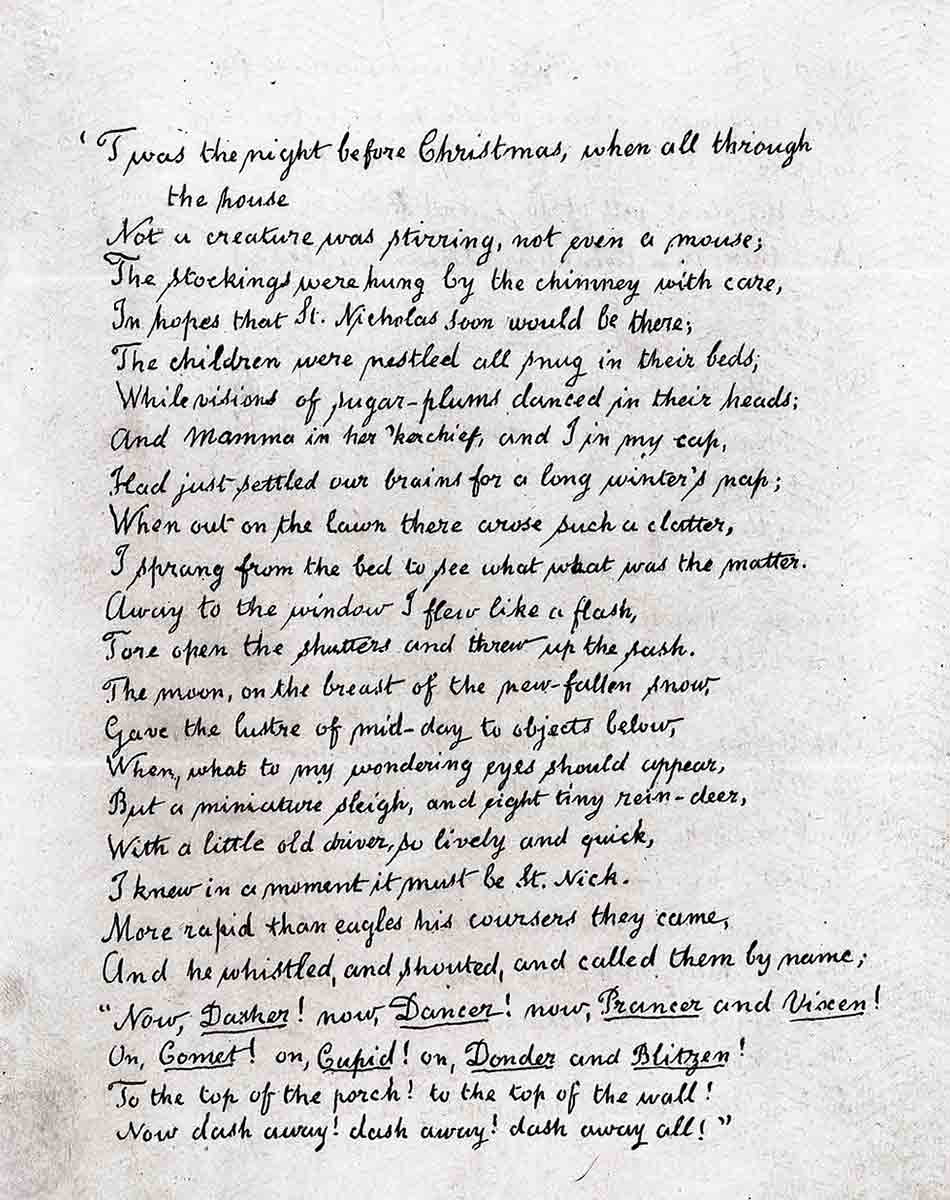

A Visit From St. Nicholas was first published anonymously in 1823. The poem is structured in rhyming couplets with an anapestic tetrameter, which regulates the stresses and creates a pleasing, gentle rhythm. In 51 lines, the tale gathers together centuries of folklore, European winter traditions, and local New York customs, distilling them into a vivid portrait of a visit from Santa on Christmas Eve. Its images contributed to the modern Father Christmas iconography we know today, featuring a jolly, white-bearded man in red fur-trimmed clothes, black boots, and a belt, carrying a gift sack, with a distinctive “ho ho ho” catchphrase. Long before this image was solidified into American visual culture by Coca-Cola, A Visit From St. Nicholas provided the Santa Claus blueprint.

A Tall Tale

The poem first appeared in the Troy Sentinel on December 23, 1823. It was signed off “Anonymous.” For decades, its authorship remained a mystery.

It arrived in an epoch where Christmas was still taking shape for Americans. Early 19th-century celebrations varied dramatically by region, and the figure of St. Nicholas was a patchwork of Dutch, British, and German traditions. This poem in the Troy Sentinel offered a coherent and totally charming image of Santa.

Years later, professor of Greek and Hebrew literature at General Theological Seminary, Clement Clarke Moore, came forward to claim authorship of the poem.

“some lines, describing a visit from St. Nicholas, which I wrote many years ago … not for publication, but to amuse my children.”

