In the early 16th century, the Portuguese explorer Aleixo Garcia found himself with a unique opportunity: to join the indigenous Guarani in an expedition across the Peabiru path, from the south of Brazil to the capital city of the Inca Empire in the heart of the Andes. This pre-Columbian pathway of uncertain origin connected the various regions of South America and was used to exchange goods, culture, and ideas among the indigenous peoples.

Peabiru’s First European Traveler: Aleixo Garcia

At the end of a mission across southern South America, explorer Aleixo Garcia found himself stranded: a shipwreck had ruined his chance to travel back to his Portuguese homeland, so Garcia was forced to find new ways to survive. One possibility was to integrate with the locals. And so it was: for eight years, Garcia lived among the Guarani, one of the largest indigenous groups of the region, learning their language and customs. And before long, it was time for a brand-new adventure.

In 1524, the Portuguese explorer joined the Guarani on a mission across the Peabiru path, a 1,000 km (600 mi) journey westward into the interior portions of the sub-continent. Accompanied by an army of 2,000 indigenous warriors, Garcia traveled through the dense forests and rugged terrain of what are now Brazil and Paraguay, from the southeastern coast of South America all the way to the Andes mountains.

The expedition was driven by tales of a mysterious, rich land known for its wealth in gold and silver, related to the legends about the mythical El Dorado. But as fantastical as these lands sounded, they were far from fictional: these legends described what is today known as the Inca Empire.

A year after starting the mission, the group reached Cusco, the capital of the Incas. Although the Incas were waiting for the invaders with an army of 20,000 men, Garcia’s group was able to collect substantial quantities of silver and other valuables, confirming the legends of the rich lands to the west.

Peabiru: Ancient Travelway

The tale of Garcia’s remarkable expedition on the Peabiru pathway is one of exploration and ambition. But although the Portuguese explorer was the first European to penetrate deep into the interior of South America, many others had walked these steps before him.

