Nathan Bedford Forrest is one of the most controversial figures from the Civil War Era. He was a self-made millionaire who made a fortune from the slave trade. During the war, he earned a reputation as an aggressive and successful cavalry commander. However, his actions before the war, at the Fort Pillow Massacre, and as the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan showed a dark side to him. Later in life, he tried to recreate his image. These actions have left his legacy to be debated even today.

Early Life

Nathan Bedford Forrest was born in 1821 in Chapel Hill, Tennessee. He was one of twelve children, and like many families living on the edge of the frontier, they had very little. His father died when he was just a teenager, leaving Forrest as the man of the house. With little formal education, he stepped up to support his mother and siblings learning the trade of blacksmithing.

It did not take long for Forrest to realize he had a natural talent for business and negotiation. Over time, he used that instinct to build a modest fortune buying and selling horses and land. Later, he expanded into cash crops such as cotton and eventually the slave trade. These businesses led Forrest to go from poverty to one of the richest men in the South during the Antebellum Era.

Moving to Hernando, Mississippi, in 1841, 15 miles south of Memphis, Tennessee, Forrest went into business with his uncle Jonathan Forrest. The venture did not last long as the elder Forrest was killed in 1845 by rival business associates, the Matlock Brothers. Forrest, filled with anger over the event, sought retribution, going after the brothers, killing two and wounding a third. Instances such as the Matlock incident showcased the fire and tenacity within the future cavalry commander.

Gaining Wealth Through Slavery

After working his way up from poverty through various business ventures, Forrest turned to the slave trade, one of the most profitable industries in the antebellum South. By the 1850s, he was operating one of the largest slave markets in Memphis, Tennessee: Forrest Jones & Co.

His business didn’t just involve local trading. Forrest bought and sold African American men, women, and children across the Deep South, often setting up impromptu slave auctions in Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana.

Slave census records from the 1850s and 60s show he owned a dozen people personally. At a time when the average slave owner claimed on average one or two slaves, Forrest’s personal slave ownership would place him comfortably within the “slavocracy,” the elite slave owners of the Antebellum era. Forrest used this wealth to purchase land, property, and political influence.

A Rising Star

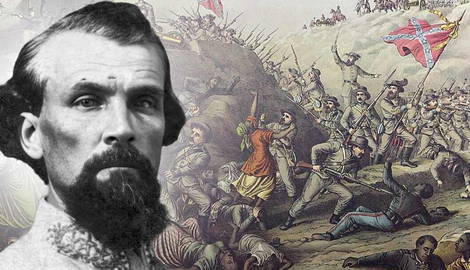

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, at a time when wealthy men North and South were using their influence to raise their own units in which they could serve as officers, Nathan Bedford Forrest enlisted as a private in the Confederate cavalry. It didn’t take long for his leadership to stand out. Without any formal military education, Forrest was promoted to lieutenant colonel within months.

At a time when the Confederate high command was inundated with graduates from West Point and veterans of the Mexican-American War, Forrest earned his promotions not through politics or connections, but through effectiveness in battle. He quickly gained a reputation as a fearless and aggressive commander, often leading his men directly into combat. His motto was simple: “Get there first with the most men.”

Forrest mastered the use of fast-moving cavalry raids, disrupting Union supply lines and communication routes. The aggressiveness of his strategy earned him the nickname “the wizard of the saddle,” but it also put him at great risk. Over the course of the war, Forrest would have 29 horses shot out from under him. His tactics were brutal but effective, leading to reverence in the South and fear in the North.

