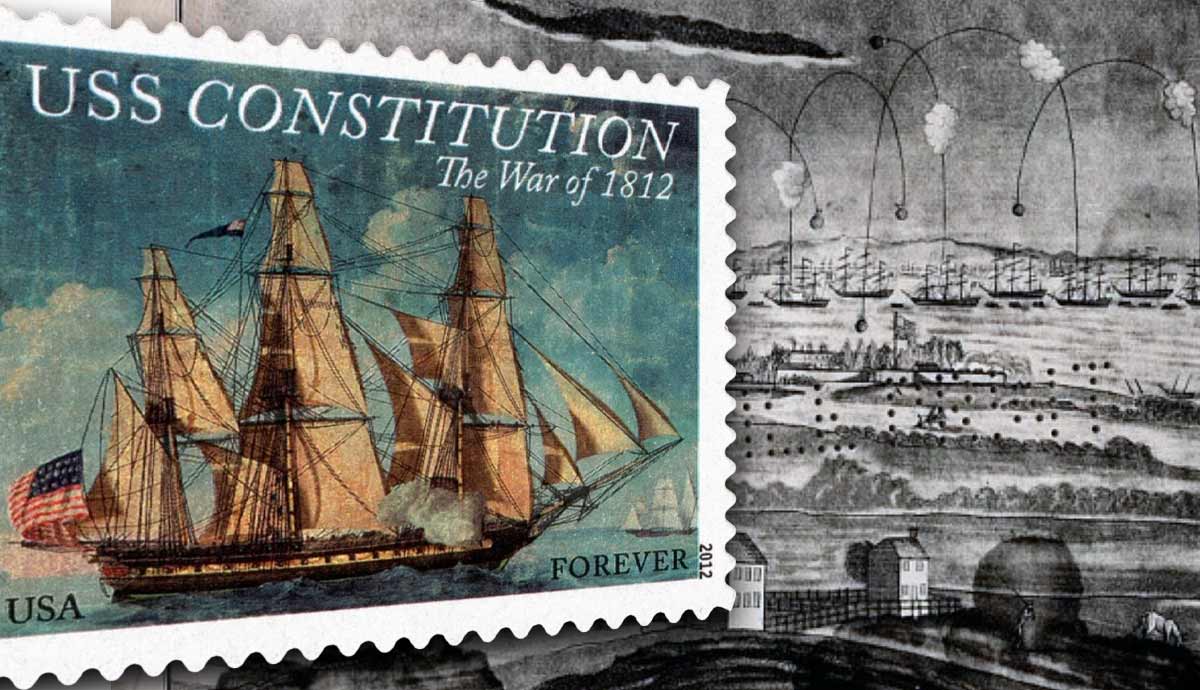

Despite being overshadowed by the American Revolution, the War of 1812 was paramount in preserving the newly won independence of the young republic. Caused by years of tensions over territorial disputes, the impressment of American sailors into the Royal Navy, and the British blockade of American trade with France during the Napoleonic Wars, the War of 1812 served as the first fully-fledged conflict for the United States’ newly created military. Without the help of field, naval, and coastal artillery, the war could have been America’s last.

After the Revolutionary War

During the War of 1812, artillerymen employed cannon in a similar fashion to their predecessors in the American Revolutionary War. Unlike the fight for independence, however, the United States was better prepared to counter the British second time round. With a regular army, established training procedures, and living artillery veterans with wartime experience, America was in a better position compared to their struggle for independence, but traditional roadblocks remained.

