During the 13th century, the Mongols stormed onto the world stage to create one of the largest empires the world had ever seen. Despite their reputation for barbarity, the way they approached both warfare and governance was highly calculated and organized. The Mongols fostered a cult of fear based on their military prowess and use of psychological warfare. However, once the dust of conquest settled, the administrative side of the Mongols promoted the incorporation of their new subjects into the fabric of their societies, often maintaining pre-existing socioeconomic structures.

Military Innovation and Adoption by the Mongols

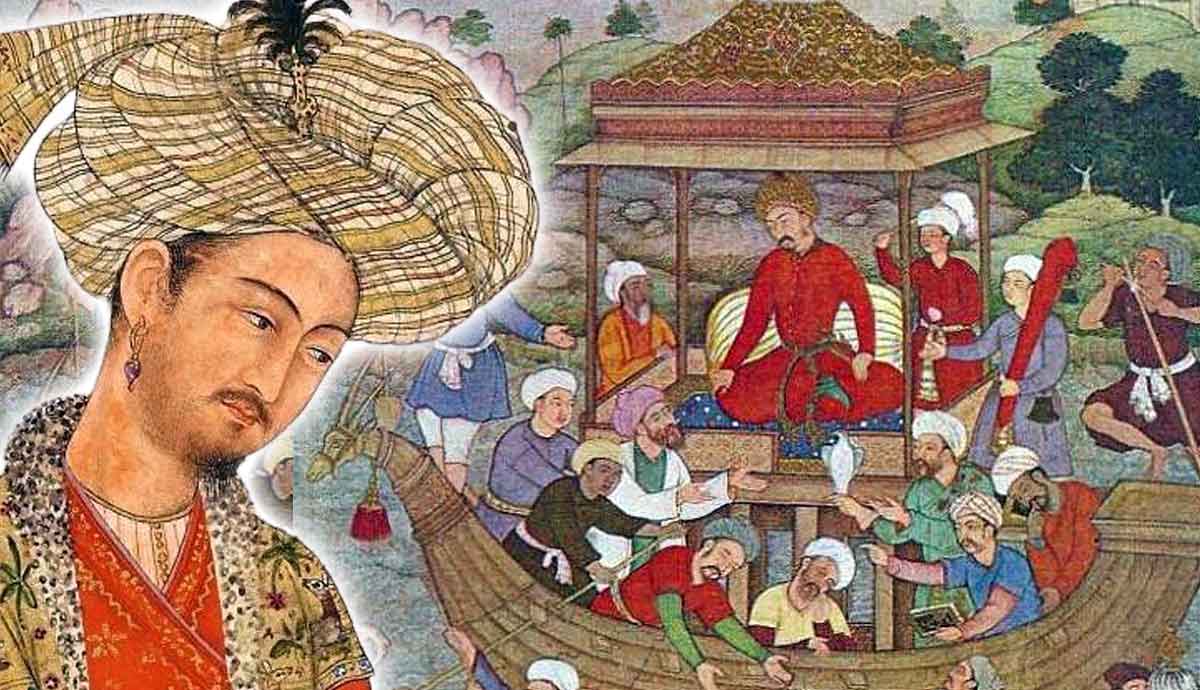

The Mongols, who conquered nearly all of Asia and parts of Eastern and Central Europe, were the result of the unification of separate nomadic tribes under the leadership of the chieftain Temüjin, who would become Genghis Khan, or the ‘universal ruler.’ Why did Temüjin make the decision to unify, and what were his motivations for conquest? The answers to these questions are closely related. Being nomadic peoples in the unforgiving conditions of 13th century Mongolia, they were reliant on trade with surrounding regions for resources that could help ensure their survival. In the south and east, the Jurchen Jin and Western Xia Dynasties of China began putting in place restrictions on trade with Mongol tribes.

Genghis could’ve seen this as an act of war, considering the reliance on non-Mongol trade partnerships for survival. Another reason behind unification and expansion wavered towards the spiritual—Temüjin believed he was assigned by the Mongol sky god Tengri, to unify not just the Mongols, but the entire world. It was his job to carry out this divine plan. The first step was to unify the Mongol tribes, then he could focus on outward expansion.

