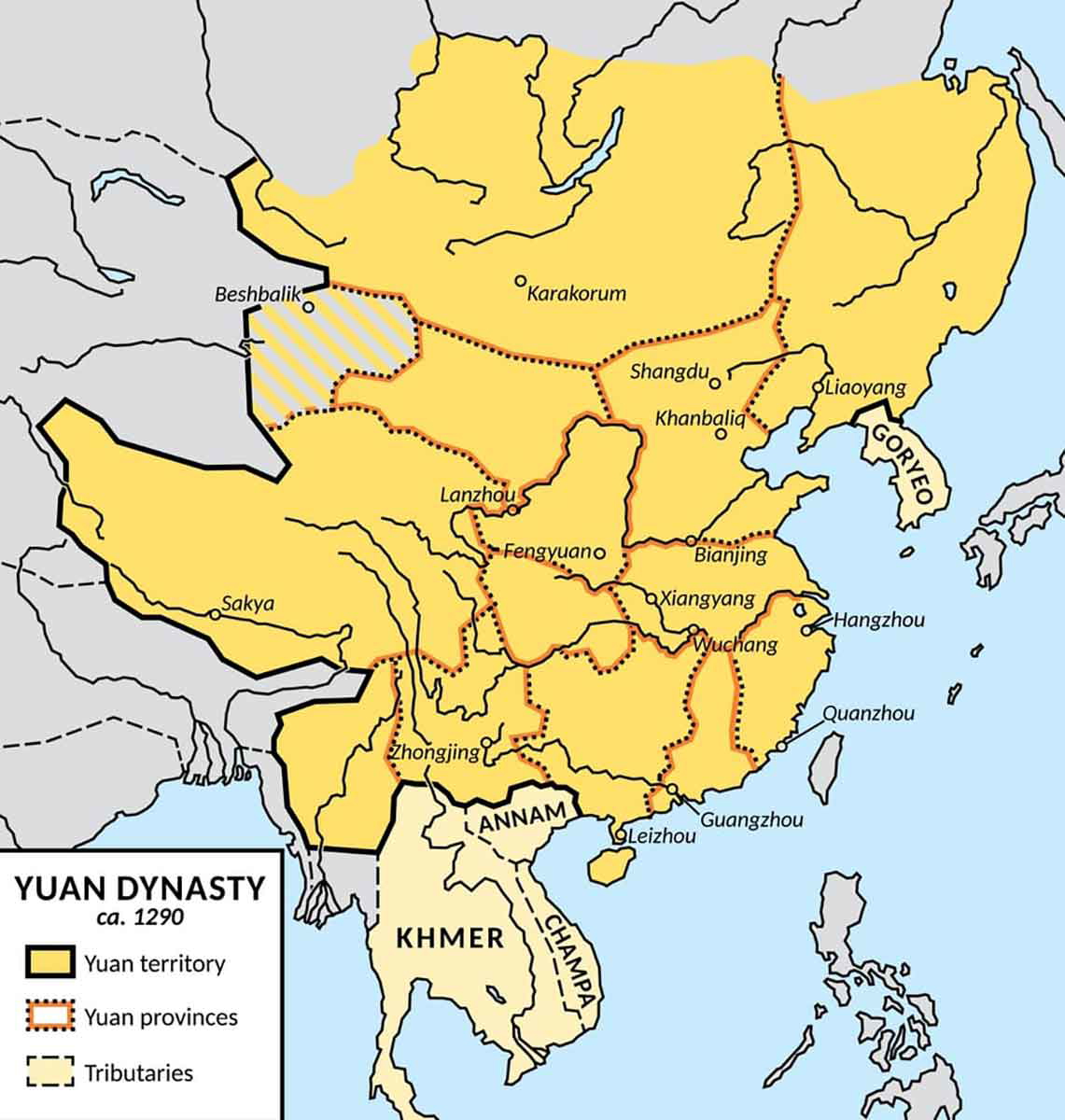

The Mongols conquered the largest land empire in recorded history. Their realm stretched across the Asian continent from China all the way to present-day Russia, Poland, Hungary, and the Balkans in Europe before declining in the mid-14th century. They are known today for their military capabilities and swiftness with which they defeated their competitors, oftentimes overpowering centuries-old empires. However, in the case of Japan, they were not so lucky. What happened? The story of the Mongols’ two failed attempts at invading Japan involves politics, naval warfare, and divine winds.

