For much of our history, humans have sustained themselves through hunting and gathering wild plants and animals. However, our trajectory changed around 12,000 years ago when agriculture emerged as humans began to domesticate livestock and crops, permanently altering our landscape. The origins and driving forces of this shift have long been the subject of debate among researchers, particularly given the fundamental role of agriculture in shaping the development of human settlements and technological advancements.

The Neolithic Revolution

The “Neolithic Revolution,” coined by Gordon Childe in the 1930s, refers to the transition from hunting and gathering to farming. The concept highlights the revolutionary impact of agriculture on human society. The process led to a shift in our reliance on wild resources and ultimately changed the way we live. A series of “revolutions” occurred independently in several locations, originating in the Fertile Crescent, a region with rich soils that spans across several countries in the Middle East. However, many researchers have since criticized this theory. They challenge the timing and speed of the transition to agriculture, the idea that farming is superior to foraging, and the drivers that led to domestication and farming.

Rather than a rapid transition, as implied by the term “revolution,” the path to plant and animal domestication required a series of complex and gradual changes to the relationships between humans, plants, and animals. While the beginning of the Neolithic period, around 12,000 years ago, is associated with the advent of agriculture, it is important to recognize our history of developing hunting techniques and knowledge of plant life and growth cycles long predates this.

A common misconception about early farming communities is that the shift from hunting and gathering to agriculture saw an instant increase in food resources, life quality, and population size. Although people eventually grew to benefit from increased food production, early farmers were met with low returns and high risks. They often had to combine hunting and gathering with farming practices. Moreover, the shift to farming introduced new health challenges, including the spread of new diseases, poorer nutritional conditions, and the physical burdens of manual labor.

While sedentism, the practice of permanently settling, is heavily linked to agriculture, sedentary lifestyles arose long before the Neolithic period. Moreover, it was not a unidirectional transition. Many farming groups moved between sedentism and mobility. For instance, climatic changes in the Levant during the Late Natufian period, around 11,500-12,800 years ago, forced reversions back to a more mobile lifestyle. In contrast, Early Natufians exhibited signs of sedentism, such as stone architecture, heavy-duty tools, storage pits for surplus resources, cemeteries, and commensal species like mice.

The Drivers of Agriculture

Sporadic and independent attempts to modify and manage plants and animals occurred in several locations and at different times, eventually leading to domestication and the onset of agriculture. Early signs of agriculture are observed to have occurred when the ice sheets of the last ice age shifted and the Pleistocene Epoch, a period of time known for its glacial and interglacial climatic cycles, came to an end. Although global climate change played a role in agricultural development, this explanation alone cannot account for the timing of domestication.

Researchers have proposed several theories to explain what drove our ancestors to begin domesticating wild plants and animals when they did. These theories include internal factors that ignited our intrigue to adopt new practices and external stressors that forced our hand. One idea, known as the Optimal Foraging Theory, proposes that domestication was a survival response. Foragers will choose resources with delayed returns when high-ranking resources, such as larger game animals, are less abundant.

Opposingly, the Cultural Niche Construction framework argues that humans can modify their environment rather than simply adapt to it in a process called “niche construction.” Unlike the Optimal Foraging Theory, this approach argues that a stable and resource-abundant environment supports our commitment to the activities involved in the long-term process of domestication. Evidence generally indicates that foraging communities situated in river valleys had access to distinct habitats with varied and abundant food sources.

Human modification of the environment also appears to precede the onset of domestication. There is evidence of human-made fires causing the movement and increased availability of high-value animals and plants.

The Founding Crops

Even today, thousands of years later, we still benefit from the domestication of crops by our ancestors in different areas of the world. The modern human diet is composed of relatively few crops, with almost 70% of our calorie intake coming from just 15 crops, particularly rice, wheat, maize, sugarcane, and barley. These crops were domesticated around 11,000 years ago through artificial selection, which enhanced the suitability of wild plants to the requirements and preferences of humans.