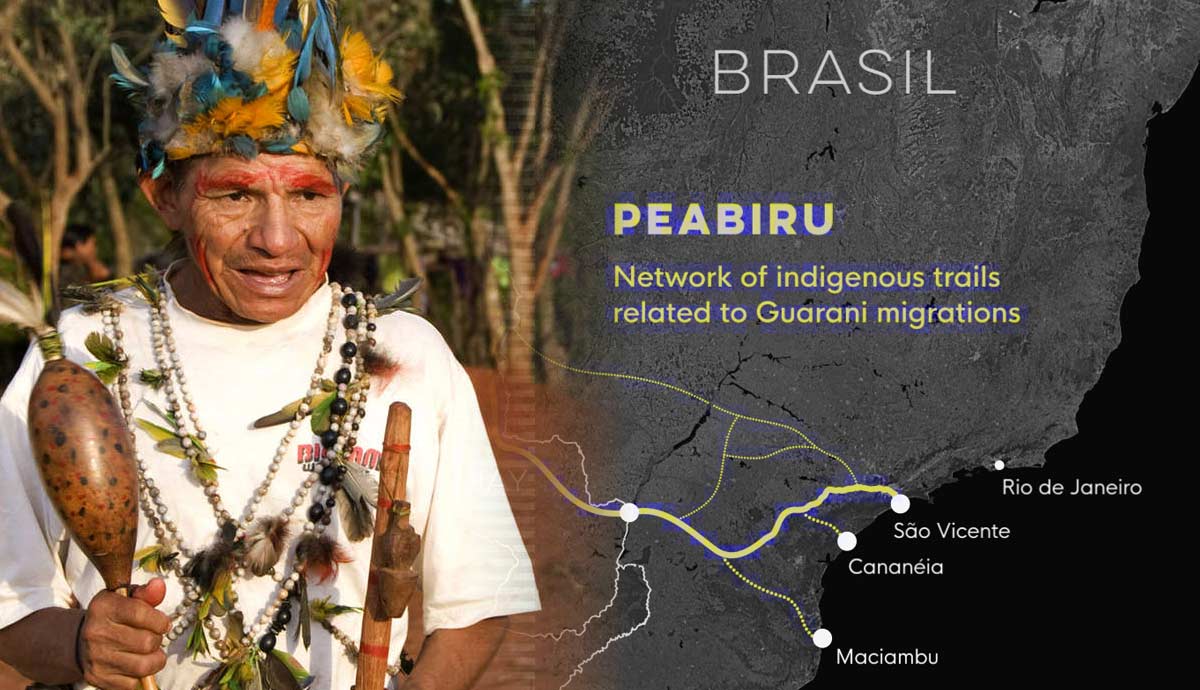

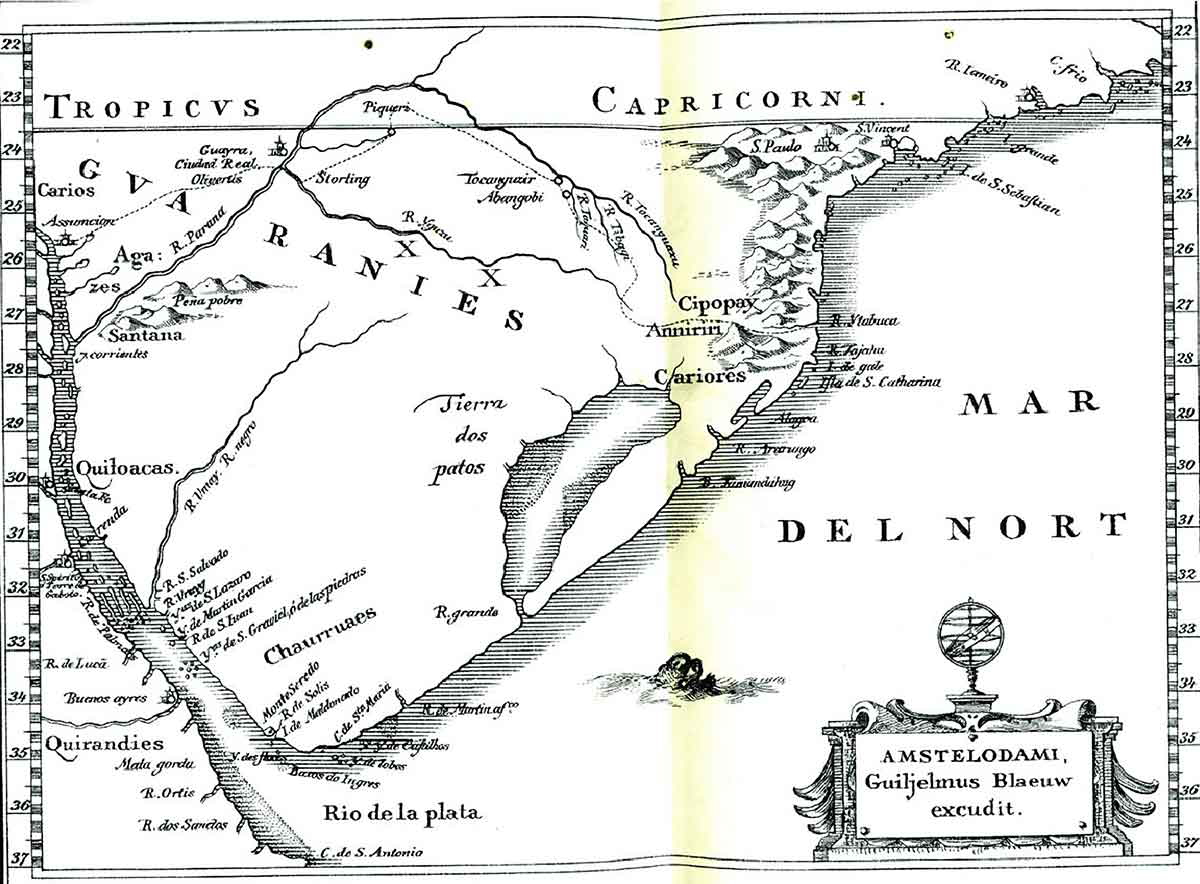

Linking the Atlantic coast of modern-day Brazil to the interior regions of South America, the Peabiru path is one of the gems of pre-Columbian history. The name of this 4,000-kilometer (2,500-mi) system of trails comes from the Tupi-Guarani language: “Peya Beyu,” meaning “crumpled grass path.” It first appeared in written sources in 1873 in Spanish Jesuit missionary and historian Pedro Lozano’s book History of the Conquest of Paraguay, River Plate, and Tucumán. However, the name seems to have been in use even earlier, dating to just after the arrival of Portuguese and Spanish sailors in Brazil in the 16th century.