Mongol methods of warfare are credited with the success of Mongol expansion. Hailing from the steppes and mountainous region of Mongolia, the Mongols were famous for their skill as horse archers. One of their tactics that combined their horsemanship and archery skills was the arrow storm. Keeping their distance, sometimes from as far as 300 yards, Mongol archers would fire arrows at a high trajectory. The end result was a cloud, or storm, of arrows that would rise high above Mongol opponents and rain down on them. While terrifying, this method was not efficient in drawing blood, but that wasn’t the point. The intent was to scatter clusters of opponents who would be attacked on ground by lancers.

Another method of the Mongols was group fighting patterns. The Mongol armies were organized in decimalized units: groups of 10, 100, 1,000 or 10,000. This regimented system threw off targets of Mongol conquest such as the Japanese samurai. As opposed to the Mongols, samurai fought hand-to-hand combat, an approach to war influenced by Japanese perceptions of personal valor and honor. Thus, when the Mongols first invaded Hakata Bay in northwest Japan in 1274, their group fighting techniques posed a challenge to the highly skilled samurai.

Another favored tactic was the feigned retreat. In the event of failed frontal assaults, the Mongol vanguard would withdraw from the field in seeming disarray, enticing the enemy to pursue them. With the foes giving chase, other Mongol units would close in from behind and ambush them, trapping the enemy between a hammer and anvil.

Non-Native Tactics

Although the military tactics of the Mongols were skillful prior to expansion, part of the reason they were able to conquer parts of Asia and Europe so quickly was due to Chinese military technology. When the Mongols invaded northern China in 1211, they were introduced to new weapons: gunpowder and incendiary weapons. These were things like bombs made from flammable material that caught fire quickly to whatever it came into contact with. Other incendiary weapons using flammable material were also employed by the Chinese such as fire arrows and lances.

These weapons had been used in China as early as 1000 CE during the Song Dynasty. Allegedly, gunpowder was first discovered by an Indian Buddhist monk in the 7th century, who noticed a purple flame when a specific type of Chinese soil caught fire. This event helped identify a source of saltpeter, a natural mineral that serves as the basis for gunpowder. Although these weapons of fire were initially used against the Mongols, once they conquered the Jurchen Jin Dynasty, the Mongols introduced these types of weapons into their own arsenal.

Warfare in the Mongol steppes had no use for artillery or siege equipment. The expansion into China was facilitated by defecting Chinese military engineers who brought with them the knowledge to build catapults and other forms of artillery, enabling the Mongols to breach the defenses of Chinese walled cities. With them, they launched not only stone, but oftentimes incendiary bombs (Haw, pp. 460-461). The latter method is how the Mongols were able to overpower Ryazan, the first Russian city they came into contact with, in just five days.

Russian towns and cities around the year 1237 were constructed mainly from wood, minus the churches, which were made from stone. This made Russian towns vulnerable to the fire-throwing catapults of the Mongol army (Haw, pp. 460-461). Another factor that may have aided the success of Mongol expansion in Russia was the weather—the attacks taking place in winter meant that it was nearly impossible to locate flowing water to extinguish the fires (Haw, pp. 460-461). After capturing Ryazan, the Mongols kept venturing westward until they reached Kyiv in present-day Ukraine. At the time, it was one of the biggest cities in Europe—the Mongols were able to capture it within twelve days.

Psychological Warfare

In addition to their increasing military arsenal, the Mongols were also known for employing elements of psychological warfare to create a cult of fear surrounding their image, driving intimidation into the opponents and victims of their armies. As mentioned previously in this article, there was a divine element motivating Genghis Khan’s conquests—he believed he was chosen by God to consolidate the world under a singular leadership.

It followed that as God’s messenger, he was sent to punish societies who had ‘sinned.’ Whatever societies collapsed under the weight of Mongol attacks was an implication they had done something wrong—Genghis Khan has been famously quoted as stating “I am the punishment of God” (Smojver, 39), and societies who were attacked or invaded by the Mongols saw it as divine punishment for sinful behavior.

Another element of psychological warfare employed by the Mongol armies included carrying out acts of cruelty in front of witnesses. In battle, this could be in the form of leaving one or two soldiers alive in order to spread the word of their destruction. However, soldiers weren’t the only targets of cruel spectacle—mass looting, sexual assaults, and the destruction of relics all took place in front of civilians of the societies they encountered. In one case, they deposited piles of corpses onto the banks of the Danube River (Smojver, p. 40).