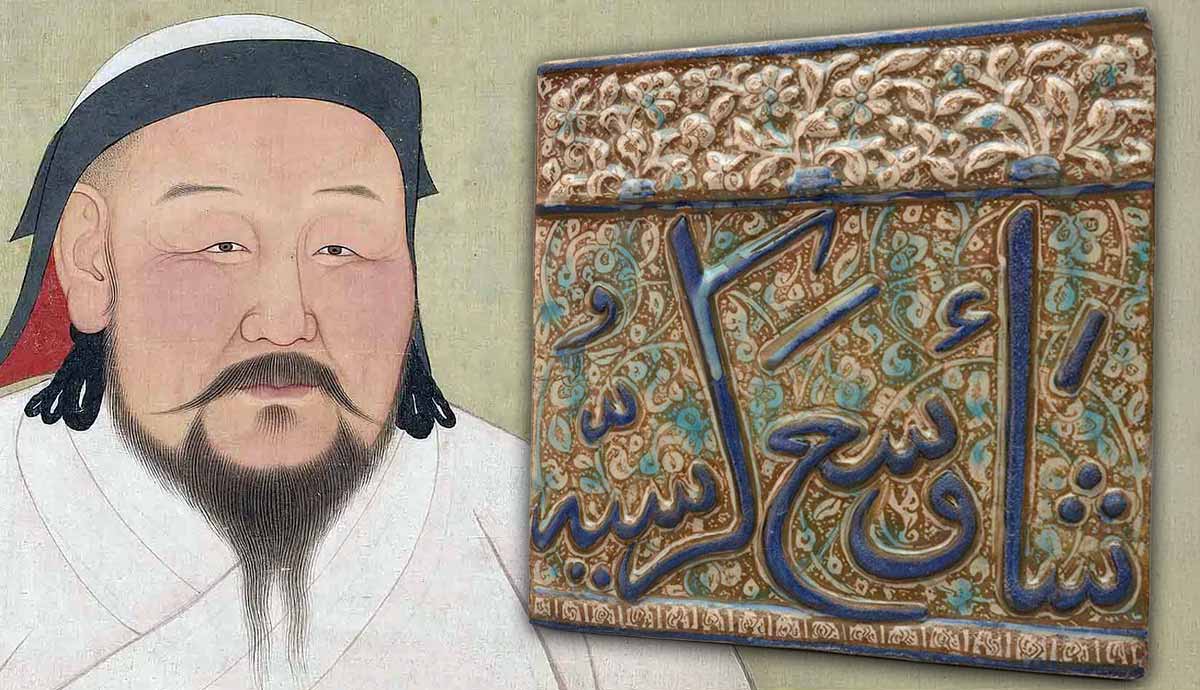

Kublai Khan—Genghis Khan’s Grandson

By the late 13th century, the Mongol empire in East Asia was being led by Kublai Khan, grandson of the first Mongol leader Genghis Khan. Genghis Khan’s original name was Temüjin, meaning ‘blacksmith’ or ‘of iron,’ before being changed to ‘Genghis Khan,’ a title which meant ‘universal ruler.’

Although the separate Mongol tribes across Central Asia were united under Genghis, the new empire became divided into four separate regions in the decades after his death in 1227. Each region was led by one of his sons and eventually their descendants. Kublai Khan was the son of Tolui, the youngest son of Genghis Khan, who was assigned to the land of Eastern Mongolia.

Kublai Khan continued Tolui’s territorial legacy by continuing Mongol expansion and power in East Asia. Like his grandfather, Kublai was a strategic military leader, and would eventually name his part of the Mongol empire the Yuan, or ‘origin of the universe.’ This is the empire Marco Polo would come into contact with during his travels to China, even meeting with Kublai Khan himself in 1275. This meeting blossomed into a 17-year relationship, during which Marco Polo served as a personal diplomat for Kublai Khan in his royal court.

An Unstoppable Object Meets an Unmovable Force- Diplomacy Between Kublai and Bakufu

Before the arrival of Marco Polo and the subjugation of China under Kublai Khan, however, the Mongol leader also had his eye set on a territory east of Korea: present-day Japan. There are many theories as to why Kublai Khan wanted to conquer Japan. Some scholars theorize that expansion into Japan was Kublai’s desire to increase Mongol power and territory, like Kublai’s grandfather Genghis Khan.

Japan was abundant with resources such as gold, silver, iron ore, and other minerals. Additionally, they were equipped with a strong military force. Samurais, meaning “ones who serve,” were high up in the hierarchical caste system of feudal Japan. The fighting capabilities of the samurai, who began training in childhood and were expert archers and swordsmen, could have made Kublai’s army unstoppable.

Both these factors would have been appealing to Kublai. Some historians, however, argue that the invasion of Japan, at least initially, was part of a military strategy to weaken southern China, at that time under the Southern Song Dynasty (Sasaki, p. 27). Kublai perceived Japan as the lifeline keeping the Southern Song afloat, at least, economically. This point will be explored in more detail below. In order to fully take over the Song, Kublai needed to sever its relationship with Japan.

Kublai sent an ambassador to Japan in 1266 to extend a diplomatic olive branch which was covered in thorns. What Kublai demanded was recognition of his power and tribute to be paid to his empire. This approach was typical of the Mongols; they encountered new territories by offering their absorption into the Mongol empire on the condition the region provide them with tribute. In the case of refusal, the Mongols would turn to warfare.

