Ever since the European colonization of North America, there had been a desire to find the long-sought passage to the Orient. Columbus had set off in search of this shortcut to Asia in 1492 and, despite two hundred years of exploration by European cartographers, no easy access from Europe to East Asia had been found, leaving traders to circle the entirety of Africa and pass by India. Despite centuries of exploration and repeated failures to find a maritime route across the Americas, the belief persisted that the Arctic held the passage, known as the fabled Northwest Passage. With the alleged route’s location being narrowed down in 1845 two ships (the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror) were sent out in search of it, led by Captain John Franklin. Upon entering the Arctic, however, no one would hear from the Franklin Expedition ever again.

The Franklin Expedition: A Sea Route to the Orient

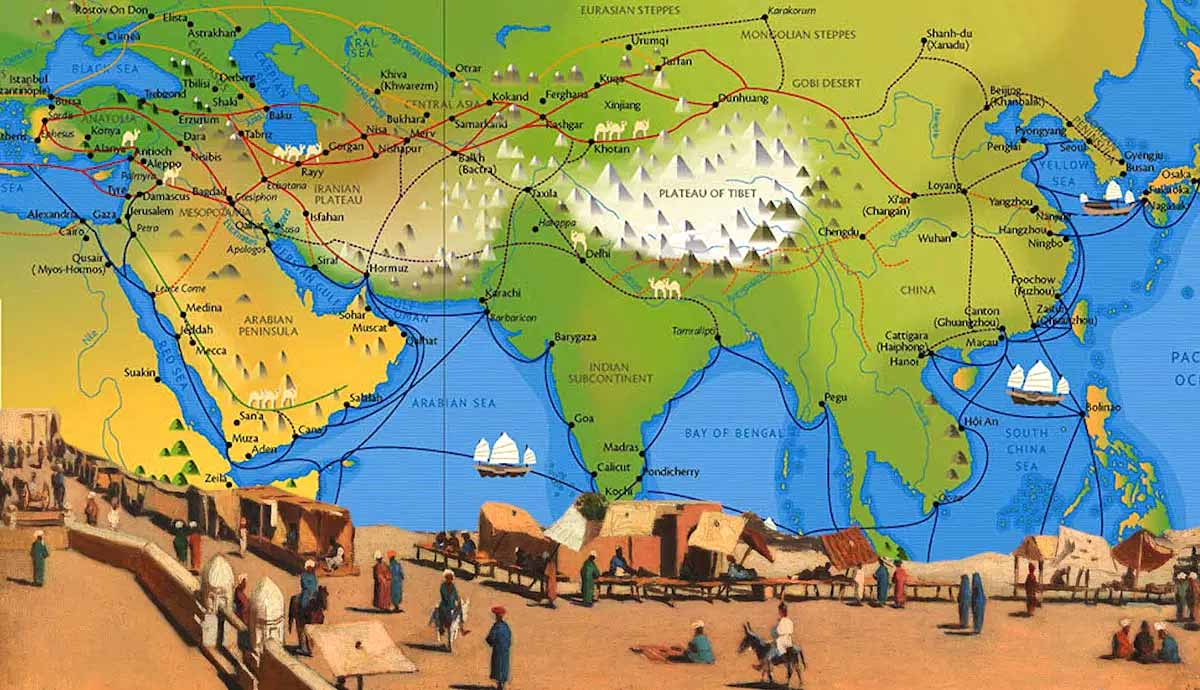

For nearly as long as people have lived in Europe, there has been an intense desire for far-flung and rare commodities originating from Asia. Entire empires were created, in fact, on the economic backs of this Eurasian trade even farther back than the Roman Empire. As technology improved, intrepid explorers started to look for new ways besides the existing and long over-land routes to reach Asian markets. By the 15th century, many explorers were going east, around the cape of Africa and through India, to reach the far east, but while this route allowed Europe to cut out the middle-men and deal directly with countries like China, it was still an immensely long, costly and difficult journey to take. Contrary to popular belief, no academics in Europe at the time believed the world was flat, but limited maps and navigation meant that going beyond the sight of the coast was seen as dangerous.

Eventually, it would be Columbus‘ famous journey in 1492 westwards that helped Europeans discover the Americas existed. This, however, was almost entirely by accident. It wasn’t the Americas that Columbus had been searching for, but rather a faster sea route to the Orient. The discovery would launch an explosion of European colonization and exploration of this new land. A driving constant over the next three and a half centuries was the belief that there was a large body of water passing through the Americas to Asia. Countless expeditions across both North and South America were launched in search of this mythical passage, with each one providing nothing but disappointment.

By the early 1800s, almost the entirety of the world map had been filled in, with the only oceanic region of the globe yet unexplored being the Canadian Arctic. With this in mind, England sent a number of explorers to the Canadian Arctic. By 1845, the eastern reaches had been thoroughly mapped out and the last unexplored corner of the map was believed to hold the mythical passage, where it only would require one final expedition to reveal its secrets. This would be the Franklin Expedition.

The Preparation

By 1845 much of the Arctic east had been mapped and explored, leaving less than 500 km of blank space left unfilled. It was there, in this last, tiny pocket of territory, that many firmly believed the mythical northwest passage lay. As such, the British admiralty began putting together an expedition, the final voyage to fill in the last piece of the map and finally find the elusive passage.

