Pidgins and creoles are two distinct types of languages that have emerged and developed in contexts of intense linguistic (and cultural and economic) contact. A pidgin is a simplified language with a limited vocabulary that has originated to bridge the communication gap between two groups without a common language. In contrast, a creole is a pidgin that has been gradually refined and enriched by a new generation of speakers who now consider it their first language. Understanding the differences in pidgin and creole formation (and development), as well as the similarities and differences among pidgins worldwide—from the Chinook Jargon in Canada to Naijá in Nigeria—will help us shed light on the adaptability of languages and the resilience of their speakers.

What Is a Pidgin?

As Ronald Wardhaugh, author of An Introduction to Sociolinguistics, reminds us, most languages, including English, French, Italian, Latin, and Arabic, have developed in what he calls “contexts of language contact.” Pidgin and creole languages are no different. A pidgin is a grammatically simplified language that emerges to facilitate communication between two (or more) groups that do not share a common language—essentially when speakers of entirely different languages need to communicate.

Pidgins are essentially contact languages; to put it with Wardhaugh, they are “the product of a multilingual situation in which those who wish to communicate must find or improvise a simple language system that will enable them to do so.” Pidgin formation scenarios may be extremely varied, but the starting point is always the coming together (or clashing) of different linguistic groups that require a mutual means of communication.

This is what has consistently occurred in colonial countries around the world, from the United States and Canada to Africa, India, and the Pacific. Pidgins are colonial products par excellence. They are also “trade products,” closely tied to long-standing trade patterns between Europe and the rest of the world, including the slave trade. Pidgins have traditionally emerged in locations close to (or easily accessible from) the sea or the ocean, on islands across the Indian and Pacific Oceans, as well as along the coastlines of Africa and the Americas.

It should not come as a surprise, then, that linguistic studies have historically assigned a marginal position to pidgins (and their speakers). They have too often been considered, as Wardhaugh notes, as “an uninteresting linguistic phenomena, being notable mainly for linguistic features they have been said to lack (e.g., articles, the copula, and grammatical inflections) rather than those they possess.”