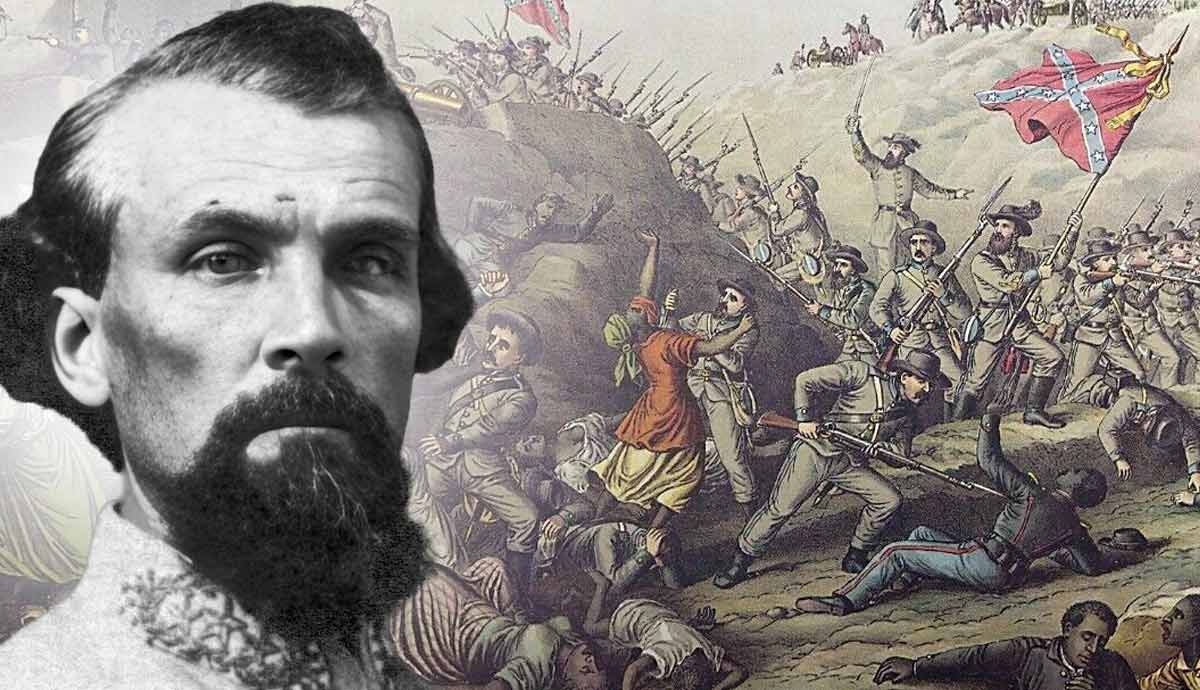

The Fort Pillow Massacre

One of the darkest chapters in the American Civil War came in 1864, during the Battle of Fort Pillow in Tennessee. The fort was occupied by Union troops, many of them African American soldiers from the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Forrest led a surprise assault on the fort, overwhelming the defenders in a swift and aggressive attack. What happened next remains one of the most debated events of the Civil War. According to Union reports and later investigations, many of the Black troops were killed even after they surrendered.

Eyewitnesses claimed that Forrest’s men continued to shoot unarmed soldiers yelling “No Quarter!” and refused to take prisoners. The Confederacy denied it was a massacre, insisting the fort’s defenders kept fighting after Forrest and his men demanded their surrender. But the sheer number of deaths—especially among Black troops—told a different story.

Of the roughly 300 African American soldiers stationed at Fort Pillow, nearly two-thirds were killed. The event sparked outrage in the North and became a rallying cry for Black Union soldiers and bolstered enlistment. Ulysses Grant, in his memoirs, commented on the event stating “Subsequently, Forrest made a report in which he left out the part which shocks humanity to read.” Whether Forrest gave the order or lost control of his men, Fort Pillow became a symbol of racial hatred and brutality.

KKK Membership

After the Civil War ended, Forrest returned to Tennessee. But the South was not the same. The end of slavery and the arrival of Reconstruction policies led to widespread resentment among former Confederates. In this climate, the Ku Klux Klan was born. Formed in Pulaski, Tennessee, in 1865 by former Confederate soldiers who wanted to strike fear within the newly emancipated African American community, it quickly became something far more dangerous.

Forrest was asked to lead the organization and became the first Grand Wizard of the KKK. Under his leadership, the Klan expanded rapidly and began using violence and intimidation to suppress Black political power in the South. Freedmen, along with white Republicans and allies, were targeted in night raids that often ended in beatings or lynchings. Forrest later claimed he disbanded the Klan when it grew too violent, but records indicate he remained secretly as its leader. Today, his name is forever tied to the KKK and will remain a part of his legacy forever.

Later Life

In the final years of his life, Nathan Bedford Forrest made efforts to change how people viewed him. After spending years as one of the South’s most feared and controversial figures, he began to soften his public image. He gave speeches calling for unity between Black and white Southerners and publicly denounced hatred and violence.

In 1875, when Forrest accepted an invitation to speak before an all-Black civil rights group in Memphis. There, he reportedly called for racial acceptance and even offered an apology for his past actions against African Americans. Some saw it as a genuine attempt to make peace. Others believed it was a political move, trying to save his reputation because the KKK had come under national scrutiny from the new Ulysses S. Grant administration, which had campaigned on disbanding the Klan. Forrest’s legacy remains complicated because of moments like this. Was he truly remorseful, or was it just an attempt to not be held accountable for the more vilest acts of his life?

Legacy

Few figures from American history divide opinion like Nathan Bedford Forrest. In the South, some view him as a hero for his efforts during the war. Streets and schools were named in his honor, and monuments to him were in various major cities for decades. But for others, especially African Americans, Forrest has long symbolized everything that continues to be a problem in the south today—racism, violence, and white supremacy.

In recent years, calls to remove his statues and rename public buildings have grown louder. Some cities, including his own town of Memphis in 2017, have taken steps to erase his public presence altogether, removing monuments and renaming streets and schools. However people choose to remember him, Nathan Bedford Forrest’s memory speaks to the unfinished business of American history.