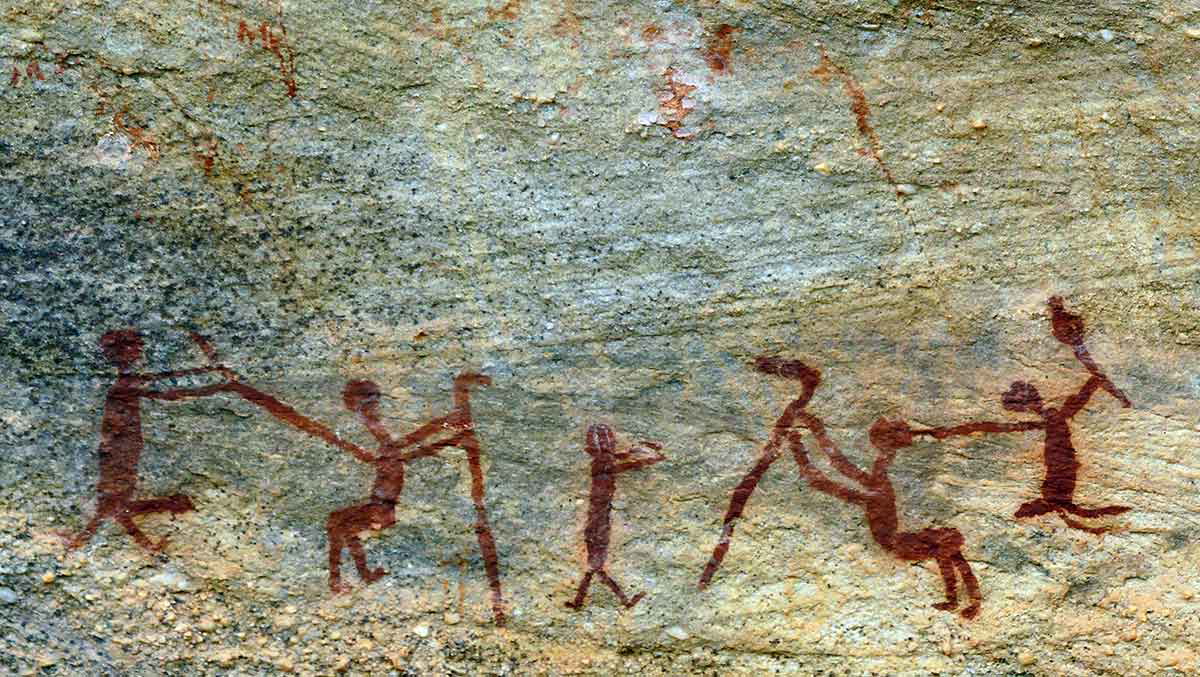

Although details about the pathway’s origin and extent remain a mystery, archaeologists agree that the Peabiru was widely known and used by many indigenous populations, including the Tupi, Guarani, and Inca civilizations. It was probably the largest of the ancient trail systems that connected the indigenous groups of pre-Columbian South America.

Its main road had three starting points along modern Brazil’s south and southeast Atlantic coast, corresponding to the present-day states of São Paulo, Paraná, and Santa Catarina. It then crossed the interior portion of the continent, passing through present-day Argentina, Paraguay, and Bolivia until it reached the Inca lands in the Andes. There, the Peabiru merged with the Qhapaq Nan, an Inca trail system of over 30,000 km (18,640 mi) recognized as a World Heritage Site in 2004.

The Peabiru is a testament to the sophisticated engineering and navigation skills of the indigenous peoples. Its construction, often through dense forests and across vast distances, showcases the ingenuity and skillfulness of these ancient communities. But as important as it was, the Peabiru was only one of the many trail systems that ran through South America.

Also worth highlighting are Araucanian paths, a system that connected the southern portion of present-day Chile and Argentina and allowed migration and trade between the different Mapuche peoples of the region. The Chachapoya paths in northern Peru connected the high-altitude settlements of the Andes, often located in remote and rugged areas. A series of land and river trade networks also cut through the dense rainforests of Amazonia and were used by groups such as the Tupi, Arawaj, and Carib.

