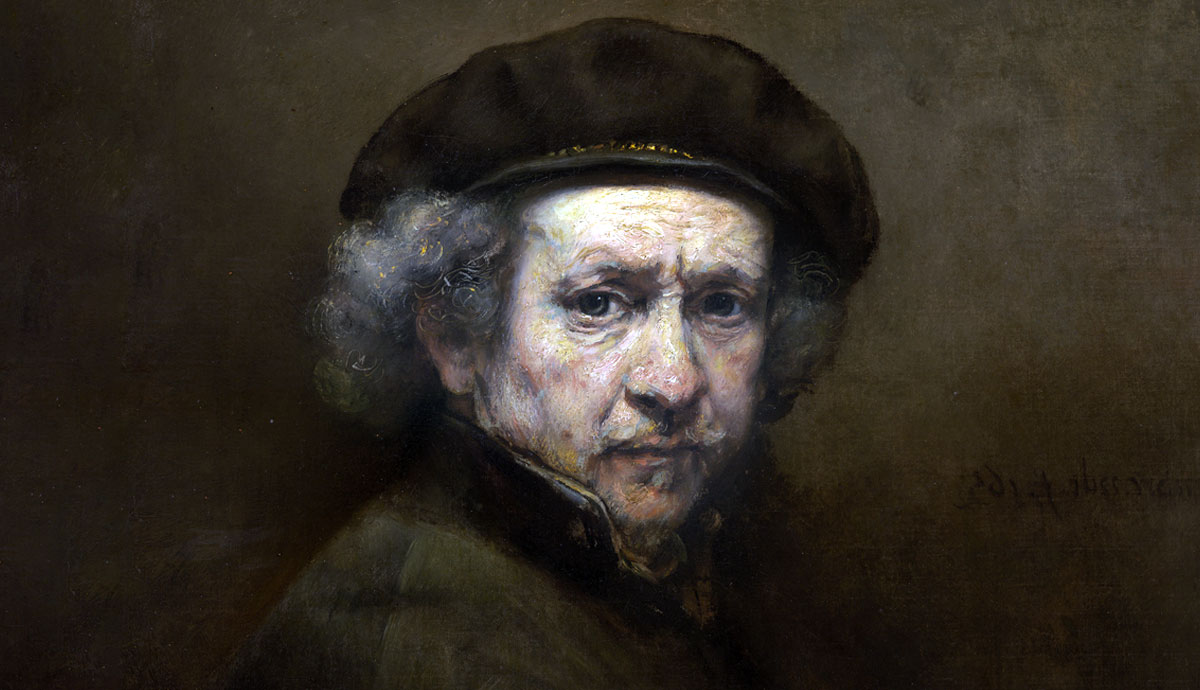

Rembrandt van Rijn was one of the world’s greatest masters and a painter specifically known for his treatment of light and shadow. Rembrandt usually used strong color contrasts and textured brush strokes to manipulate the perception of painted space. He used strong sources of light and contrasting shadows, constructing a sense of drama and mystery in his works. Read on to learn more about Rembrandt lighting, and the effect it caused on generations of artists, photographers, and filmmakers.

