In June 1215, a group of English Lords prevailed upon King John to accede to their demands surrounding several basic rights they felt were owed to free men, producing a work that would go on to be a heavy influence on English (and western) law – the Magna Carta.

The Signing of the Magna Carta

In the 1200s, King John of England had engaged in several unsuccessful wars on the mainland of France where he had held lands as a member of the Angevin part of the Plantagenet dynasty. The wars were expensive, draining much of England’s resources and angering much of the British nobility. By 1210, the “rebel barons” had been disillusioned by John’s perceived overreach, and, lacking a legitimate figure to place on the throne, concentrated on the rights they felt they were owed as free man. By 1215, they had come to open rebellion, capturing London, and forcing John into negotiations.

Contents of the Magna Carta

Magna Carta is Latin for “Great Charter.” The document only applied to the “free men” in England, primarily the nobility, excluding serfs and others of similar status. It generally seeks to enforce the rule of law, rather than a more arbitrary rule by kings. It protects a right to trial by jury, certain property rights, and opposed unlawful imprisonment.

Did the Magna Carta Result in Actual Changes?

Sort of. The Magna Carta had much more influence in later centuries than in its own time, and that influence was due to a sort of mythologized reputation of the document rather than the reality behind it. Several kings, including John and his immediate predecessors, did not always honor the Magna Carta. Pope Innocent III even opposed it, as the Roman Catholic church held to the divine right of kings.

As time passed, the Magna Carta’s terms evolved and became more and more a part of English laws. By the later medieval period, English kings were confirming all or parts of it when they took the throne. A myth even arose that the Magna Carta represented the rights of Anglo-Saxon England before William the Conqueror invaded in 1066, and that myth persisted even into the 1600s where some of the supporters of the English civil war used it for support (though Oliver Cromwell opposed it under his rule, referring to it as “Magna Farta.”

Does Any Part of the Magna Carta Still Apply?

While a vast majority of the Magna Carta is no longer relevant, as it was written for a more feudalistic society, four specific clauses remain as part of British law.

1. “The English church shall be free, and shall have its rights undiminished and its liberties unimpaired…”

13. “And the city of London [and other towns] shall have all its ancient liberties and free customs both by land and water….”

39. “No free man shall be taken or imprisoned or disseized (dispossessed of land or property) or outlawed or exiled or in any way ruined, nor will we go or send against him, except by the lawful judgement of his peers or by the law of the land.”

40. “To no one will we sell, to no one will we deny or delay right or justice.”

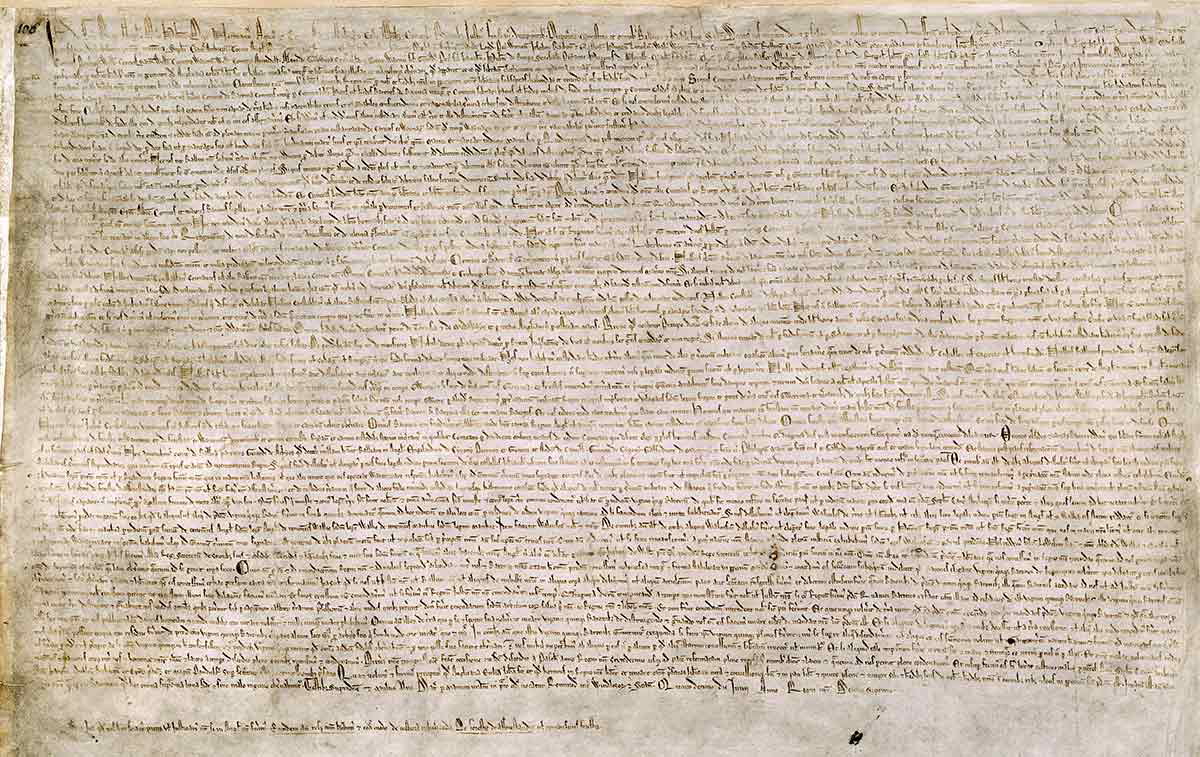

Existing Copies of the Magna Carta Today

Four of the twelve original copies of the 1215 Magna Carta are still in known existence. One at Salisbury Cathedral (which may have received its copy immediately after the signing), one at Lincoln Cathedral, and two at the British Library. Various official copies made over the next hundred years exist as well, including one from 1300 which was found at Harvard University in 2025.