Since the formation of its empire, and particularly after the Partitions of Poland, Russia ruled over millions of Jewish people. From the late 18th century, they were restricted to an area of the western frontier known as the Pale of Settlement. The rise of nationalism in the 19th century inspired antisemitic sentiment among large parts of the Russian population, leading to violent attacks on Jews, their homes, and their businesses. These brutal attacks, often encouraged by government officials, were a constant cause of anxiety for the Jewish population and led to mass Jewish emigration from the Russian Empire.

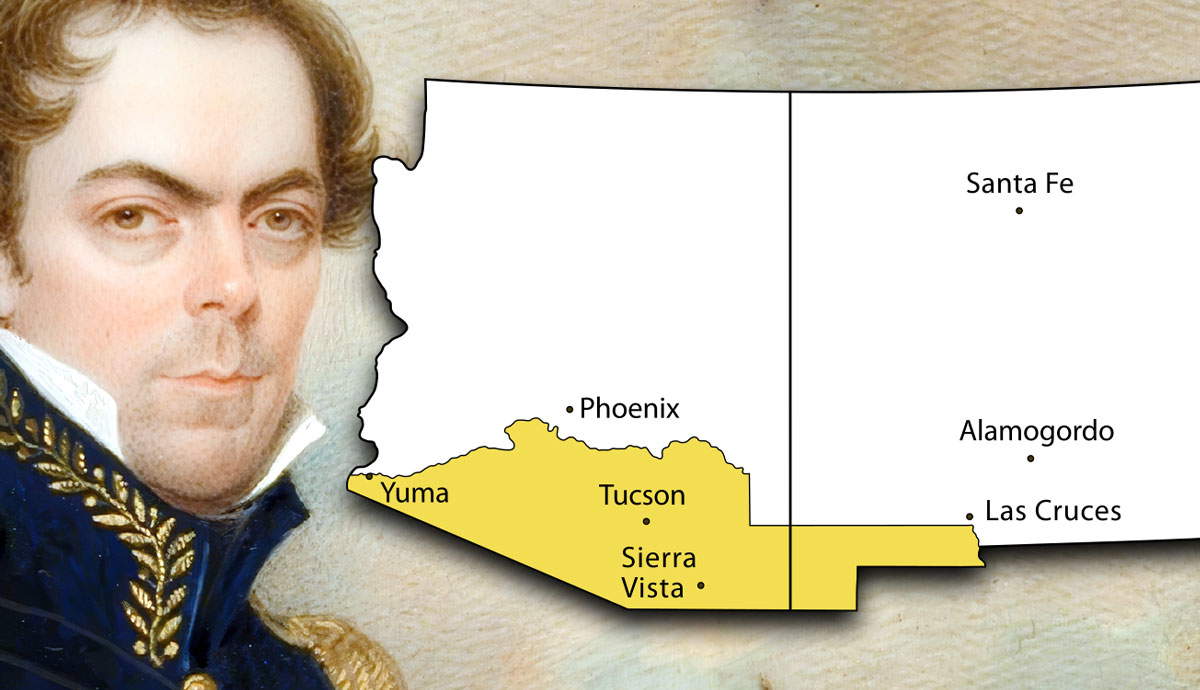

The Pale of Settlement

Ever since the expansion of the Tsardom of Muscovy across the Eurasian landmass, Russia’s leaders have struggled to rule over an imperial entity of millions of people from non-Russian backgrounds. Many of the empire’s subjects were not ethnic Russians nor Russian Orthodox Christians. The Romanov dynasty, who ruled Russia from 1613 to 1917, was troubled by the presence of a large number of Jews in the empire.

In 1762, Empress Catherine II came to power after overthrowing her husband in a coup. Her reign witnessed the further expansion of the Russian Empire into Poland and Ukraine. Following the Partitions of Poland, Catherine ruled over the largest Jewish community in the world. While Catherine favored some degree of religious tolerance for the Jewish people, under the influence of Russian advisors who espoused antisemitic tropes that the Jews had been responsible for Jesus’ death and that Jewish people were prone to stealing from ordinary Russians, she was persuaded to keep them away from the center of power and did not grant them the rights and protections that she had reserved for non-Jewish peoples.

In 1791, Catherine restricted the Jewish population to the Pale of Settlement, encompassing parts of modern-day Ukraine, Belarus, Poland, Latvia, and Estonia.

Jews living in other Russian cities were expelled, except for a small number of privileged families. Some Jewish communities in Central Asia and the Caucasus were exempt too because they were not considered a threat. Within the Pale, inhabitants were subject to restrictions of their movements or the jobs they could take. Catherine’s successors expanded or contracted the Pale as they saw fit. The region became the center of Jewish life in Europe.