Japan at the time was being ruled by the Kamakura Bakufu or shogunate, a regime in which the emperor was effectively a puppet of the shogun or commander-in-chief. After a lack of response from the shogun, Kublai abandoned his diplomatic efforts and began military preparations. Kublai during that time continued to expand his territory, eventually gaining control over Korea in 1273. Before letting his new subjects catch their breath, he demanded an extensive fleet of ships to be built in order to attack Japan.

Although the Mongols were skilled at fighting on land, they were heavily reliant on the newly subjected Koreans and Chinese for maritime knowledge. Much of the manpower used to build and sail these ships was supplied by the Koreans and Chinese, who may have also taught Mongol soldiers. By the summer of 1274, a fleet of 900 ships were ready to be launched from Korea to head towards Hakata Bay in Japan.

The Invasion of 1274

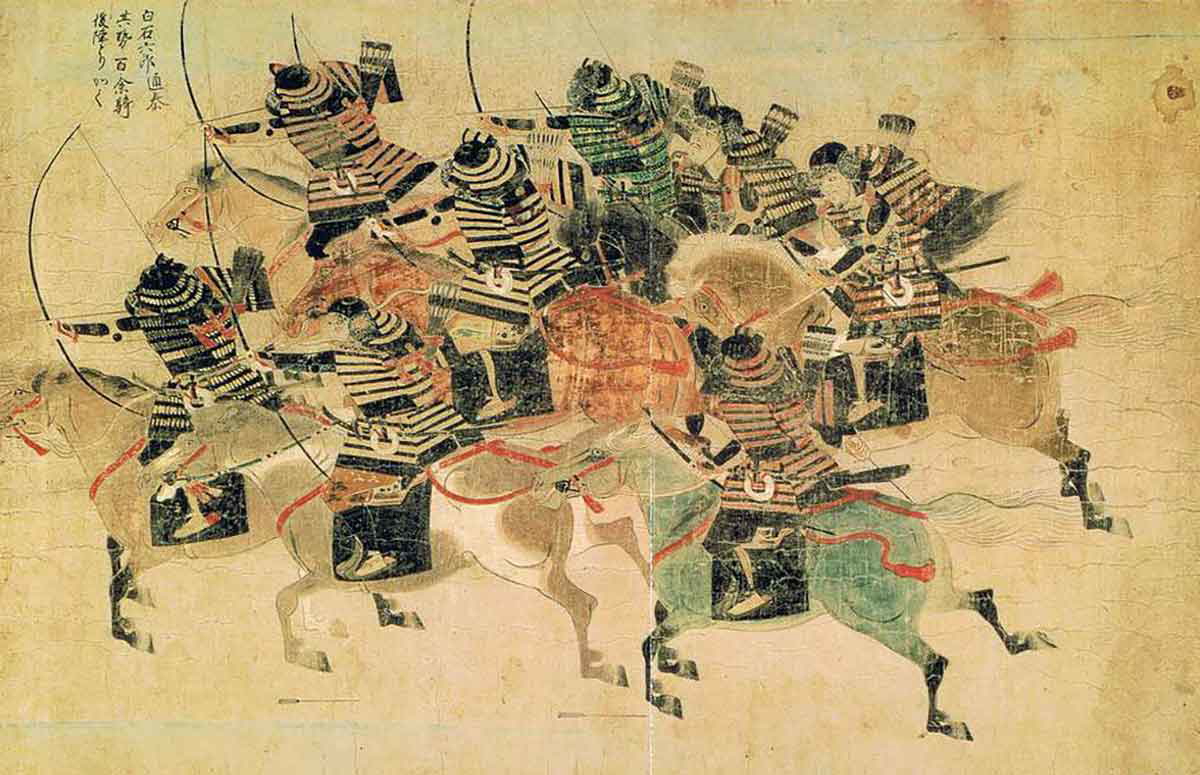

When the Mongol fleet left the ports of Korea, they took over the islands of Tsushima and Iki before arriving in Hakata Bay on the Japanese island of Kyūshū, in present-day Fukuoka City. Upon their arrival, they were met by Japanese soldiers led by Kikuchi Takefusa, a member of the Kikuchi clan, an important samurai group.

Mongol military tactics and technology were new to the Japanese soldiers. The samurai were taken by surprise by the group fighting tactics used by the Mongols. Additionally, the Mongols had a type of weapon they had yet to encounter—the exploding iron bomb.

The use of gunpowder to make bombs existed in China prior to the Mongols as early as the 11th century, and were even used against the Mongols by the Song military. This technology not only caused physical damage, but the loud bang it produced was also extremely disorienting for soldiers and horses alike. One can only imagine the chaos of sounds that erupted during this conflict.

