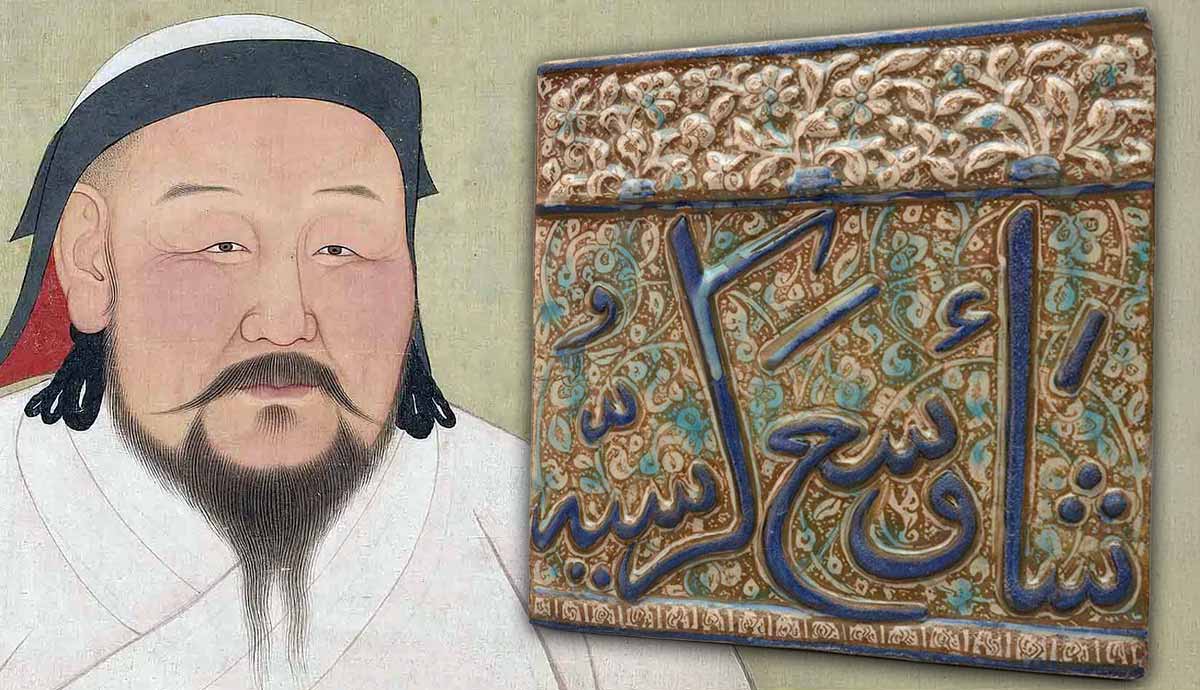

The Mongol Empire was a mosaic of different regions and religions that spread across the continent of Asia and parts of Eastern Europe. The Mongols today are most known for their brutality. In fact, Genghis Khan killed so many people that large areas of land were revitalized, removing 700 million tons of carbon from the earth’s atmosphere. In addition to Genghis Khan being the “greenest invader,” the Mongols were also known to be tolerant towards other religions. However, were the Mongols really religiously tolerant?

A Mosaic of Regions: The Mongolian Empire

The Mongol Empire expanded rapidly throughout Asia to Eastern Europe as a result of military conquest. Temüjin, who would become Genghis Khan, was the first to unify the different Mongolian tribes together. Under Genghis’ leadership, these newly unified tribes spread out across Asia from the Mongolian steppe, located between Russia and China. There was no single driver for the Mongol conquest, with economic, political, and religious factors all playing a role.

The harsh environmental conditions of Mongolia made the Mongols reliant on trade with other regions for resources. This trade, crucial to their livelihoods, was being threatened by the Jurchen Jin and Western Xia Dynasties in northern China, who began restricting how much the Mongols could trade with them. The desire to conquer Northern China could have been sparked by the necessity for survival.

Another factor for Mongol expansion could be attributed to Temüjin’s belief that Tengri, the Mongols’ principal sky god, gave him the mission to consolidate the entire world under the same sword. This could be the context underlying Temüjin’s renaming to Genghis Khan, or ‘universal ruler’ in 1206. Nonetheless, under Genghis Khan, the newly unified Mongol tribes spilled out from Mongolia, conquering northern China and expanding across Central Asia. Through territorial expansion, the Mongols were confronted with new religions and believers. How did they deal with these encounters?

