From about 3000 BCE until about the collapse of the Bronze Age in 1200 BCE, the Minoans were a premier Aegean culture. Located on the island of Crete, the Minoan people developed sophisticated trade and diplomatic ties with other cultures, such as the Egyptians. With the wealth they gained from those ties, the Minoans created beautiful art and architecture and invented what was perhaps the world’s first spectator sports. The Minoans truly built Europe’s first civilization, which would later influence the classical Greeks. But as great as the Minoan culture was, it remains mysterious. The Minoan written language is still undeciphered, and the reasons for the decline of their culture are not completely known. The Minoans may be one of the most important Bronze Age cultures, but they are also one of the most enigmatic.

Defining Minoan Culture

Despite evidence of the Minoan culture being displayed in ruins throughout the island of Crete, it was a complete mystery until the early 20th century. It was at that time that British archaeologist Arthur Evans (1851-1941) first began his excavations of the palace of Knossos. Evans eventually named what was at the time a virtually unknown Aegean culture, the “Minoans,” as Crete was believed to have been the home of the legendary King Minos.

Despite a lack of textual evidence, Evans was able to develop an accurate Minoan chronology based on archaeological discoveries. He eventually divided Minoan chronology into three primary phases, with several subdivisions. The Early Minoan period lasted from about 3000 to 2200 BCE. This was followed by the Middle Minoan period from 2200 to 1600 BCE, and finally the Late Minoan period, from 1700 to 1100 BCE.

The Minoan Language and Script (Linear A)

One of the many cultural hallmarks that many experts consider a prerequisite to civilization is writing. Writing allows people to record economic transactions as well as their history and myths. The Minoans developed a written language that is today known as Linear A. The language was used by the Minoans on Crete until about 1450 BCE, when it was then replaced by the proto-Greek language of Linear B.

Only about 50 words of Linear A have been deciphered, which has left a shroud of mystery over Minoan culture. Without knowing what language family Linear A belongs to, it is difficult to say if the Minoans were Indo-European, Semitic, or from another linguistic-cultural group. It is also difficult to determine details about the Minoan economy and foreign relations, but based on the archaeological evidence, it was likely relatively advanced.

Minoan Economy & Trade

When it came to the necessities, the Minoans were, for the most part, self-sufficient. They locally sourced the stone and timber used to build their magnificent palaces, and the same was true for their food. Most Minoans lived in the coastal cities, but the plains in Crete’s interior had a good climate for growing grains, and orchards were plentiful. The Minoans also raised bovines, as bulls were enmeshed in various aspects of their culture, and they were mariners and fishermen.

Although the Minoans could get the necessities from Crete, they needed to import luxury and prestige items from other lands.

The Minoans imported many metals to Crete. Tin was imported from either Central Europe, Etruria (northern Italy), or both. Mesopotamia was also an indirect source of tin. Silver was imported from other parts of the Aegean, including mainland Greece, and silver and gold were imported from Anatolia. Finally, the Minoans imported manufactured goods from Egypt and other places in the Near East. Egyptian scarabs and vessels dated as far back as Egypt’s 12th dynasty (c. 1985-1773 BCE) have been excavated on Crete.

It is important to note that the trade was not one-way. The tomb of the Egyptian high official, Menkheperrasaneb, depicts a group of foreigners bringing tribute. One of the tribute bearers is described as Wer Keftiu (Chief of the Keftiu/Aegeans/Minoans). The Minoan chief is depicted wearing a kilt with no shirt, reddish brown complexion, and long hair. He is carrying what appears to be a statue of a bull’s head on a plate with a piece of linen draped over one of his arms. This tomb has been dated to the 18th dynasty (c. 1479-1400 BCE) of the Egyptian New Kingdom.

Spending That Wealth: Minoan Palaces

It is easy to imagine Minoan port cities alive with trade in the Middle and Late Bronze ages. Although the Minoans’ ships were not unlike others at the time, their navy must have been impressive, and their diplomatic acumen was high. There is no evidence that Minoans were attacked by outside forces before the Late Bronze Age, and there is also no evidence that suggests they engaged in any military expeditions against others outside Crete. This is not to say that Crete was a peaceful utopia, but that the Minoans focused most of their resources on things other than war. In particular, they were able to build some of the most magnificent structures and art in the Bronze Age. Female figures featured heavily in Minoan art, leading some to suggest that it may have been a matriarchal society.