This chaos is depicted in the Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba, or Illustrated Scrolls of the Mongol Invasion, which were commissioned by samurai Takezaki Suenaga, who fought against both invasions. Nonetheless, the samurai still were able to force the Mongols to retreat, splitting them into two groups who reconvened at Sohara in north-western Fukuoka.

The fighting continued in the bay until the Japanese retreated inland to Mizuki. Japanese soldiers waited there for an attack by the Mongols that never came. The Mongols burned Hakata to the ground, including the Shinto shrines of Sumiyoshi and Hakozaki, but instead of moving inland, left Hakata the next day. Although this first attack on Japan by the Mongols has been written off as Mongol failure, it may not have been intended to fully subject Japan.

The initial Mongol attack on Japan could have been intended to weaken the trading link between Japan and China. This is because Hakata Bay was the port that supported the maritime trade between Japan and the Southern Song. This trade helped the Southern Song finance their military expenditure—if the Mongols could break the trade route, they could undermine Kublai’s primary target. By disrupting trade links, the Mongols secured their strategic objectives without any need for further action.

The Second Attack and the Kamikaze

If the intention of Kublai Khan was to weaken the Southern Song, he succeeded. Southern Song fell to Kublai in 1279 and southern China was officially absorbed into the Yuan Dynasty. However, if Kublai’s intention was to weaken the Southern Song, why did he decide to attack Japan a second time? If there really was a storm that weakened the Mongol fleets, perhaps Kublai Khan perceived the invasion of Japan as an unfinished feat. Perhaps, now armed with the strength and numbers of the Southern Song military, he felt fully confident in a positive outcome for attack.

It should be noted that again Kublai sent a second ambassador to Japan in 1275. Allegedly, the response by the Kamakura was to behead the envoy. Such an action violated diplomatic norms and would have been cause for war, though the exact reason why Kublai decided to attack Japan a second time has been lost in the sands of time. However, what we do know is that an even greater number of vessels and soldiers accompanied this second attempt.

After his conquest of Southern Song, Kublai now had access to an extensive maritime fleet, and double the number of soldiers. Kublai prepared another attack on Japan in 1281, but this time, the number of ships totalled to around 4,400. Kublai also pursued a different strategy for the second invasion—instead of a single attack, Kublai organized two separate fleets that would attack from different directions. However, this strategy could have been a massive mistake.

When the eastern fleet arrived from Korea at Iko Island, they were supposed to meet a fleet arriving from southern China. Instead, the admiral commanding the southern fleet got sick and had to be replaced, delaying the arrival of the southern fleet by a month. There are reports that the eastern fleet was running out of food and its soldiers were exhausted. Finally, the southern fleet arrived at Iko Island, and both fleets headed towards Hakata Bay.

Japan was prepared for a second attack by the Mongols, and spent the years between the first attack in 1274 and 1281 building a 20-kilometer or 12-mile stone wall to defend Hakata. Kublai’s fleets made it all the way to Imari Bay. After a few days of combat, a typhoon came that destroyed almost 90 percent of the ships. The typhoon mostly impacted the southern fleet, killing between 70,000 and 100,000 soldiers. Allegedly, the ones who survived turned to fighting each other in order to clamber aboard the remaining ships. The eastern fleet returned to Korea, making this event the last time Kublai would try to attack Japan.

Impacts

The second attack orchestrated by the Mongols in 1281 would have a lasting legacy on the culture and self-perception of the Japanese people. Japan referred to the arrival of the typhoon as a divine intervention from god, referring to it as the kamikaze, or ‘divine wind.’ This name would be adopted by Japanese fighter pilots in World War II, whose sacrifice in suicidal missions was perceived like the destructive winds of the 1281 typhoon. This divine intervention signified the superiority of the Japanese people.

Additionally, the ability to resist attacks on two separate occasions by a political and military force that overtook places like China and Baghdad reinforced this perceived military superiority. In the 21st century, the defeat of the Mongol invasions continues to be a source of Japanese collective memory and national pride. The bay of Hakata is even a tourist attraction, which could perhaps lead to larger questions about war-related tourism.

As for the impact on the Mongols, Japan would always remain a sore spot for Kublai Khan. He began plans for a third attack, but was convinced by his subordinates to abandon them. The attack of 1281 cost Kublai a fortune in terms of weapons and soldiers, and he may not have been able to afford a third invasion of Japan even if he wanted to.

Likewise, Kublai enjoyed limited success in his other ventures to invade various Southeast Asian states, and Mongol control of China began to deteriorate in the decades following his death in 1294. Mongol rule in China lasted until 1368, when the Yuan Dynasty was overthrown by the Ming Dynasty.

Sources cited:

Sasaki, R. J. (2015). The Origins of the Lost Fleet of the Mongol Empire. Texas A&M University Press.