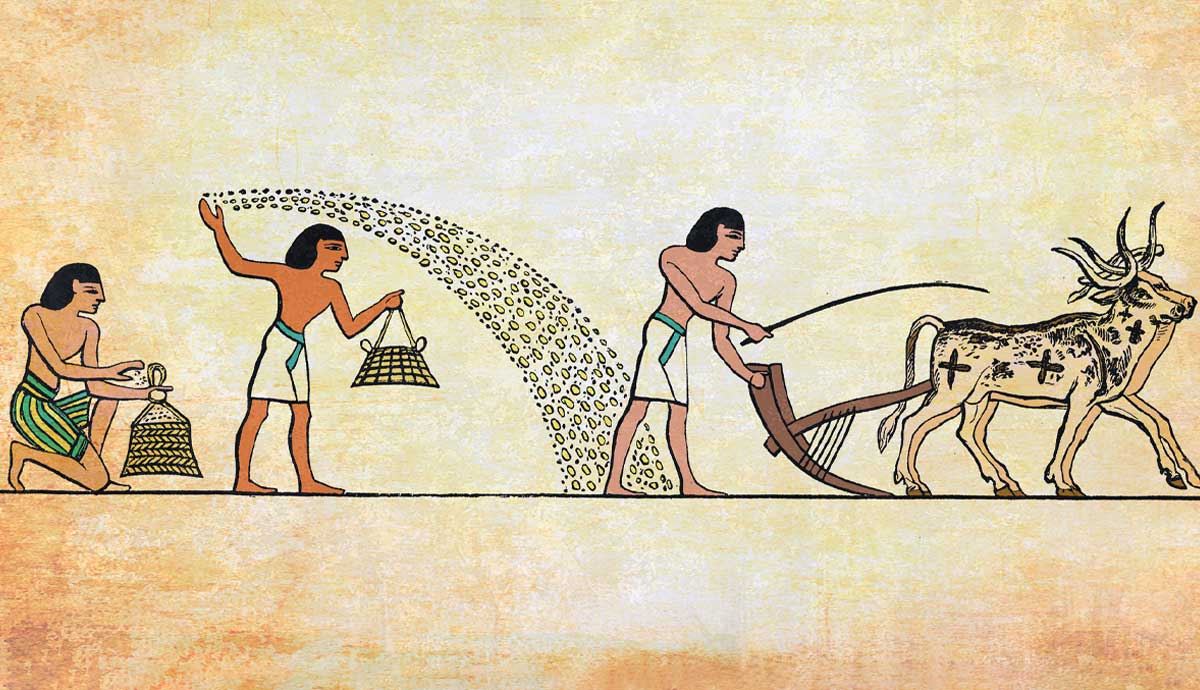

During domestication, both the plant and human benefit from a mutualistic relationship, as the farmer must meet the needs of the plant to benefit from high-quality and abundant crop yields. Rather than conscious choices, the early domestication of plants was largely driven by unconscious selection. Non-shattering cereal crops, for instance, are thought to have been selected as the result of sickle harvesting, which unintentionally favored non-shattering seeds that had not dispersed onto the ground when harvested. Traits such as non-shattering, loss of seed dispersal, and synchronous germination are believed to have been subject to unconscious selection, while traits like color and taste occurred through conscious selection by humans.

The first crops, including wheat, barley, peas, and lentils, were domesticated in Mesopotamia in the Fertile Crescent, between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Researchers have highlighted several other centers of domestication, including the domestication of crops like rice and millet in China, African rice in sub-Saharan Africa, maize in Mesoamerica, sunflower in Northeast America, potato and chili peppers in South America, and yam and banana in New Guinea. Over time, domesticated crops reached Europe from the Fertile Crescent, acquiring new crops and farming practices from other regions as they spread and adapted to diverse climates.

The Domestication of Animals

The dog was the first animal to be domesticated, originating from independent lineages of wolves in Europe and Asia over 15,000 years ago. They initially served as hunting companions. Goats and sheep, followed by pigs and cattle, were the first livestock in the Fertile Crescent, domesticated shortly after the first crops in the region. Over the next 10,000 years, the genetic makeup and observable traits of animals such as horses, camels, and chickens were altered as they adapted to human environments across different regions of the world.

Three pathways are described for domestication: commensal, prey, and directed. Animals such as dogs, cats, and chickens have followed the commensal pathway, in which a wild animal forms a commensal relationship with humans as they are attracted to food waste or prey animals associated with human settlements. Many significant livestock species, including sheep, goats, and cattle, were domesticated through the prey pathway, initially serving as prey animals hunted by humans for their meat. Hunters took advantage of certain characteristics displayed by herd species, such as adaptability to confinement, flexible diet, and fast growth, and began to practice management strategies that gradually led to captive breeding. The last pathway to domestication, the directed pathway, refers to the more intentional process of exploiting an animal’s resources, such as the use of donkeys, horses, and camels for transportation and carrying.

As communities migrated from the Fertile Crescent, they took with them livestock and farming techniques, which were adapted to new climates. Evidence of the lactose persistence phenotype, enabling adults to digest the lactose in milk, highlights the prominence of dairy farming that reached regions of Europe, particularly Finland. Many livestock are found to have domesticated independently in different regions of the world. Pigs, for example, were domesticated from wild boars at least twice, in the Fertile Crescent and East Asia.

The Consequences of Agriculture

Agriculture had a monumental effect on human history, enabling the immense population growth that ultimately led to complex societies with literature and architecture. However, this shift introduced new challenges. From human bone and tooth analysis, archaeologists found increased periods of malnutrition, tooth decay resulting from rising carbohydrate intake, and changes to bone shape due to the intense work involved in farming. A growing and increasingly sedentary population, with contained animals and rubbish, facilitated the conditions for a disease epidemic to emerge.

Emerging research suggests that the shift from labor-intensive farming to land-intensive farming using plow oxen enabled landowners to acquire more wealth. Wealth inequality is proposed to have occurred more prominently in Eurasia than in regions like the Americas, where domesticated draft animals were not available post-Neolithic. Surpluses of food resources allowed for the emergence of new roles, including religious and political leaders, and elites gained economic power through control of food surpluses. While social inequalities were likely to have predated agriculture, anthropologists often link the rise of agriculture with the rise of social hierarchies, higher levels of inequality, and more gendered labor division. Early agricultural societies were diverse, and many societies that adopted agriculture remained egalitarian for millennia.

The Cradle of Civilization

As populations and agricultural development grew, the earliest civilizations of complex societies with political hierarchies began to emerge, originating in Mesopotamia in the Fertile Crescent. Known as the “cradle of civilization,” Mesopotamia became the first civilization to flourish 6,000 years ago, benefiting from the fertile lands and regular flooding of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers.

As the rivers’ water levels were low during sowing and high before harvest, managing the water systems through irrigation systems was a necessary advancement for the region to adopt. A complex system of canals and waterworks was developed in Sumer, Mesopotamia, eventually leading to prominent city-states such as Uruk and Ur and the rise of empires like Babylonia.

The innovations of Mesopotamia influenced subsequent civilizations around the world, including advancements in architecture, law, mathematics, and the world’s first writing system—cuneiform. Across the globe, humans experimented with new crops and techniques, such as the terracing farming technique in the Andes mountains and the irrigation systems of the Yellow River in China. These advancements reflect human adaptability to changing environments and laid the foundations for the technology and societies of the modern world.