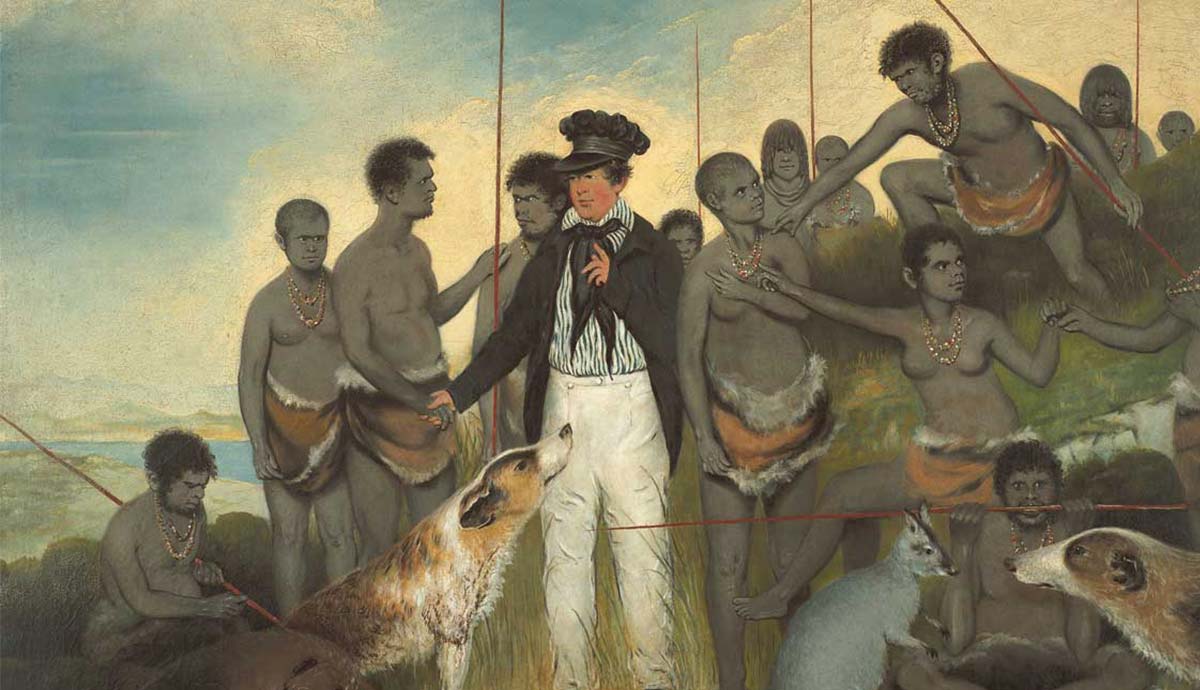

Similarly, non-European speakers of pidgin languages have frequently been treated with disdain. In colonial contexts, there was an expectation that Indigenous people would learn the languages of their colonizers, such as English, French, Portuguese, as well as Italian and German, rather than the other way around. In this context, European languages represented the so-called superstrate languages, that is, the (socially, politically, and economically) dominant languages.

Interestingly, Wardhaugh points out that “the European colonists who often provided the superstrate varieties for pidgins and creole languages were rarely speakers of prestige varieties of their language.” In other words, the English (or French) spoken by trappers, fur traders, settlers, or convicts in British colonies, like Canada or Australia, was not the same as that spoken by the wealthiest members of society. It is also noteworthy that not all pidgins have a European superstrate; for example, Russenorsk, now extinct, borrowed terms from Russian and Norwegian.

From Pidgin to Creole

Pidgins essentially originate and develop to fill communication gaps between groups. Some pidgins eventually die out, that is, they become obsolete, particularly when economically disadvantaged groups adopt the dominant language—such as English or French—as their first language, either voluntarily or under duress. This phenomenon happened consistently in residential schools and missions across North America and Australia, where Indigenous children were forced to speak English, the superstrate language.

In other contexts, however, a pidgin may stabilize and evolve. While a pidgin can never be a native language, it can become the mother tongue of a specific community, serving as the first language for future generations. When this occurs, that is, when a pidgin expands and develops becoming the first language spoken by a specific group, linguists tend to call it a “creole” language—although creoles and pidgins remain overlapping categories with overlapping characteristics. In some regions, a creole might still be informally called a “pidgin.”

In cases like that of the Tok Pisin (literally, “bird talk”), spoken in Papua New Guinea, the terms “pidgin,” “creole,” and “expanded pidgin” are often used interchangeably. Unlike pidgins, creole languages tend to be more elaborate, fully-fledged, and, most importantly, native to a specific group. While pidgin formation requires a (paradoxically complex) “simplification” and reduction of the language’s use, syntax, and morphology, the process that leads to the creation of a creole language is one of expansion. A creole originates when its speakers broaden the language’s vocabulary when particular words and phrases are used across various contexts. Typically, novels are written in creole languages, not pidgins.

In a way, creole languages arise from the contributions of both adults and children. While adults are responsible for expanding the language’s use, children who grow up in multilingual (and possibly multicultural) environments “regularize” the language, shaping it as they learn.

In Canada

As European traders and settlers flooded into North America, various English-based pidgins developed as contact languages across present-day Canada from as early as the 16th century. One notable example is the so-called Algonquian-Basque Pidgin, which originated in the late 16th century around the Gulf of St Lawrence and spread across the Atlantic Provinces, from present-day Newfoundland to Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Quebec.

As Basque whalers, cod fishermen, and merchants began to establish fishing settlements along the coast of Labrador and Newfoundland, they came into contact with the local Algonquian-speaking populations. The language these groups spoke to communicate up until at least 1710 was the Algonquian-Basque Pidgin, a simplified mixture of Basque, Gascon (the Romance Occitan dialect spoken in the French region of Gascony), Innu-aimun (the language of the Innu, or Montagnais-Naskapi), and Mi’kmawi’simk, the language of the Mi’kmaq.

In the regions now known as Nunavut, Nunavik (northern Quebec), and Nunatsiavut (northern Labrador), as well as in the neighboring areas of the eastern Arctic, an English-based Inuit pidgin emerged as the main communication tool between Inuktitut-speaking Inuit communities and English and Dutch-speaking traders, whalers, and settlers. This contact language, a simplified blend of English and Inuktitut terms, is known as Inuktitut-English Pidgin. Its use has gradually declined over time.

In the Western Arctic region, particularly along the Mackenzie River and the Mackenzie River Delta, another Inuit pidgin, the so-called Eskimo Trade Jargon, emerged in the 19th century. The Inuit population in this area, historically referred to as Eskimo, Western Canadian Inuit, or Mackenzie Inuit, now prefers the name Inuvialuit, which means “the real people.”