Nearly all the major Minoan settlements were located on or near the coast, with the biggest settlements having large palaces. Knossos is the best known of these palace settlements due to the extensive excavations that have been conducted there, but Mallia, Phaistos, Zakro, and others also had impressive palaces. The palace layout was similar at all of these sites. The palaces were multifunctional, combining economic, political, ceremonial, and manufacturing spaces. It appears that some spaces were off limits to the public, while the larger palaces, such as Knossos and Phaistos, had auditoriums. Minoan palaces were very different in form and function than those of the later Myceneans but more similar to their contemporaries in the Near East.

Minoan Frescoes

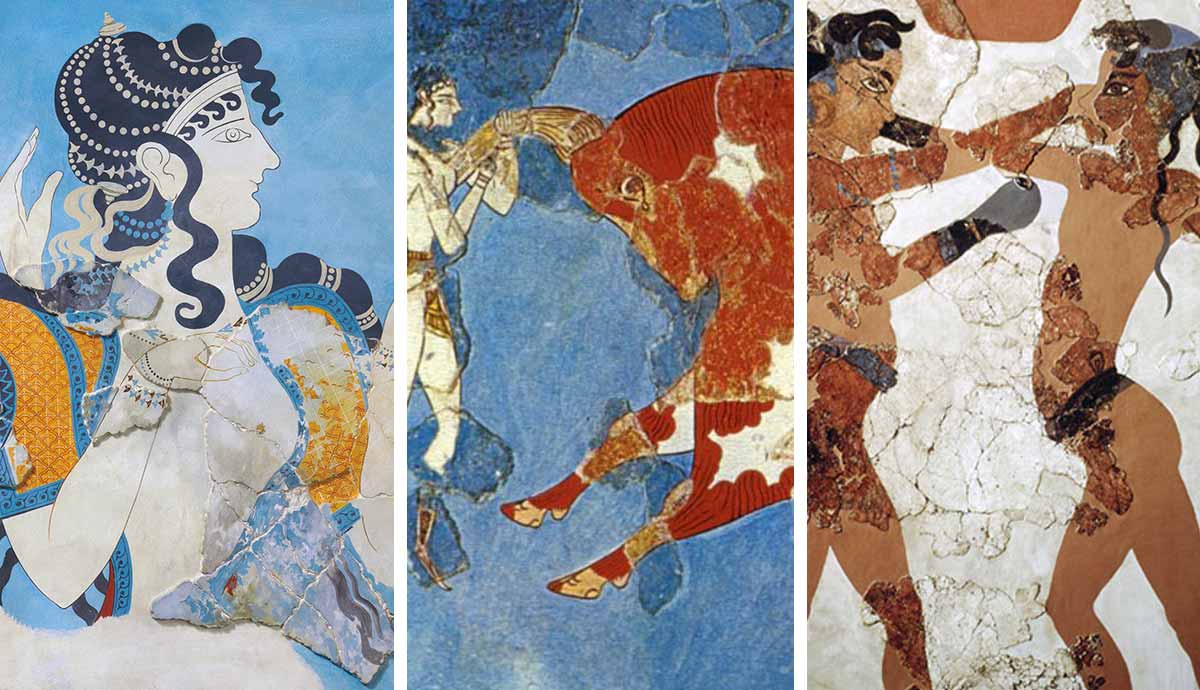

Minoan palaces were adorned with some of the most beautiful Bronze Age art. Among the most stunning are the many color frescoes that have been excavated in fragments and since reconstructed. Colorful scenes of dolphins, bare-breasted women, and athletes leaping over bulls are quite unlike anything from the Near East or Aegean. These tranquil scenes, along with the absence of martial themes, have led some modern scholars to suggest that the Minoans were a peace-loving society. While this is probably an oversimplification of Minoan society, it should be noted that no weapons discovered in Minoan sites predate the Late Minoan period (c. 1600 BCE).

Minoan Sporting Culture

The archaeological evidence demonstrates that the Minoans engaged in a number of organized sports, including boxing, wrestling, pankration, and bull jumping. The most important evidence is a vase from Hagia Triadha dated to about 1550 BCE. Often known as the “Boxer Rhyton,” the vase is an important piece of Aegean art due to the quality of the workmanship. The preservation has also allowed historians to reconstruct an important element of Minoan society.