Antisemitic Beliefs in the Russian Empire

Hatred of Jews had been deeply ingrained in European societies since the expulsion of Jews from the Levant. The Russian Empire was one of the most antisemitic states on earth. The levels of anti-Jewish bigotry varies under different Russian rulers; for instance, Tsar Alexander II was more benevolent than his father Tsar Nicholas I or his son Alexander III. However, the underlying fear and distrust of Jews among Russian elites remained constant throughout the period of Romanov rule.

The Orthodox Christian faith played a central role in Russian culture. The belief that Jews were responsible for the death of Jesus Christ was widespread in Christian teachings until the 1960s. Much of the peasantry throughout the empire was illiterate and the little education they gained was from Church services and schools. Theories about greedy Jewish landlords and merchants also abounded, enraging poorer people who thought they were being swindled.

Antisemitism in Russia evolved over time: the belief that Jews were an all-powerful force or that they wanted to create a communist state developed in the 19th and 20th centuries. The notorious Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a forgery by the tsarist secret police (Okhrana), claimed that there was a Jewish plot to control the world. These theories, combined with medieval tropes like the blood libel, inspired demonstrations of political violence against Jews.

The Pogroms of the 1880s

On March 13, 1881, Tsar Alexander II was travelling in St. Petersburg to the Winter Palace when he was attacked by members of the People’s Will, a revolutionary terrorist organization. Having dodged five prior attempts on his life, he survived an initial blast only to be blown up by a second bomb after stepping outside his carriage. Even though he was known as a reformer who had abolished serfdom, many revolutionaries did not believe the reforms had gone far enough and wanted to abolish the monarchy completely.

While some Jewish people certainly welcomed the tsar’s demise, local provocateurs claimed that the Jews had collectively been responsible for the tsar’s assassination and wanted to destroy Russia. This inspired a series of attacks on Jews throughout the Pale. This was not the first time Jews had been attacked en masse by crowds: prior disturbances had taken place in Odesa, Ukraine, in 1821 and 1871. These attacks were called besporiadki or ‘disorders’ but came to be called pogroms, or ‘devastation.’ They took place all over the Pale: Ekaterinoslav (Dnipro, Ukraine), Warsaw, Odesa, Balta, Kyiv, and other cities with big Jewish populations. Attacks were especially prominent on Christian holidays and Jewish communities struggled to respond.

Contrary to popular belief, these attacks were not directly ordered by the Russian government. While the new tsar, Alexander III, was a reactionary antisemite, he did not want to incite public disturbances which could lead to a revolt. The pogroms were locally incited by people angry at Jews for a litany of reasons, including the presence of Jewish businessmen in major cities.

Pogroms From 1903-1914

By 1883, the first round of pogroms had fizzled out following belated law enforcement action. However, there was new trouble for Jewish communities in the empire. The rise of ultranationalist groups such as the Black Hundreds and the polarization of society in the empire made the environment for Jews very dangerous. The Kishinev pogrom in 1903, which killed 49 people, signaled a deadly resurgence of violence against Jews. It also led to the rise of Jewish self-defense groups and increased support of Zionist movements across the Pale. Tsar Nicholas II and the Okhrana made little effort to stop the attacks, hoping that people’s anger towards the tsarist regime could be redirected towards Jews.

The 1905 Revolution and the defeat of Russian forces against Japan led to a new round of pogroms, this time backed by the state. Tsar Nicholas II was an avid reader of The Protocols and gave state backing to ultranationalist militias throughout the empire. In Odesa in 1905, 800 Jews were massacred by Black Hundreds militiamen and members of the local Greek mercantile community who resented competition from Jewish businessmen. This violence coincided with the rise of revolutionary ideologies in the empire, which attracted many Jewish followers.

By this point, antisemitic violence had become routine and Jewish communities struggled to find a consensus on how to respond. Notwithstanding political differences between Jews who supported communism, Zionism, territorialism or other ideologies, there was recognition for the need to defend themselves. Jewish militias began to appear, supported by other nationalist and revolutionary movements. These measures ensured that Jewish communities could establish a measure of safety.

WWI and the Russian Army’s Anti-Jewish Violence

Following the outbreak of the First World War, there was a brief period of unity within the empire and the Jewish community in the Russian Empire rallied to the tsar. Around 400,000-500,000 Jewish volunteers and conscripts served in Russia’s military in different capacities. Many hoped that large-scale military service would enable them to rise up in society; others believed that the war would be a catastrophe for Jews. There was little hope for them to rise up in the ranks above some junior officer roles and they were still not trusted by the Russian elite.