Rembrandt Lighting and the Famous Artist’s Technique

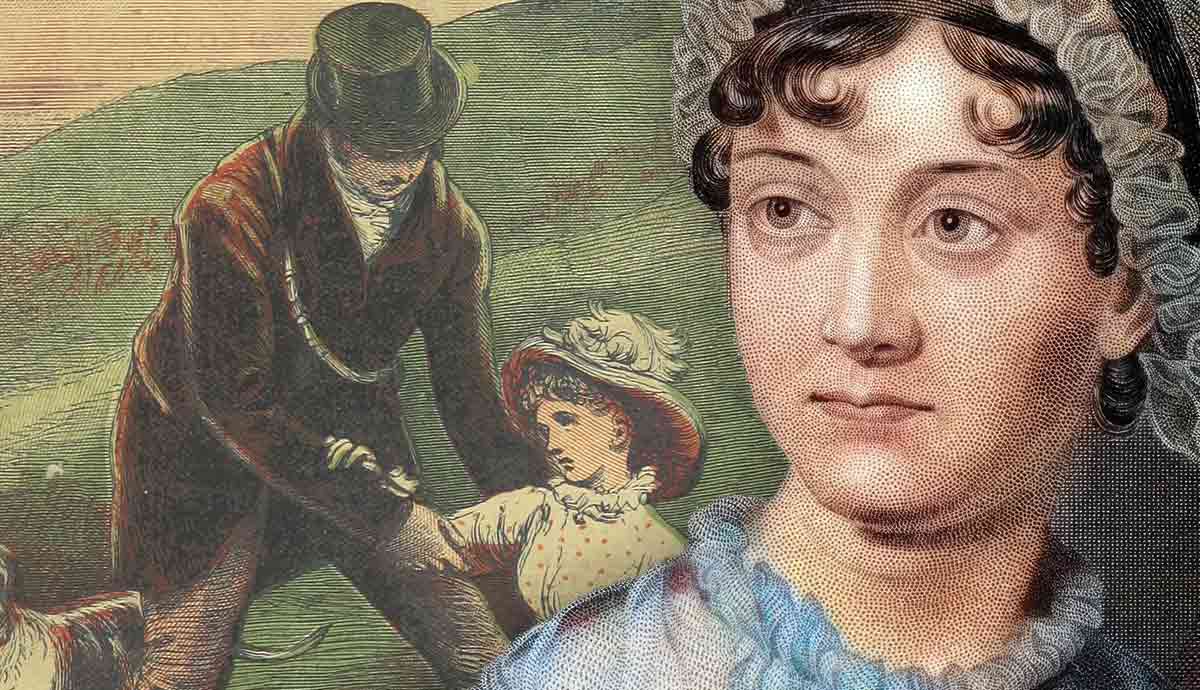

The famous Dutch painter Rembrandt van Rijn was a known master of manipulating light and shadow in his works. He used deep shades of brown, gold, and ochre to imitate intense light that gave extra dramatism to his compositions. Some art historians believe that Rembrandt specifically set up lighting in his Amsterdam studio to ensure dramatic and realistic contrast. He painted with broad brushstrokes, often laying paint with a palette knife. Instead of painstakingly painting every minuscule detail of jewelry and costume on his figures, he marked them with confident highlights and shadows, somehow making them more realistic.

Rembrandt was a miller’s son who managed to become the brightest and the most successful artist of his generation. Unlike many artists of his generation, he expressed no desire to study art in Italy, believing that Dutch painters already had enough inspiration at their hands. He was an avid collector of art and curiosities, with his studio filled with countless strange and lavish objects he admired.

Rembrandt was the known master of chiaroscuro, the expressive use of strong contrast between light and shadow typical for Baroque art. Usually, Rembrandt chose a single light source for his scenes and placed shadows according to their location and direction. The further effect of contrast was emphasized by plastic means: Rembrandt’s textured brushstrokes and built-up layers of paint created a natural play of light and shadow on uneven surfaces.

Present-day art historians often compare Rembrandt’s way of working with light with contemporary cinematography. For instance, the 2019 exhibition in the Dulwich Picture Gallery presented Rembrandt’s works as if they were stills from an unshot film, complete with captions imitating screenplay snippets.

Indeed, Rembrandt’s manipulation of stark contrasts and subtle tones creates an effect that feels fleeting and impermanent, as though capturing a single, perfectly suspended moment from a longer scene. However, Rembrandt’s true mastery lay in his ability to pinpoint and recreate a magical moment, crafting the emotional atmosphere of the scene through his careful interplay of light and shadow. His works invite contemplation and slow observation, encouraging viewers to pause and reflect, rather than rushing to move forward in the narrative.

The transformation of light and shadow, as well as the signature gold ochre tones used by Rembrandt, created confusion around one of his most famous paintings, The Night Watch. The work originally had no title and was known as Militia Company of District II under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq, according to the identities of the group depicted. For the first time, the name Night Watch was used in 1797, when another artist presented an etching based on the famous painting.

Over the decades, the thick varnish darkened and accumulated dust, making the entire scene appear much darker than it actually was. The dark tone suggested that the depicted scene took place during the night. However, during the 1947 restoration, the Rijksmuseum conservators removed the varnish layer and made a striking discovery. The entire scene was much brighter than expected and certainly looked like it was unfolding during the day. Moreover, the position of shadows suggested the time to be around 2 PM. Still, the title became so closely associated with the work that the Rijksmuseum team decided to leave it.