When European whalers and traders first encountered them in the 19th century, they represented the largest Inuit population in the Canadian Arctic. The Eskimo Trade Jargon likely emerged around this time. It was so widely used not only among Inuit and Europeans but also among Inuit and their Athabaskan-speaking neighbors to the south, particularly the Gwich’in (Dinjii Zhuu) Nation, that it quickly developed (at least) four different dialects.

Chinook Jargon

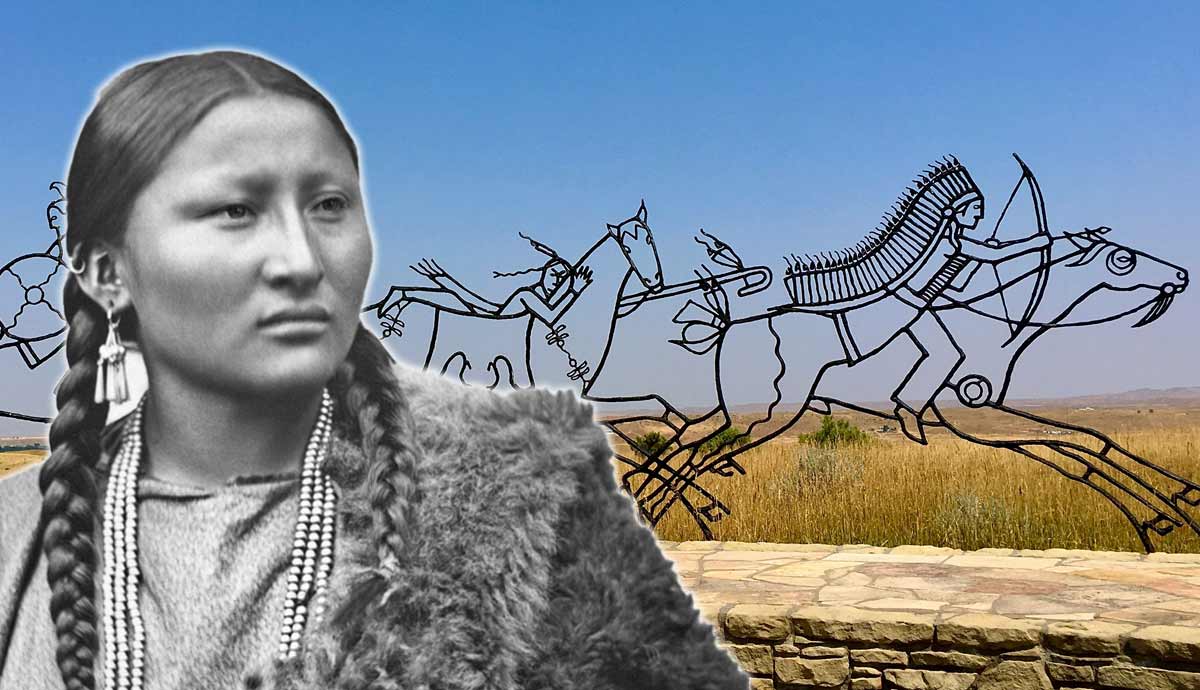

Similar to how English serves as a lingua franca in many countries and Kiswahili (Swahili) is East Africa’s lingua franca, Chinook Jargon was used as a lingua franca among First Nations in the Pacific Northwest. Although some linguists and historians suggest that it may have existed prior to European contact, it is generally recognized as a product of the interactions between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, and, by extension, as a product of British colonialism.

Chinook Jargon originated as a trade language in the early 19th century along the lower Columbia River, where European traders, trappers, and Catholic missionaries were in desperate need of a common means of communication with the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw (pronounced kwok-wok-ya-wokw), Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka), Coast Salish, Nuxalk (or Bella Coola), and Tsimshian tribes.

Over time, Chinook Jargon (also known as Chinuk Wawa) spread as far south as northern California, covering Oregon, Idaho, and Washington, and as far north as the southern regions of Alaska, reaching its peak usage in the 1870s. Essentially a trade language, it was extensively employed by Indigenous tribes, maritime traders, miners, trappers, pioneers, and employees of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), which earned it nicknames like “the Hudson Bay language,” or “the old trade language.” It borrows words and grammatical forms from both English and the Indigenous Wakashan languages spoken throughout the Pacific Northwest, particularly the Chinook language.