Exploring the Peabiru’s Possible Origins

The exact origin of the pathway is still debated by archaeologists and historians. Some sources date it to 3,000 years ago, while others suggest a much earlier origin for the trail system. Archaeologist Claudia Inês Parellada, an expert on the history of the Peabiru, points to a possible link between these paths and the Paleo-Indian hunter-gatherers of 10,000 years ago. Her hypothesis suggests these ancient natives were the initial builders of trails that would later be incorporated into the Peabiru.

Theories from the 19th century support the hypothesis of an Inca origin, suggesting that the Peabiru was created to expand their empire to the Atlantic Ocean. Others defend the theory that the Guarani originally made the pathway to maintain contact with other indigenous groups and create a sort of mail system from the south of Brazil to Amazonia.

Peabiru in the Indigenous Mythos

While the natives left no written records detailing the use of the Peabiru, the trail system was undoubtedly central to their societies. Many of the chroniclers of the conquest describe how the pathway was used extensively for the interconnection of cultures and as a trade route. In particular, it served an important role for the Guarani, who used it to travel to the Inca Empire and bring some of its gold back to their own lands.

The route was not only used for trade and communication; there was a spiritual meaning attached to it as well. The Guarani placed the pathway within their mythic worldview, embedded in their search for the “Land with no Evil.” Following the sun’s path from east to west, the Peabiru could have been used to try to reach their sacred land. Guarani oral tradition also suggests that the distribution and shape of the trails within the Peabiru mirrored the Milkway—Moboré rapé, in their language.

Exploring the Indigenous perspective and interpretation regarding this pathway allows a better understanding of the intrinsic relationship between spirituality and everyday life for their communities, enhancing present-day knowledge regarding these mysterious paths.

Colonizing the Peabiru

Aleixo Garcia’s expedition on the Peabiru sparked Europe’s imagination regarding the possibilities that adventuring across South America could offer. In 1541, the Spanish explorer known as Cabeza de Vaca also sought out the support and guidance of the Guarani while seeking to explore the mythical pathway. Leaving from the region of the Itapocu River along the south of the Atlantic coast, he crossed the interior of the continent until reaching present-day Paraguay, where he was elected governor of the province.

The existence of the trail system also came to be known beyond Spain and Portugal. In 1552, Bavarian Ulrich Schmidl received guidance from Guaranis to reach the province of São Vicente, in present-day São Paulo, leaving from the city of Assunción, Paraguay. He detailed this six-month expedition in what became one of the most important written descriptions of the Peabiru, serving as a guide for other European explorers in the early days of South America’s colonization. Among the many details provided in his manuscript is a description of the bifurcation of the pathway on the East coast, where it divides between a route to the coast of Santa Catarina and a path that went all the way north to São Paulo.