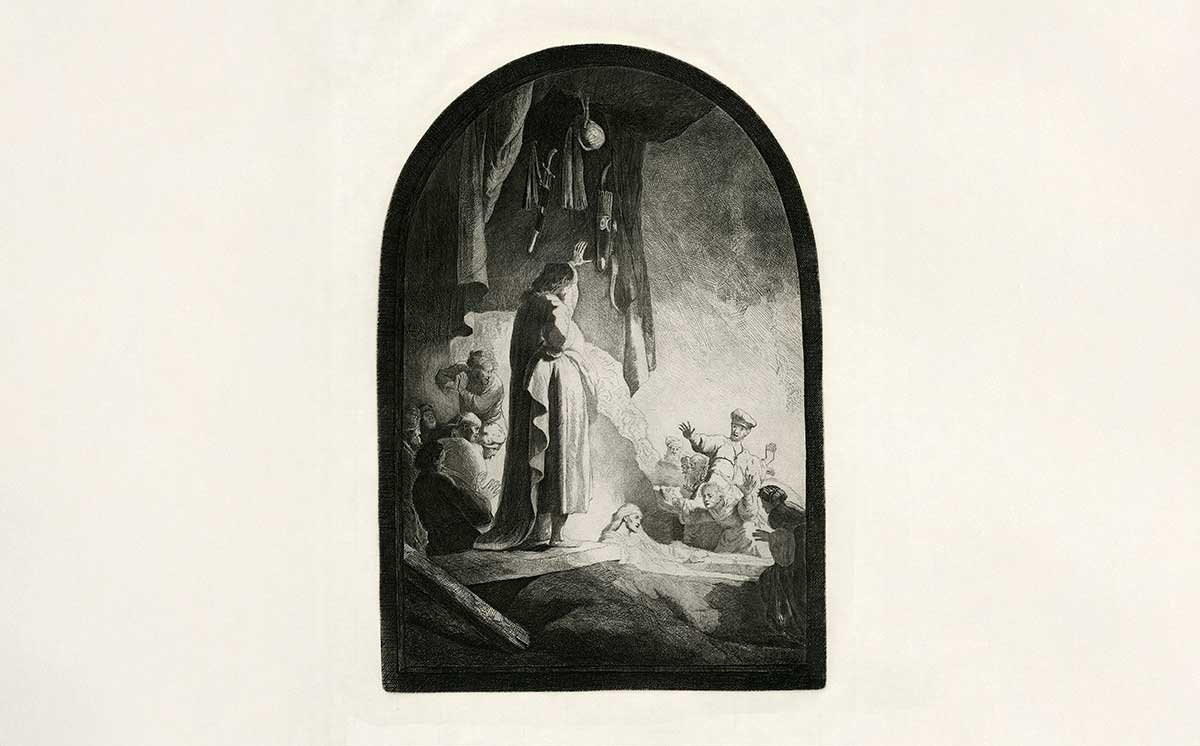

Rembrandt’s Etchings

Rembrandt skillfully manipulated light and shadow even in works that normally would not require such an approach. Etchings, for instance, normally were not regarded as artworks in need of extra visual depth. The technical process of creating it did not allow for creating optical illusions, or at least, this is what most artists believed. One of the brightest examples of his artistic inventiveness was the portrait of the preacher Jan Cornelius Sylvius. Breaking the canon of traditional, etched portraits, Rembrandt created an optical illusion of depth, adding shadows cast by Sylvius’ profile and hand that he was extending towards the reader.

Even in his etchings, Rembrandt actively used his method of placing deeper shadows on his figures’ faces. He also manipulated light and shadow to solve the problem of etched copper plates getting worn down. After several editions of printing, the lines on the etching plates lost their sharpness, and the images became lighter. While most artists accepted it as a fact, Rembrandt often added new lines and elements to change the directions of line and shadow and thus re-adapt the plate for further use.

Rembrandt’s Method: Artists Inspired

For centuries, many artists explored Rembrandt’s methods of working with light and adopted them into their own works. The most obvious and pronounced influence, obviously, was found in the works of Rembrandt’s students. Samuel van Hoogstraten adopted his master’s way of creating the illusion of space by manipulating light and shadows, and went even further with it, experimenting with perspective and architectural elements.

Govert Flinck, the artist whose works are sometimes confused with those of Rembrandt, perfected his use of light in portraits. Apart from Rembrandt, Flinck admired Peter Paul Rubens and managed to combine the influence of both in his art. Despite the age gap with his main teacher, Flinck died almost a decade earlier than Rembrandt and did not manage to fully realize his artistic potential.

Another famous admirer of Rembrandt was his compatriot Vincent van Gogh. Although seemingly radically different, their artistic styles had a lot in common. Both used highly textured brush strokes (Rembrandt even scratched fragments of paint with the back of his brush to give texture to elements like hair and eyes) and treatment of light. One of Van Gogh’s most famous early works, The Potato Eaters, with its single light source, dark shadows, and earthy tones clearly referenced Rembrandt’s way of work. Van Gogh famously said he would be happy to spend 10 years of his life sitting next to Rembrandt’s Jewish Bride with only stale bread to eat.

Rembrandt Lighting in Photography

In portrait photography, the term Rembrandt Lighting refers to a specific technique based on the use of a single light source and contracting shadows. To create dramatic and expressive portraits, photographers light one half of their model’s face and leave a shadow on the other. One of the typical features of the Rembrandt Lighting is the inverted triangle of light on the brow and cheekbone of the side of the model’s face.

According to some film historians, the term originated in the 1910s in the cinema industry, when studio owners expressed concerns about the supposedly poorly lit faces of actors. The mention of the famous artist’s name dismissed all concerns and established this type of lighting as an acceptable method.

The skilled use of Rembrandt lighting enables photographers to create expressive portraits that highlight the character and facial features of their models. Typically shot against a dark background, this technique draws attention to the model’s personality, adding dramatic depth to their emotions. The stark contrast of light and shadow is relatively easy to reproduce with the right equipment, making it a go-to method for many portrait photographers. It is also a favored technique among film noir directors, used to evoke a sense of dramatic mystery and a nostalgic retro effect.