To meet these ends, a crew, hand-picked by the Admiralty, would be the ones who would serve aboard some of the most technologically advanced ships in the English fleet. The Franklin Expedition was also carefully provisioned with large amounts of food and supplies. Canned goods, a new advancement in food preservation, had been included in a quantity far exceeding the norm at 8000 tins. Other provisions went beyond usual considerations as a total of 1000 books were carried between the ships, intended to relieve boredom which often occurred on Arctic expeditions in the event of the vessels temporarily encasing themselves in ice.

Each member of the crew of the Franklin Expedition had been hand-picked and filled the ranks aboard the highly advanced HMS Erebus and HMS Terror. These ships possessed several highly modern innovations, in addition to being uniquely suited for Arctic exploration. The first aspect was the design of the ships themselves. Both had been built as bomb vessels, designed to hold massive mortars, and, because of this, had their hulls heavily reinforced to withstand the recoil, which made them excellent for the pressure of sea ice.

Both ships had been built in 1813 and the Terror had participated in the War of 1812. After their military service, both ships underwent a series of refits to convert them into Arctic vessels, including the reinforcement of the bows with iron plates and even thicker timbers behind the hulls. Most amazing was the use of cutting-edge steam-powered screw propellers on both of the ships. These inventions had first seen use six years prior. In addition to these new, retractable propellers and steam boilers was a highly advanced internal heating system that used the steam boilers to transfer heat throughout the ships for the comfort of the crew.

Of course, the admiralty required someone undeniably qualified for the expedition. While not their first choice, they did find such a man in Sir John Franklin. This would hardly be the first trip into the Arctic by Franklin, who had first made his way to the Canadian north in 1818, giving him nearly thirty years of experience in northern Canada by this point. A career navy man, Franklin had been at sea since the age of fourteen, in 1800, and had served at several famous battles, including the First Battle of Copenhagen and even the legendary Battle of Trafalgar. Arctic exploration was often considered unenviable and incredibly dangerous. A few of the initial selections for command of the expedition would turn down the offer before Franklin was selected, at the age of 59, to lead the voyage.

The Lost Expedition

Finally, on the morning of May 19th, 1845, the Franklin Expedition left Kent, bound for the Canadian Arctic. A mere two months later, the expedition had been encountered just off the coast of Greenland in the Baffin Bay by whalers as the Terror and Erebus awaited for favorable wind and weather to enter into the Arctic itself. This would be the very last time that any of the one hundred and thirty-four men would be seen alive. What exactly happened to the Franklin Expedition remains somewhat of a mystery. Even after over a century and a half, many of the exact details remain uncertain. Finally, in 2014, the wrecks would be discovered, a hundred and sixty-nine years after their departure.

It would take two years of silence from the expedition before any action was taken as Franklin’s wife and some members of parliament started to worry at the lack of communication from the vessels. The admiralty itself was slow to act, wishing to avoid panic and believing that long lengths of silence from the Arctic were not unheard of, given the chance that a ship might find itself frozen in ice for long periods of the year. In all, three search parties were dispatched in search of the vessels, to no avail. Only with the failure of the three attempts did national attention start to focus on the search. Soon enough, the Franklin expedition was a near-national phenomenon in the United Kingdom.

By 1852, many ships had ventured out into the Arctic in what then turned into a multi-national search, with even more ships becoming abandoned during the search. A grand reward of £20,000 (worth over £2 million in 2021) for anyone who could find Franklin and his crew fueling the effort. One of these ships was the HMS Resolute, which after becoming stuck and abandoned in the ice, was later recovered by American whalers and returned to England in good faith. From the timbers of this ship Queen Elizabeth gifted a desk to the US President, which still serves as the sitting president’s desk in the Oval Office, to this day. Beyond locating some early camp-sites used by the expedition, none of the search attempts discovered the fate of the crews.

The Fate of the North-West Passage

It wouldn’t be until 1859 that any conclusive evidence as to the fate of the Franklin Expedition was found, in the form of two notes. The first stated all was well. Later writings state that as of April of 1848 the ships had been trapped in ice for a full year and a half. The crew had abandoned the trapped vessels after the death of twenty-four of the crew, including Sir Franklin. Now on their own, the remaining hundred and five survivors were headed south, towards the mainland. This would hardly be the last piece of information found, as subsequent expeditions over the years found many more signs and remains of the crew and, after working with local Inuit peoples, they narrowed the remaining expedition members’ final resting place down.

The searches would continue long after the revelation of the crew’s fate as people continued to fill in the pieces little by little, including the ever-elusive shipwrecks. Somewhat ironically, it would be these searches that led to the large-scale and thorough mapping of the Canadian Arctic. Even with the Arctic almost entirely mapped out, it would not be until 1906 that the passage would be navigated, by boat, by one Roald Amundsen. At this time, it was clear that there was no reliable, year-round ice-free passage through the Canadian North, putting an end to the dream of Franklin’s expedition, as well as the pursuit so many others gave their lives for.

The Franklin Expedition: The Passage Lives On

While it might seem that the stories of these men had long since ended, recent developments have brought them to international attention. Increasing global temperatures have caused more and more regular melt in the Canadian north, which has renewed global interest in the possibilities of Arctic shipping lanes. In order to assert its sovereignty over the area, a number of Canadian expeditions were launched with the goal of finding the ships. Sure enough in 2014, the Erebus was found with the help of local Inuit. Two years later, the Terror was found, ironically, in the Terror Bay which had been named well before any knowledge of the wreck. While it has long since been established that disease and malnutrition were the main causes of death among the Franklin Expedition’s crew, the finding of the two shipwrecks would finally close a chapter on the long-sought expedition just as the Arctic that they sought to explore opens up to the world at large.