Religious Tolerance or Religious Selectivity?

Although the Mongols have become understood as an empire that embraced religious tolerance, this may not have always been a part of Genghis Khan’s original policies and beliefs. In fact, ‘tolerance’ did not apply until his expansion into other territories. Thus, allowing believers to maintain their faiths was not integral to Mongol policy, but instead something that became increasingly incorporated and developed through interactions with other regions. Further, the ‘tolerance’ towards other religions outside of Mongolian Tengrism, a mix between shamanism and animism, was not applied to all religions, but only a select few. Thus, it may be a misnomer to label the Mongols as universally tolerant.

First Encounters: Genghis Khan and Buddhists

Although Genghis Khan came into contact with foreign religions prior to conquest, territorial expansion put him face to face with foreign clerics or religious leaders. The first he encountered were Buddhists. In 1214, Genghis Khan allegedly met Haiyun, a Zen Buddhist monk (Atwood, p. 244). Upon looking at the shaved head of Haiyun, Genghis asked him to grow it out and style it the Mongol way. This typically included shaved sides with the front grown out to form a braid. Haiyun informed him that doing so would make him lose status as a Buddhist monk. Genghis allowed him to keep his head shaven, a privilege eventually extended to other Buddhist monks.

Although this meeting could be fictionalized, it mirrors a second interaction that would take place some years later, again with Buddhist monks. This time, Genghis Khan and his armies arrived at a monastery at Mount Wutai in northeast China to conscript its monks into the Mongol armies. Yelü Chucai, the advisor for Genghis Khan, informed him Buddhists were strongly against killing, and doing so would be a severe transgression from their beliefs. Genghis listened to his advisor and left the monastery without conscripting the monks.

On both occasions, Genghis Khan, whose armies had decimated entire populations, left the Buddhists unbothered. Why?

‘This Kind of People’ and Several Pathways to God

The exemptions granted did not represent religious open-mindedness as we perceive in the 21st century. Instead, these exceptions were based on Genghis Khan’s own belief that these clergy were truly praying to ‘heaven,’ reflecting his own understanding about divinity, especially in regards to divine intervention.

Genghis believed that the divine power of a singular authority, God, was capable of intervening in the affairs of people on earth. This god responded to prayers, especially by those who were renowned for their spirituality, like monks or priests. His perception that Buddhists prayed to a single god aligned with this. Thus, to Genghis, both himself and Buddhists prayed to the same god. This god, he believed, was granting him success in his military ventures.

In addition to letting Buddhist monks keep shaved heads and avoid conscription, some were also made exempt from providing tribute and paying taxes. The decrees, referred to as darqan jarliqs, were granted to people and institutions Genghis believed truly prayed to heaven. The exemptions were conditional on the recipients praying for Genghis and his family (Atwood, p. 239). This is because “this kind of people” (Atwood, p. 245), needed to focus on their prayers that would continue Genghis Khan’s success. They could not be forced to pay taxes and tribute when Mongol victory depended on their spiritual labour.

During the time of Genghis Khan, darqan jarliqs were also applied to other institutions outside of Buddhism, such as certain Daoist temples and Muslim clergy, and specific people could be granted the title of darqan. For Genghis Khan, the specific religion didn’t matter; what mattered was that it fit into his belief system. He believed that “just as God has given the hand several fingers, so he has given mankind several paths” (Atwood, p. 252). Christianity (of which the Nestorian sect flourished in the East) was eventually added under Genghis’ third son and successor, Ögedei. Thus, as Buddhism, Daoism, Islam, and Christianity functioned based on prayer to a single authority, they were all under the umbrella of the god who supported the Mongols.

Exceptions to the Rule

However, prayer to a single god was not enough for Genghis Khan to grant exemption. These exemptions were not granted to entire religions but rather specific institutions or people. Genghis was also guided by other criteria that helped him determine if people were receiving blessings, or not, from God. Genghis believed God gave blessings in the form of prolonged life, or old age, or territorial control, political power, or economic success. For example, Qi Ghuji, a Buddhist monk who Genghis Khan allegedly met, was believed to be 300 years old. Moreover, the Pope was believed to be 500.

