, and many still remembered him personally. Remarkably, Alamán met Hidalgo himself as a 17-year-old in Guanajuato—the site of the massacre. His physical description leaves little doubt that, while no photograph existed, both the postage stamp and Ramírez’s portrait capture Hidalgo’s likeness fairly well:

“I had the opportunity to see and speak with Hidalgo often—he was a frequent visitor to my home,” Alamán wrote. “He was of medium height, stooped shoulders, dark complexion, lively green eyes, head bowed slightly toward his chest, quite gray and bald, seemingly over sixty, yet vigorous though not quick in movement; taciturn in everyday dealings but lively in debate, much like a scholar in heated argument. He was modestly dressed, wearing the typical garb of small-town priests.”

The Divergent Fates of Hidalgo’s Likeness and His Remains

While Hidalgo’s face has followed a relatively smooth trajectory—traced through paintings, engravings, postage stamps, eyewitness descriptions, and schoolbook illustrations—his skull has led a far more erratic existence. One was fashioned by memory and myth, stabilized by artistic convention and national need; the other wandered through crypts, display cases, and forgotten vaults, marked by uncertainty and decay. The face became iconic, almost serene in its reproducibility; the skull, meanwhile, remained elusive, physically real yet symbolically unstable. And yet, in 2010, on the bicentennial of Mexican independence, these two diverging paths unexpectedly met.

When Mexican independence was secured, the cage holding Hidalgo’s skull was removed by the victors around early 1821. The head was buried alongside other revolutionary heroes in a city cemetery, where they remained until 1823. That year, a solemn procession moved the skulls to Mexico City’s cathedral. There, according to contemporary accounts, bones were jumbled in a niche later infested with cobwebs and rats. In 1895, the bones were exhumed, cleaned, sun-dried, photographed, and reburied.

Their final resting place was secured in the 1920s, beneath the iconic Independence Angel column. During the 2010 bicentennial, the relics were restored and studied scientifically. Some voices called for modern forensic techniques to reconstruct Hidalgo’s face.

But the results brought embarrassment. First, the bones of Vicente Guerrero—the man who finally secured independence in 1821—showed no evidence of execution, contrary to legend. Mariano Matamoros’s remains turned out to be those of a woman. And Hidalgo’s skull, marked “HA,” was identified with more certainty but was heavily damaged after years exposed to the elements—his face entirely lost, replaced by a hollow void. The dream of bioarchaeology resurrecting Hidalgo vanished.

A Nation’s Father, Restored: Truth Beyond the Faceless Skull

Miguel Hidalgo’s head has had an eerie journey. Severed from his body, it traveled across Mexico, displayed in various towns before being hoisted high to dry in the open air, then shuffled back and forth across the country. For decades, his skull and the bones of other freedom fighters lay forgotten in a humid, unlit chamber of Mexico´s cathedral, jumbled with other remains in a damp recess no one wanted to enter. From time to time, concerned citizens petitioned to have them moved to a more dignified resting place, but the bureaucracy proved as unyielding as stone. No one claimed responsibility, and every official insisted the task fell outside their jurisdiction.

One can’t help but wonder if the Father of the Nation’s ghost rebelled against this barbaric fate, spawning the enduring rumor that no one could ever know his true face.

But thanks to a young man who saw him in Guanajuato—the teenager Lucas Alamán, who grew into a scholar and historian—we can confidently reject the myth that Hidalgo’s features were lost forever. His faceless skull may stare darkly into the void, but the historical person and his face remain recoverable.

Controversial man, yes. Antihero, perhaps. Father of the Nation, beyond doubt.