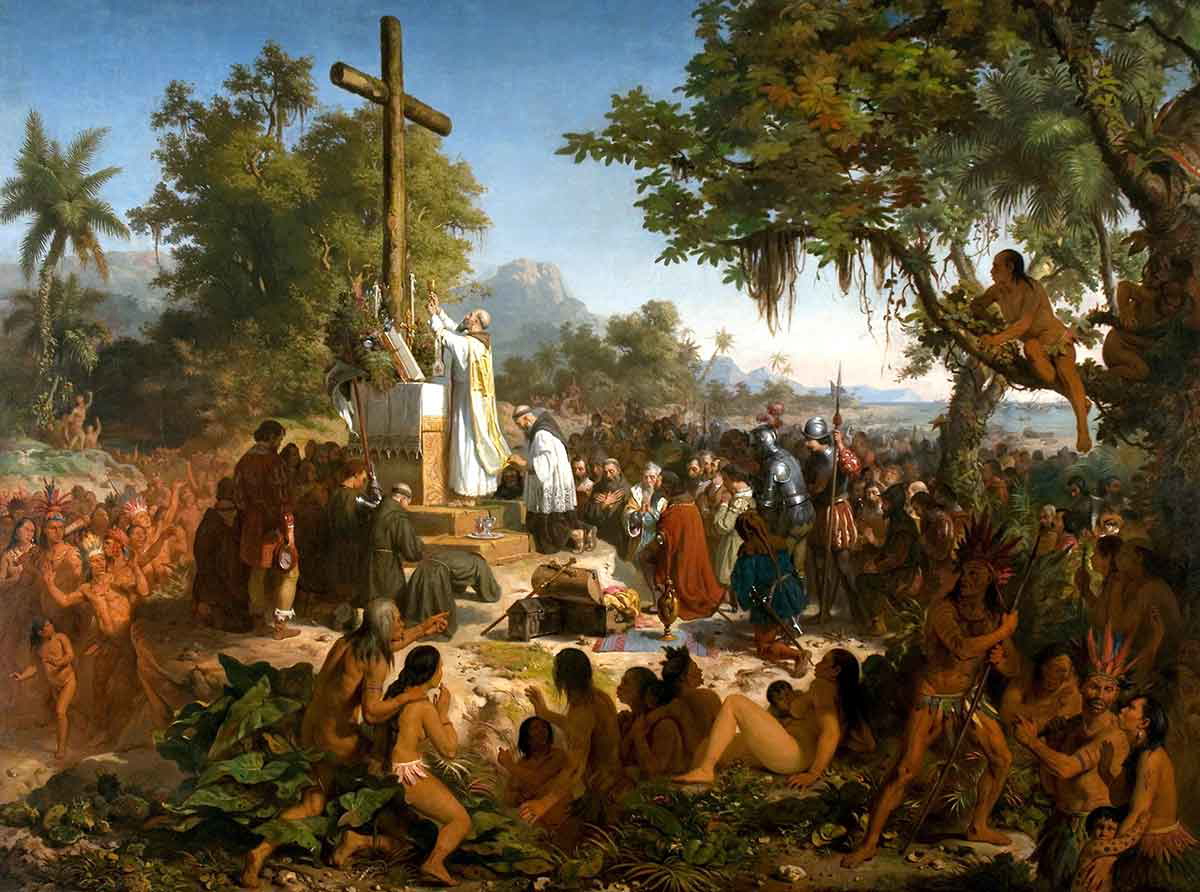

The path also played an essential role in the Christianization of the natives. Serving as a route for Jesuit missionaries of the early 17th century, the Peabiru was the only way into the interior parts of the continent that were inaccessible by sea. It was largely the exploration of these missionary priests, who also described the many alternative routes, that resulted in valuable historical sources for understanding this mysterious trail system.

The Peabiru Today

Identifying traces of the ancient pathway is challenging. Over the centuries, the construction of roads over the ancient routes and natural changes in the landscape have erased most of the trails. However, archaeologists have undertaken numerous efforts to preserve and study the remnants of the Peabiru that are still identifiable.

In 1970, archaeologists from the Federal University of Paraná identified around 30 kilometers (19 mi) of the trail system. They identified archaeological sites along the trail, with traces of dwellings used by indigenous peoples who traveled in the region. More recently, an initiative carried out by the Brazilian state of Paraná has been devoted to revitalizing the pathway. The so-called “Peabiru Project” aims to restore at least 1,550 out of the total 4,000 kilometers of the ancient road, creating a tourist attraction that will bring new visitors to the location and immerse them in the landscape of pre-colonial South America.

Some of the techniques applied in identifying the path involve analyzing historical sources and involving native communities. By providing their traditional and ancestral narratives, the indigenous are playing a central role in revitalizing the pathway, making the reconstruction even more accurate. Their participation also allows Indigenous voices to be at the forefront of historical research and heritage management, making them protagonists in their own history.

Peabiru: Connecting Past and Present

The efforts to identify and recover the Peabiru are important for multiple reasons. By studying what remains, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of the social, economic, and cultural exchanges among the pre-Columbian indigenous communities for which it had a central role.

Recovering and preserving the Peabiru presents a way for the groups that still inhabit the regions to honor their ancestors, contributing to cultural continuity. It holds a significant cultural and spiritual value to them, and therefore, it is a crucial endeavor in the valorization of their history.

The Peabiru Pathway is more than just a series of trails; it is a bridge to the past. Its preservation contributes to revitalizing this precious, but often forgotten, part of South American history.