Over the years, Chinook Jargon has influenced the English language as well, with Chinook Jargon words now found in the speech of non-Indigenous English speakers and as placenames along the West Coast of North America.

Words from the Chinook Jargon also appear in historical texts, such as the History of the Expedition under the Command of Lewis and Clarke, which chronicles the expedition led by Lewis and Clarke between 1803 and 1806, as well as in Mark Twain’s Sketches New and Old (1875), and in the writings of the Mohawk Canadian writer Pauline Johnson (1861-1913), also known as Tekahionwake, notably in The Legends of Vancouver. Washington is even referred to as the Chinook State. Today, however, virtually no one in North America speaks Chinook Jargon, and it is considered nearly extinct.

Nigerian Pidgin

The various names by which Nigerian Pidgin is known reflect its origins, dating back to the Atlantic slave trade in the 17th century. Sometimes referred to as Naijá, or simply Pijin or Vernacular, for decades it has been known as Broken (or Broken English). Nigeria has a long-standing history of contact with Europeans, beginning with the Portuguese who arrived on the Nigerian coasts—particularly in the Niger Delta—as early as 1472.

Naijá was originally a Portuguese-based pidgin that originated when the Portuguese, after exploring and mapping the coastline, began to interact with the diverse local communities of the Niger Delta and trade palm oil, weapons, bronzes, and bronze manillas with the Kingdom of Benin, which governed the forested region now known as southern Nigeria since the 1200s CE.

The fact that coastal communities lacked a well-established lingua franca facilitated the establishment of Naijá in the region. However, it was not until the early 1900s that it began to spread across Nigeria, effectively breaking down communication barriers between ethnic and social groups.

After the Portuguese left the region, it was the turn of Dutch traders, followed by the French and the British. By this time, Naijá had already become a well-established (Portuguese-based) pidgin language in the area. From 1553 onward, British merchants regularly anchored their ships along what is now Nigeria’s West African coast, and by the 1800s, as the British began to promote English as the dominant language, Naijá evolved further.

The English language quickly superseded Portuguese as its principal lexifier, transforming Naijá into an English-based pidgin. Today, while English serves as the major lexifier, much of Naijá’s vocabulary comes from the various local African languages spoken by the communities first encountered by the Portuguese in the Niger Delta. These include several Edoid-based languages, as well as Hausa, Igbo, and Yoruba. Some words, like pikin and sabi, come from the Portuguese.

Despite being spoken by millions across Nigeria and West Africa, and being featured in popular music, television programs, and commercial advertising, Naijá has not yet been granted official status.

In Australia

As we have seen, over the years, as a variant of pidgin English often gains importance among its speakers, it tends to expand socially and linguistically, eventually becoming the primary language for Indigenous groups. In these cases, it may replace ancestral Indigenous languages among younger generations.

In Australia, the most widely spoken creole languages are Torres Strait Creole (also known as Yumplatok), used by Aboriginal communities in the Torres Strait Islands and parts of northern Queensland, and Roper River Kriol (or Fitzroy Valley Kriol), prevalent among Aboriginal groups in the far north of Western Australia and the Northern Territory. Both creoles not only incorporate grammatical and phonological rules from English and local Aboriginal languages but also some terminology derived from Bislama.

Bislama, also known as Beach-La-Mar or by its earlier French name, bichelamar, is a Melanesian English-based creole language spoken in the Pacific, particularly in Vanuatu, where it serves the national language. In its “pidgin phase,” it was used by Sea Islander sugar cane workers who had been “blackbirded,” that is, kidnapped and taken to Queensland to work on plantations.

The localized pidgin that originated on plantations became the base for not only Bislama but also a range of creole languages across the Pacific, including Pijin in the Solomon Islands and Tok Pisin in Papua New Guinea.

In their unique ways, Australian Creoles, Nigerian Pidgin, and the many English-based pidgins in what is now Canada, such as the Chinook Jargon and the Eskimo Trade Jargon, are more than mere communication tools. They provide a window into the colonial history of the countries they originated in, where they emerged as contact languages facilitating communication between Indigenous people and European newcomers. Their evolution from pidgins to creoles is a testimony to the power of languages and the resilience of the communities that speak them.