While the Mongols were willing to grant considerable autonomy to cities and societies who willingly submitted to them, the fate of those who took up arms in response was often an unhappy one. Defeated enemy rulers who were taken captive would be executed, and their heads placed on public display to force the submission of their subjects. This was the fate of the unfortunate High Duke of Poland, Henry II, after the Battle of Legnica in 1241 (Smojver, p. 43).

In other cases, mass-killing campaigns took place that allegedly made “the whole earth…stained with red blood” (Smojver, p. 41). In Nishapur Persia, for example, because its people put up such resistance to the Mongols, after they captured the city, they ordered the entire population to be killed, even the city’s cats and dogs. This was all under the guise that God was allowing these actions to be carried out as it was their duty to act on behalf of God’s will.

Recruitment and Taxation

Following their conquests, the Mongols would conduct censuses to assess the military and economic capacity of their new subjects. This was how the nomadic Mongols could administer sedentary societies (Bayarsaikhan, p. 100). It was important for the Mongols to graft themselves onto the pre-existing political and social structures. The census would be performed by officials referred to as darughachis, who were the assigned governors for each region. These were typically selected military leaders left behind after conquests who functioned as mediators between the Mongols and local populations.

The first census of a town or city was to take note of the male population in order to enlist them into the Mongol armies. Two out of every ten men needed to serve (Bayarsaikhan, p. 107). After all the men were accounted for, a census would be taken for women and children. The purpose of the census was not just to document the people within a society, but also their skills, such as artisans. The census was crucial to the Mongols ability to not just conquer, but also to help them efficiently incorporate new lands and societies into their social, economic, and political framework.

Lastly, the tax system was an administrative element that strongly shaped the Mongol empire. There were three major taxes that were employed. Taghar was a tax on food to support the army, qubchur was a herd tax, and finally qalan, which was a tribute paid for soldier recruitment. The names of these taxes would differ per region, however their structures remained the same, and they would be carried out by the darughachi (Bayarsaikhan, p. 113). Although the tax system was structured on a local and empire-wide level, there would be some exceptions.

Darqan jarliqs were documents granting tax exemptions to certain religious institutions and people. Who exactly would be granted these exemptions was a bit complex and oftentimes differed per region and Mongol ruler, but initially exemptions were granted to certain mosques, churches, Buddhist monasteries, and Daoist temples. This would later include Jewish and Confucian leaders, and synagogues and temples, respectively.

Administrative Efficiency

The Mongols were a highly efficient military empire whose successes were enhanced by their policies of absorption. The Mongols not only made use of military technology from conquered realms, but also employed talented officials as administrators. One of Genghis Khan’s most influential advisors was Yelü Chucai, a member of the Khitan Liao dynasty who joined the Mongols in 1218 following the Mongol invasion of the Jin Empire.

The adoption of technologies and employment personnel from newly-conquered societies such as China and Persia may have contributed to the speed and force with which the Mongols reached Europe in the early 13th century. Further, the Mongols quickly became known not just for their military tactics, but the great violence and cruelty they often exerted on opponents.

However, the cult of fear created by the Mongols gave way to a highly-structured empire that incorporated all elements of the pre-existing societies into their social and political system. All members of society were accounted for, as well as their skills, in order to make the newly-evolving Mongolian empire one of the most efficient land empires in history.

However, the adoption of local customs also contributed to internal tensions between Mongol conservatives and reformers, the fragmentation of the Mongol empire into four parts in the late 13th century, which in turn led to the collapse of Mongol rule in the 14th century.

Bibliography

Bayarsaikhan, Dashdondog. (2011). Mongol Administration in Greater Armenia (1243–1275). In The Mongols and the Armenians (1220-1335) (Vol. 24, pp. 99–120). BRILL. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004192119_006

Haw, S. G. (2013). The Mongol Empire – the first ‘gunpowder empire’? Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 23(3), 441–469. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1356186313000369

Smojver, Domagoj. “Special Military Tactics Employed By The Mongols During Their 13th Century Conquest.” Polemos 25, no. 2 (December 28, 2022): 37–53.