It was an unusual, but ultimately accepted, claim to the pen. But it wasn’t until 1837 that the poem would be published with Moore’s name attributed.

So, if Moore didn’t intend for it to be made public, how did it come to be published? The most widely shared version of events is as follows: Moore had written the poem on Christmas Eve 1822. At a New York City Christmas party hosted by the Moore family a few years later, Harriet Butler, a friend of the family, overheard Moore reciting a poem for the children of his guests. Butler was so amused by the poem that she asked Moore if she could copy it down to read to her own children. It is likely that this was then passed on and on between friends, uncredited to Moore. The following Christmas, a friend of Butler’s, Sarah Sackett, sent a copy of the poem to the Troy Sentinel, which published it anonymously.

As is to be expected, the poem was a hit with readers, and other local newspapers then began to reproduce the text for their own readerships. Akin to a viral TikTok video, the poem became a sensation and was soon circulated in national newspapers, Christmas booklets, and pamphlets.

However, it remained unattributed until Moore opened the Washington National Intelligencer one morning to see his own poem on the page. He released a statement of ownership and published A Visit From St Nicholas in a collection of poetry under his name that same year.

A Long Winter’s Nap

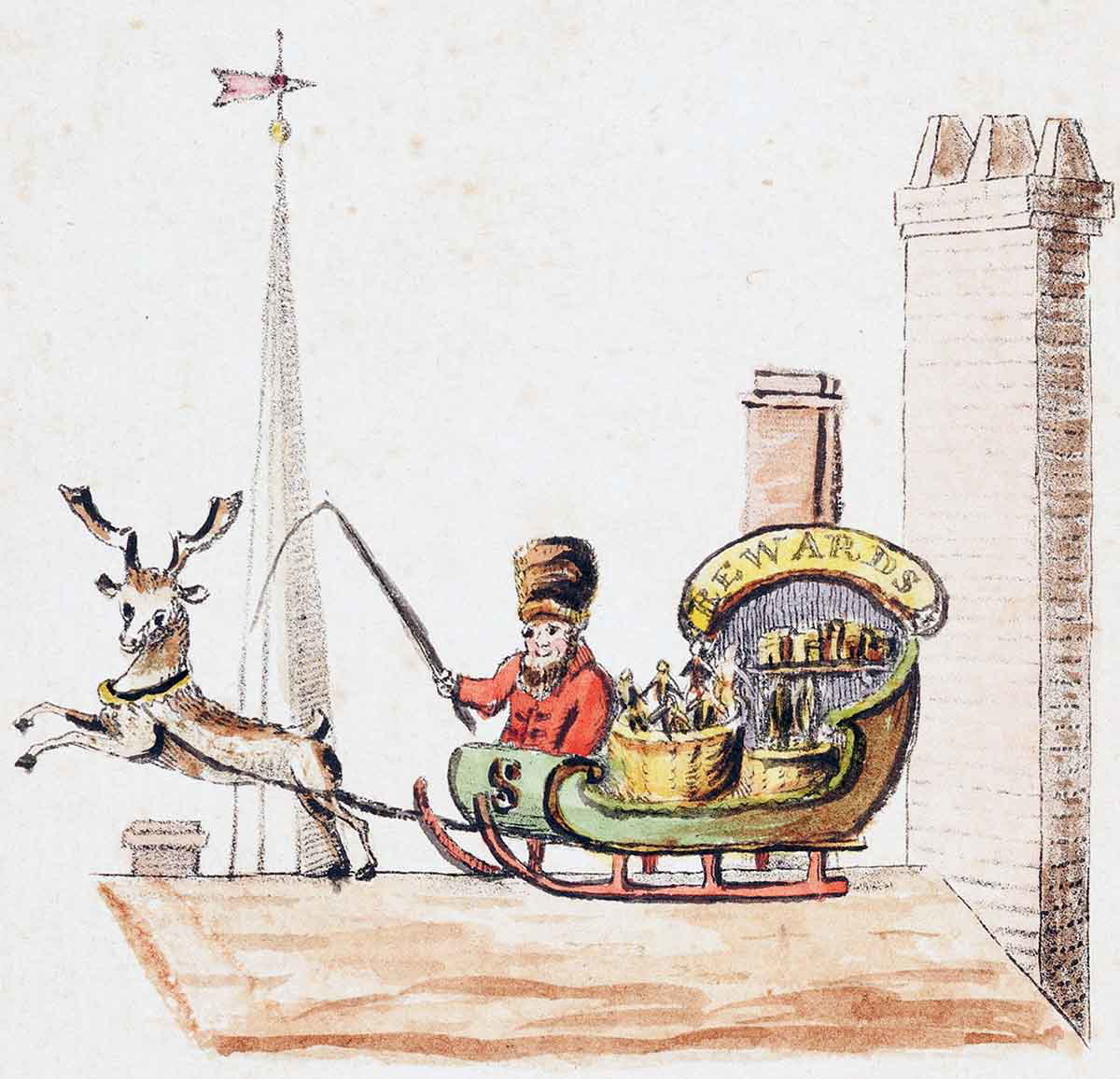

Before the poem’s publication, St. Nicholas was a visually inconsistent figure. To understand how revolutionary ’Twas the Night Before Christmas was, one must look at the figure of Santa before 1822.

