The Koreas of today are two nations technically still at war; relations between them run hot and cold. Despite this, Korean history runs deep, with some historians claiming a 5,000-year history. Divided between three kingdoms for centuries, only one prevailed-Goguryeo. Korea became a sort of historical crossroad.

An Unintended Sanctuary

The Korean War ended in 1953, dividing the country into political opposites. The “split” became the DMZ (Demilitarized Zone). This buffer, a nearly 250-kilometer-long, four-kilometer-wide strip, is fortified, mined, and under constant observation. Yet this strip remains relatively untouched, a surprisingly biodiverse hotspot. Biologists estimate that some 5,000 species reside here, including endangered species. This includes the Asiatic black bear, long-tailed goral, and red-crowned crane.

Even migratory birds rest here, in a spot covered with barbed wire and watched. It remains a pleasant contradiction in a hotspot.

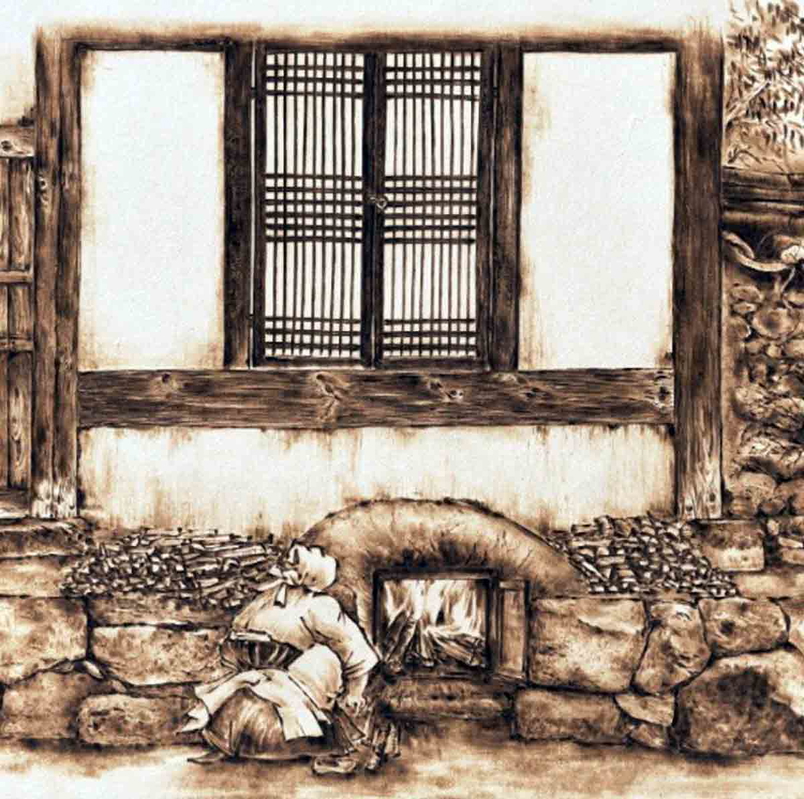

The “Warm Stone” Heating

The Koreans, like the Romans, used a heated underfloor system to keep their houses warm during the autumn and winter. Unlike the Romans’ vertical flues, however, this traditional Korean system used horizontal ones. Called “ondol” or warm stone, channeled heat from a wood-fired stove through the pipes beneath the floor. As the heat rose, this provided warmth for living spaces. Smoke from the stove vented out via a chimney. The house’s stone floors retained the heat for some time after the fire went out.

As a heating system, this was great, but ondol did more. This system played a significant role in Korean life. Unlike Western homes, people slept and ate on the floor, mingling in daily life. Ondol dates back over two millennia, with evidence found in archeological digs.

Ondol represents a clever way to heat a home using engineering available at the time. It’s said that ondol inspired other societies to copy it!