These are the reasons why Judaism and Confucianism were initially excluded in decrees during the time of Genghis Khan. During his reign, Jews didn’t have a stable state, and thus were not perceived as being blessed with political or territorial power. Notably however, they were still allowed to practice. Meanwhile, Genghis did not perceive Confucians as functioning based on prayer, and they were also excluded. Consequently, the allowance of religious groups to practice was not universal, but rather selective.

Historically, darqan jarliqs reflect this by granting exemptions to four religions—Buddhism, Daoism, Islam, and Christianity. Confucianism and Judaism were later additions in the Mongol Empire. Another reason different religious groups were able to continue their own religious practices was as a means to consolidate political control. While the Mongols enjoyed military superiority over subject peoples, there were not enough of them to take over the political administration. Accordingly, local elites who had submitted were often left in charge of their domains. In a similar vein, Yelü Chucai convinced Genghis that allowing newly conquered peoples to continue practising their faith would make his rule more readily acceptable (Atwood, p. 246).

Not All Mongols Were Tolerant

However, treatment of other religious groups during the Mongolian Empire was also contingent on the Mongol khan; the Mongols did not always grant even the ‘main’ four religions exceptions. In some instances, Mongol leaders tried to outlaw or restrict certain religions. Take for example Möngke Khan, the grandson son of Genghis Khan, who decreed the extermination of the Nizaris, an Isma’ili sect of the Shia branch of Islam. This is because Möngke was trying to establish the Il-khanate, the name given to the Mongol state in present-day Iran.

Kublai Khan, ruler of the Yuan Dynasty in Mongol China, was also prone to attacking other religions. In 1280, he made a command that targeted Islamic and Jewish dietary practices. The death penalty would be instituted for anyone who killed animals in the Islamic or Jewish fashion, which is done by slitting the throat in such a way no harm is caused to the animal. It is said that Kublai stated everyone under Mongol rule was required to “eat the food of our dynasty” (Atwood, p. 251). A refusal to do so was perceived as a sign of rebellion; Kublai considered all subjects under Mongol rule as his slaves.

The death penalty was also extended to anyone who performed circumcisions, another attack on Islam and Judaism. Kublai also targeted East Asian religions. He placed a restriction on Daoist writings, forbidding all except the Daodejing (or Tao Te Ching). Additionally, he wasn’t as generous with darqan jarliqs as other rulers—rather than granting new exemptions, instead, he ordered some religious institutions to pay taxes.

Converts

Certain Mongol leaders not only permitted other religious groups to practice their faith, but converted to it themselves. This was the case especially with Mongol groups in western Asia, who gradually became Muslims. Ghazan Khan, the seventh ruler of the Il-Khanate in Iran, converted to Islam in 1295, while the khans of the Golden Horde in Russia officially adopted Islam in the early 14th century. Although conversion sometimes served a political purpose, in some cases, such as Ghazan Khan’s, it reflected a genuine interest in the faith. In east Asia, Kublai Khan also converted to Tibetan Buddhism. In cases of religious conversion by the Mongols, sometimes Mongol Tengrism was not completely abandoned, but would become absorbed into the new religion.

Toleration With Limitations

Although the idea that the Mongols could represent an empire that was severely brutal at the same time as being religiously tolerant is an appealing paradox, this notion may not have existed for the reasons we would expect, and hope, it to be. While the Mongol Empire was cosmopolitan and culturally and religiously diverse in many respects, its religious policies fell considerably short of the concepts of freedom of worship and religious toleration as they are understood in the 21st century.

The selective permission of certain religious groups to practice their faiths under the Mongols reflected their own spiritual beliefs and political systems rather than a universal acceptance of freedom of religion. Nevertheless, non-Mongol religions were still practised in the empire, and some of their institutions and religious leaders were protected during the period of Mongol rule.

Sources:

Atwood, Christopher P. “Validation by Holiness or Sovereignty: Religious Toleration as Political Theology in the Mongol World Empire of the Thirteenth Century.” The International History Review 26, no. 2 (June 2004): 237–56.