When Russian forces entered territory controlled by the Austrian Empire, they began deporting and attacking Jewish communities caught in the crossfire. Russia even deported Jews on their side of the border, accusing them of being spies for the Central Powers. Additionally, Russian troops routinely carried out pogroms and robberies of Jewish villages. Unlike prior pogroms, these atrocities were committed by army troops, not ordinary civilians. Russian troops were often drunk and abused by their commanders, leading to the breakdown of discipline. This was especially serious after defeats at Tannenberg and the Gorlice-Tarnow offensive which forced the Russian army to abandon much of Poland in 1915.

As the war continued, Russian army morale deteriorated, mutinies became increasingly frequent, and soldiers joined calls for revolution. Anti-Jewish violence continued to plague Jewish villages in the Pale. By the time of the February and October Revolutions in 1917, the military practically collapsed and Jewish soldiers faced difficult choices about what to do next.

The Russian Civil War’s Pogroms

The end of WWI and the Russian Empire did not lead to an end to antisemitic violence in the Pale of Settlement. On the contrary, violence towards Jews increased drastically in the chaos of the Russian Civil War. Many of the armies that fought in that war were poorly trained and led, meaning that they lacked the necessary discipline to curb excesses.

Among the anti-Bolsheviks, Jews were blamed for the October revolution, the collapse of Russia’s war effort, predatory business practices, and the general chaos throughout Eurasia. In this context, some 200,000 Jewish civilians in Ukraine, Belarus, and Poland were murdered. This total does not include Jewish combatants in the armies fighting the Russian Civil War.

The main perpetrators were the White Russian army, composed of conservatives formerly loyal to the tsar, the Ukrainian People’s Army, and other warlord bands. Notwithstanding the Ukrainian People’s Republic’s initial support for Jewish equality and rights, the Ukrainian army acted brutally towards Jewish populations. In towns like Zhytomyr, Kherson, and Proskuriv, Jews were hunted down and killed, reminiscent of their experiences during the 1905 Revolution. Similarly, when Polish forces entered the city of Lviv, they massacred Jews because they thought that they were loyal to Ukraine. The White Army believed that Jews caused the October Revolution and massacred Jews throughout the entire empire, not just within the Pale.

The violence of the Russian Civil War led to Jews making a variety of decisions based on their perspectives. Jewish combatants could be found in almost every military participating in the war and their community leadership became divided over who to trust. Because the Red Army managed to keep a lid on antisemitism in its ranks, many Jews joined that force even if they were not communist. Many other Jews just left the region entirely, either going to the Americas, Western Europe, or Palestine.

Jewish self-defense units reappeared in some major cities too. Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the famous Revisionist Zionist leader, cut a deal with President Symon Petliura of the Ukrainian People’s Republic to obtain weapons for Jewish militias in Odesa. Other Jewish militias were folded into state armies once it became clear that they weren’t needed anymore. The violence of the Civil War was thought to be the worst anti-Jewish violence in Europe to date. Few imagined the horrors to come.

The Pogroms in Jewish History

Anti-Jewish violence had plagued Jewish communities across Europe for centuries. The Inquisition, the First Crusade, the Khmelnitsky Uprising, and other historical events caused enormous suffering for Jews in Europe. However, the Russian Empire’s antisemitic violence proved to be a major turning point in the way Jews saw Europe. Jewish communities in the empire found solutions to remedy their people’s plight: flight, revolution, or assimilation. The term pogrom became a major part of the Jewish people’s lexicon.

Contrary to the theme of Jewish helplessness expressed by writers like Max Nordau or Haim Nachman Bialik, Jewish communities fought back against the pogroms. They organized militias of working class people or paid off local policemen to warn them about trouble. The large proportion of Jews with military experience helped communities prepare themselves for self-defense. They also had support from sympathetic minorities around the Russian Empire. As the violence increased, Jewish methods of self-defense evolved.

The abolition of the Pale of Settlement by the Bolsheviks gave Jews freedom in the Soviet Union they had not had during Romanov rule, and many Jewish revolutionaries assumed prominent leadership positions in the government. Jewish Bolshevik leaders during this period included Leon Trotsky, Lev Kamenev, and Grigory Zinoviev.

Many rose up the ranks of the Communist Party to express their devotion to the new state. At the same time, anti-religious and anti-business practices of the USSR forced many Jews to leave. Pogroms would resume with the rise of Nazism and, in the wake of Operation Barbarossa, many people fell upon their Jewish neighbors again. This made clear the direct line between tsarist-era pogroms and Germany’s plan for extermination.