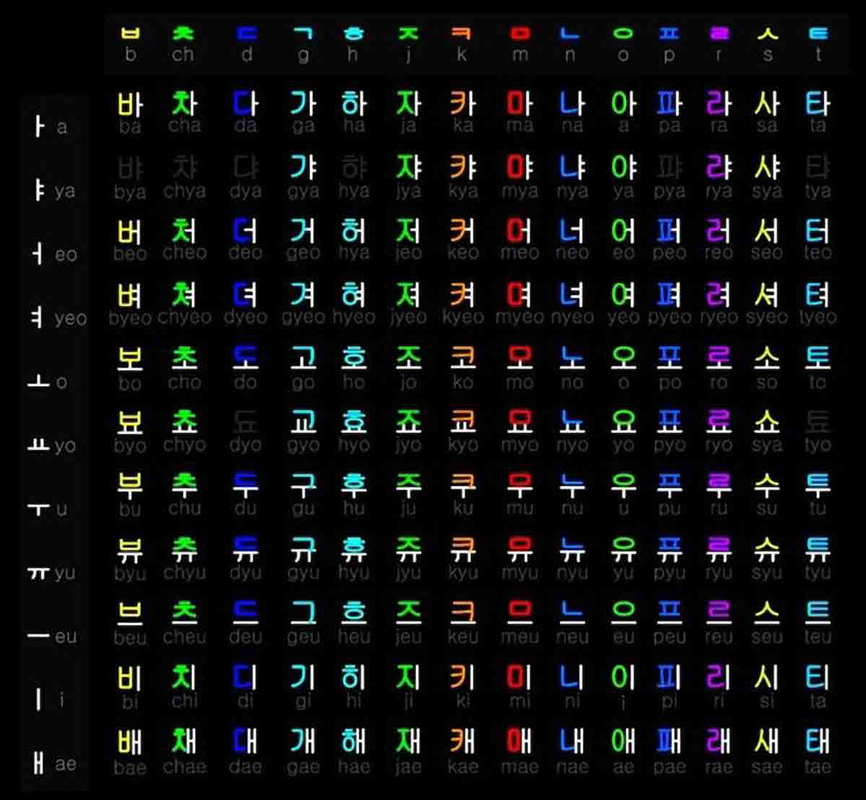

A Deliberate Writing System

Writing systems are a complex thing born from a need to communicate. Most are native grown or spread via cultural contact. Yet Hangeul, Korea’s writing system, resulted from a royal order. King Sejong (Joseon Dynasty) in 1443 mandated the creation of a new language. This language, called Hangeul, short for Hunminjeongeum, meaning “correct sounds for instructing the people,” was developed for one purpose. King Sejong sought to break the nobles’ exclusive monopoly on writing.

Korean nobles used Classical Chinese, a complex system requiring years of study. This eliminated commoners from writing or learning. Hangeul consisted of twenty-four letters, each with a separate sound. Written in compressed blocks, Hangeul’s arrangement and logic made for easy learning. Apart from breaking the elite’s learning monopoly, Hangeul’s unique Korean origins also helped reduce Imperial China’s influence.

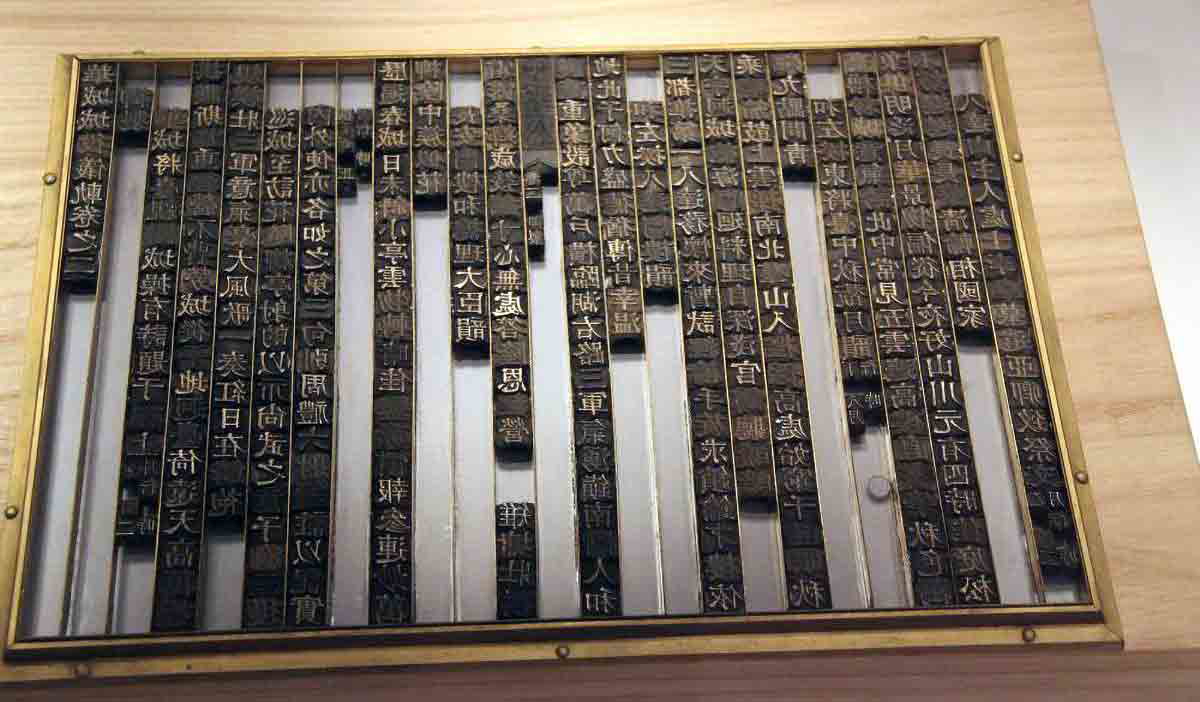

Meet the Pre-Gutenberg Press Book

The Gutenberg press, invented in 1455, revolutionized European printing. Printers could now cheaply produce copies of the Bible and other texts, resulting in durable documents. Yet unbeknownst to the West, Korean monks in 1377 created the oldest metal plate printed book. These Goryeo Dynasty monastics predated Europeans by 78 years!