The decoration on the vase includes sporting scenes in four registers. The top register depicts two men boxing with a column separating them from three other men who also appear to be boxing. Modern art historians have corroborated this interpretation by comparing it to a fresco from Thera dated to about 1625 BCE, which depicts two boys boxing. The second register of the Boxer Rhyton depicts bull-leaping. The third register shows four helmeted men with forearm guards and padded hands. Two are upright and two are on the ground. Men with no helmets, wrapped wrists, and possibly holding daggers or brass knuckles, are shown on the fourth register. This was possibly a depiction of a pankration event or a festival with a variety of events.

The Sport of Bull-Leaping

Other than the fresco from Thera mentioned above, there are no other examples of the activities on the Boxer Rhyton in Aegean art, with the exception of bull-leaping. Bull-leaping appears to have been an important activity in Minoan society that potentially had religious implications. Scenes of bull-leaping are depicted on numerous frescoes at different sites, but none are more famous than the “Toreador Fresco” in Knossos.

The Toreador Fresco depicts three different men leaping over a bull, starting from the left side of the fresco. The first man is shown grabbing the bull’s horn while the second man grabs the bull on the sides as he does a handstand. The third man is on his feet, facing the back of the bull. The standard interpretation is that the first toreador is attempting to control the bull by the horns while the second man performs the leap. Instead of the scene depicting three different toreadors, it could be read as three different stages in a bull leap. This theory would seem to fit the scene, although the second man having a darker complexion than the other two indicates that at least two of the three toreadors were different men.

Bull-leaping appears to have been a popular sport or ritual that the Minoans practiced at the height of their culture. But many details of the activity remain a mystery, specifically whether they really took place or if they were more metaphorical or even mythological in nature. Among those who believe bull-leaping was an actual part of Minoan culture is archaeologist James Thompson. He argued that in order for bull-leaping to have actually been practiced, a number of conditions needed to be met.

First, there would need to be a safe viewing area. Even if bull-leaping was a religious ritual, the priests and royalty would still need a viewing area to ensure the rituals were carried out properly. Second, the bull-leaping likely took place in the central courts of the palaces. Therefore, a safe passageway was needed to lead the bulls from their pens to the central court. Third, there obviously needs to be bull pens in the palace. Fourth, a system was required to keep the bulls in the central court once the event began. Finally, Thompson has argued that a vaulting device was needed to leap over the bulls. He argued that simply grabbing the bulls by the horns and performing a somersault was highly unlikely without the aid of a vaulting device. Based on his work, Thompson argued that the palaces at Knossos and Malia fit all five requirements.

As important as bull leaping was to the Minoans, its purpose remains an enigma. One argument is that it was done for purely athletic purposes as a spectator sport. The crowds would have been small and relegated to the nobility. Another theory is that they were religious in nature and part of a ritual, where the bulls were possibly sacrificed after the leaping event. The significance of bulls in Minoan art is quite apparent, suggesting that the Minoans viewed them as part of a greater cosmic significance. With that said, the ritual still could have been semi-public, and the event still would have been athletic in nature.

The Decline of Minoan Culture

At their peak, the Minoans colonized other parts of the Aegean, including the islands of Thera and Rhodes, and mainland Greece. But by about 1500 BCE, the Minoans had passed the zenith of their culture. A major volcanic eruption on Thera in about 1600 BCE may have been the catalyst for the Minoans’ decline. Some scholars believe that the Thera eruption was so destructive that it was the model for the Atlantis myth. Whether Atlantis was based on Minoan culture is open to discussion, but it is certain that the eruption would have devastated agriculture in the Aegean. The Minoans likely would have been forced to import food for some time.

One generation after the Thera eruption, most of the cities on Crete, with the curious exception of Knossos, were devastated by war. The background of this destruction is unknown. It may have been internal conflicts among the Minoans, or it may have been the first in a series of attacks from the north.

By the late second millennium, the Minoans were in the process of being eclipsed by the earliest Greek-speaking people, the Mycenaeans.

The Minoans may not have been a martial people, but the Mycenaeans certainly were. The Myceneans had totally conquered Crete by 1400 BCE, which raises an interesting point. Perhaps the theory that the Minoans were more concerned with beauty instead of war was true and played a role in their demise.

The Minoans were one of the most important Bronze Age cultures for a number of reasons. Their system of trade and diplomacy with the Near East anticipated later international systems. The Minoans’ love of beauty and art, as well as their development of ancient sports, certainly influenced the classical Greeks. But even as all of these attributes made Minoan culture great, they could not stop the collapse. A combination of environmental elements and outside human forces were likely the major culprits. But due to the lack of readable records, modern scholars may never know all the details of the Minoan collapse.