Broadly speaking, St. Nicholas lacked a fixed definition; he was an undefined amalgam. In early America, St. Nicholas emerged from a composite of European traditions rooted in St. Nicholas of Myra, a saint known for generosity of spirit. Dutch settlers in New York brought over “Sinterklaas,” a tall, bishop-like figure in flowing robes who rewarded good children on December 6. British folklore included Father Christmas, a jolly but human-sized man often shown wearing green. German tales introduced “Pelznickel” or “Belsnickel,” a fur-clad, sometimes slightly fearsome visitor who struck terror into naughty children.

These early depictions were various, and therefore, there was no singular aesthetic. Some illustrations showed an ethereal and God-like winter bishop, while others preferred a rustic figure in a hooded cloak. As a result, no agreed-upon visual came to be. So, no reindeer, no sleigh, no chimney, and no universally recognized symbolism.

Clement Clarke Moore changed that. When “Down the chimney St. Nicholas came with a bound,” we meet Santa as we know him today:

“He had a broad face and a little round belly

That shook when he laughed, like a bowl full of jelly.

He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf,

And I laughed when I saw him, in spite of myself;

A wink of his eye and a twist of his head

Soon gave me to know I had nothing to dread;”

We learn that Moore’s version of Santa is benevolent, giving, and most importantly, harmless. Beyond that, his visual identity begins to take shape.

A Right Jolly Old Elf

By streamlining the various St. Nicks into a singular Santa Claus, Moore created an icon:

“His eyes—how they twinkled! his dimples, how merry!

His cheeks were like roses, his nose like a cherry!”

Attractive, kindly imagery draws a picture of an altruistic, pleasing figure. The physical sketch adds personality to the visuals by calling him a “jolly old elf” with a round belly, twinkling eyes, and fur-trimmed clothes. With this, Moore offers the first memorable physical blueprint. He shrinks Santa from a bishop or folkloric giant into a magically compact figure who can slip into homes undetected:

“He spoke not a word, but went straight to his work,

And filled all the stockings; then turned with a jerk,

And laying his finger aside of his nose,

And giving a nod, up the chimney he rose;”

Further, by giving Santa a purpose and an occupation, Moore instills further tangibility to a previously loose construct. Santa is given a sleigh, eight named reindeer, and a Christmas Eve schedule. In so doing, the poem replaces the patchwork of competing traditions with a character.

This was a cultural turning point. The poem transformed St. Nicholas from a solemn, moralizing figure into a warm, humorous, approachable presence. This was a character children could picture instantly.

But perhaps the poem’s most influential innovation was its naming of Santa’s reindeer:

“When what to my wondering eyes did appear,

But a miniature sleigh and eight tiny rein-deer,

With a little old driver so lively and quick,

I knew in a moment he must be St. Nick.

More rapid than eagles his coursers they came,

And he whistled, and shouted, and called them by name:

“Now, Dasher! now, Dancer! now Prancer and Vixen!

On, Comet! on, Cupid! on, Donder and Blitzen!

To the top of the porch! to the top of the wall!

Now dash away! dash away! dash away all!”

The names are rhythmic, dynamic, and memorable. Moore effectively canonized the reindeer team, giving future artists and storytellers a framework to build upon.

Visions of Sugarplums

Moore’s vision included a fixed date for Santa’s visit. The poem is staged on Christmas Eve, at the very moment of Santa’s arrival. While earlier traditions had gift-giving on December 6 for St. Nicholas’s day, Moore’s poem shifts the timeline to Christmas Day.

In moving the schedule and having Santa visit silently while households slept, the holiday was reframed forever. Christmas Eve is now a date of wonder and magic. The ritual of going to bed early, listening for sleigh bells, and waking to a stocking full of presents can still be traced to Moore’s influence.

While some European traditions already linked St. Nicholas with chimneys, ’Twas the Night Before Christmas made this detail universal. The poem’s depiction of Santa bounding down the chimney, emerging in a cloud of soot, and filling stockings hung “by the chimney with care” forms a narrative structure that still shapes Christmas illustrations today. While his apparent magical abilities would later inspire further imaginings and mythological expansions, such as Mrs Claus, the North Pole, and Santa’s elves, it is Santa’s essence as a benevolent and solitary nighttime visitor that emerges.

The poem’s imagery traveled quickly through lithographs, early Christmas cards, and magazines. By the late 1800s, illustrators like Thomas Nast of Harper’s Weekly picked up Moore’s details and expanded them, drawing Santa with fur-trimmed clothing and a toy workshop.

‘Twas the Night Before Christmas helped invent the version of Santa the world would adopt, and the entire visual tradition that followed relies on the poem as its foundation. 200 years after its publication, Moore’s lines are as popular as ever.