This book, Jikji Simche Yojeol or “Anthology of Great Buddhist Priests’ Zen Teaching,” was printed at the Heungdeok Temple. The monks, especially the monk Baegun, created this book to educate and preserve Buddhist teachings. Plus, this knowledge could easily be made and disseminated. Their secret lay in the bronze movable metal type made possible by Korea’s metallurgical skills.

The movable type proved superior to traditional woodblock printing. Artisans would carve a complete page into the wooden blocks. Next, the artisans inked the blocks and pressed them onto paper. Unlike the changeable metal types, new pages or updates meant repeating the process.

Ironically, the only surviving copy of the Jikji resides in a French museum. The Jikji’s demonstrates that parallel solutions to similar problems can happen.

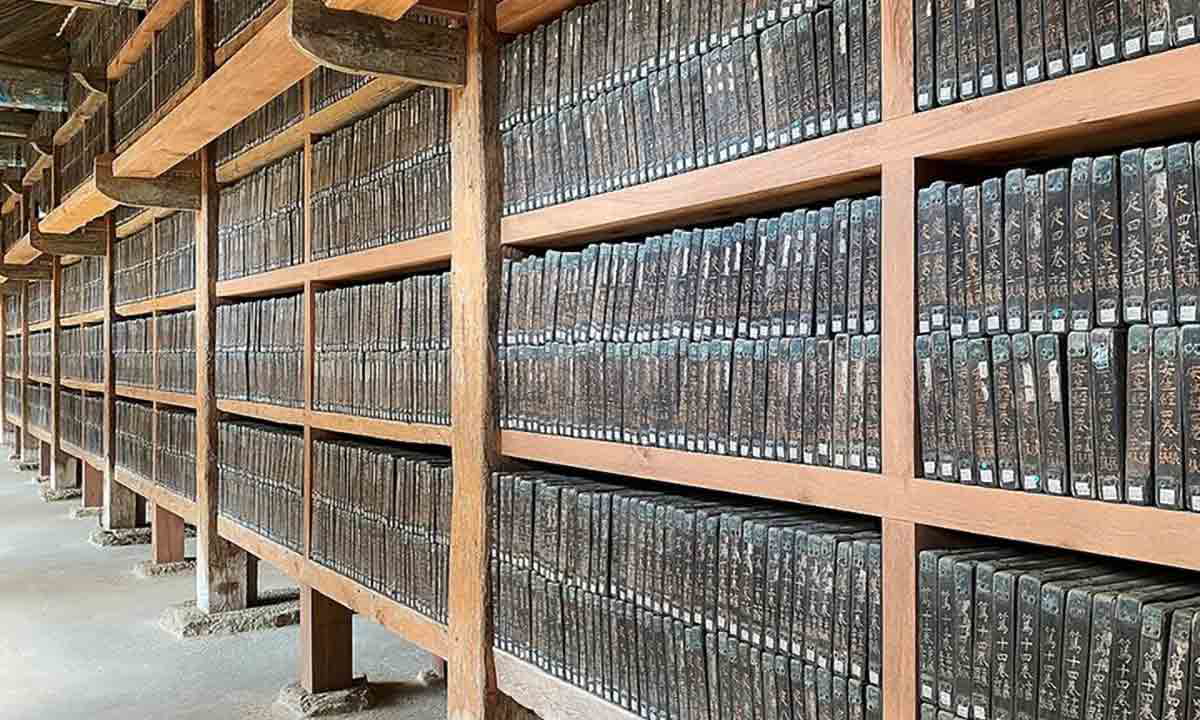

81,258 Blocks of Devotion

As the number displays, the Koreans produced the Tripitaka Koreana-a, a collection of over 80,000 Buddhist scriptures around 1251 CE. Like the later Jikji, monks produced these religious texts during the Goryeo Dynasty, a high point for Buddhism in Korea.

The Tripitaka Koreana is the most complete collection of Buddhist texts in the world. Work on the blocks commenced in 1237 CE and finished in 1248. Many Buddhist woodblocks were destroyed during the Mongol invasions. Each block is made from birch and treated with smoke, brine, and drying to prevent warping or insect damage. With no known mistakes, the blocks number over 6,568 volumes on 81,258 blocks. Now housed at the Haeinsa Temple, this national treasure of blocks is available for public viewing.