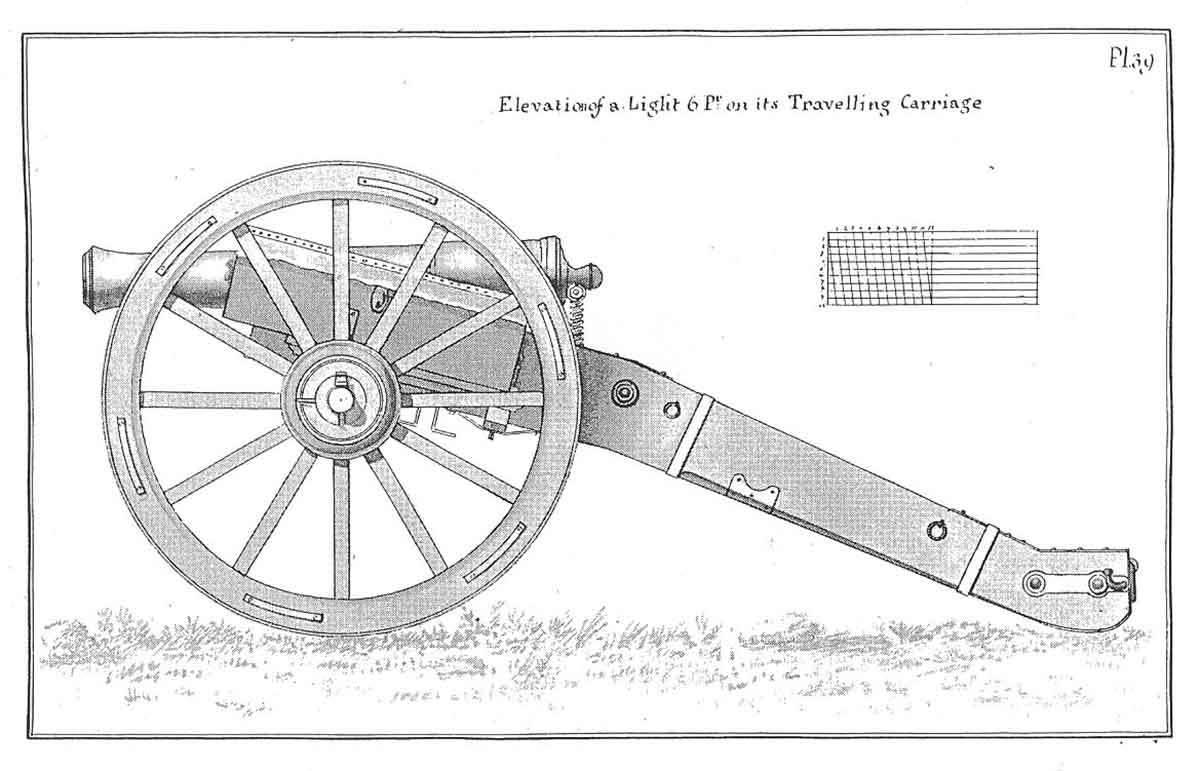

Although modern red-legs deploy artillery as an indirect weapon system, gun crews in the nineteenth century did not have the luxury of firing at what they could not directly see. As such, artillery during the War of 1812 was exclusively a direct fire asset despite lingering smoke that limited spotters’ fields of observation. Heavier artillery pieces could deliver projectiles over a distance of 1,000 yards towards adversary formations, but their effective range was significantly lower. Rifled gun barrels were not introduced in American conflicts until the Civil War, meaning that artillerymen facing the British fired smoothbore cannons which were notoriously inaccurate due to unpredictable trajectories of cannonballs as they were released from their barrels.

Due to these limitations, American field artillery commanders had to choose their emplacement positions carefully. Ideally, gun crews led their horse-drawn cannons to high terrain where enemy infantry lines could be observed for the duration of the battle, or where overlapping fields of fire from multiple batteries could prevent the enemy’s advance.

Technological Innovations

While artillery tactics in the War of 1812 resembled those of the American Revolutionary War, artillery technology had evolved during the intervening period, during which the entire European continent was engulfed in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

In a key innovation, British surgeon Henry Shrapnel introduced metal debris as an additional blast effect that increased the radius of projectile reach compared to traditional black powder explosives. These new capabilities paired well with the wide array of artillery pieces available to American gunners including the common 6-pounder gun, heavier iron cannons, and Canadian 24-pounders originally designed as an experimental weapon for the British Army. Over time, further technological innovations would bring different types of projectiles, fuses, and propellants to achieve different tactical outcomes on the battlefield.

The second major innovation during the period was the increasing use of rockets on the battlefield, pioneered by the British officer William Congreve. Fired via tripod-supported metal tubes, rockets offered artillerymen a lighter, more flexible, and quicker option compared to burdensome cannon weaponry. Despite these benefits, early rockets were notoriously inaccurate and were just as capable of hitting friendly targets as well as enemy ones. However, the psychological impact of rockets was undeniable, and over time they would be a key component in the toolkit of the US artillery in addition to guns and howitzers.

Impact in Battle

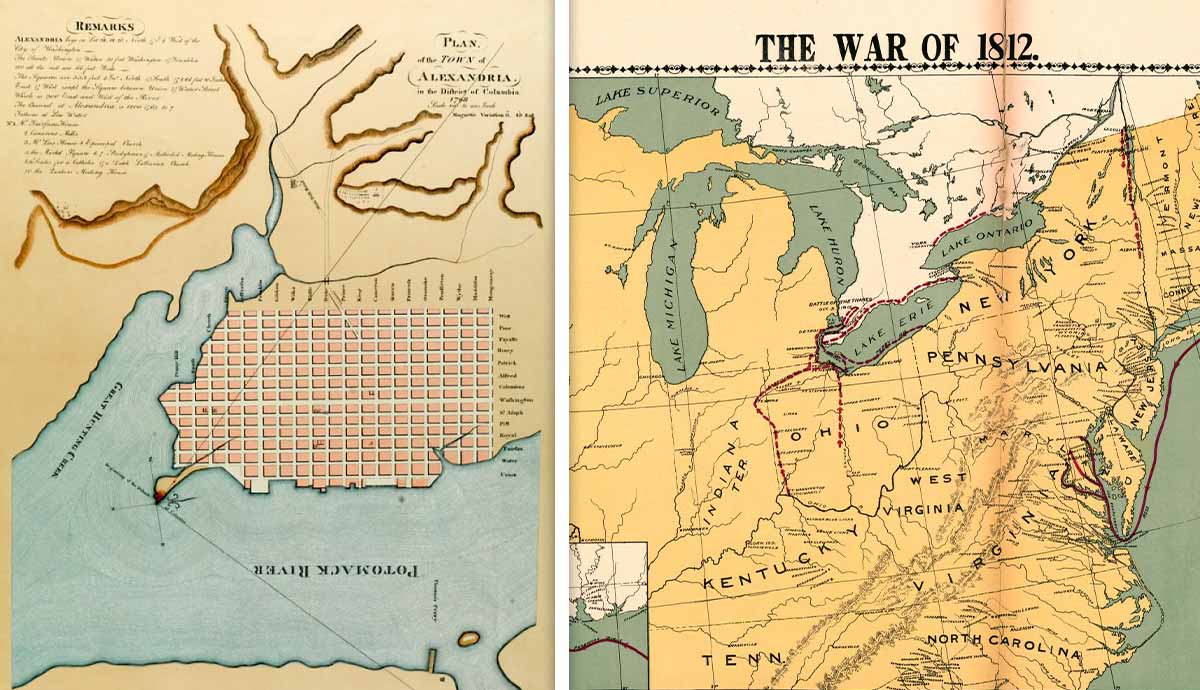

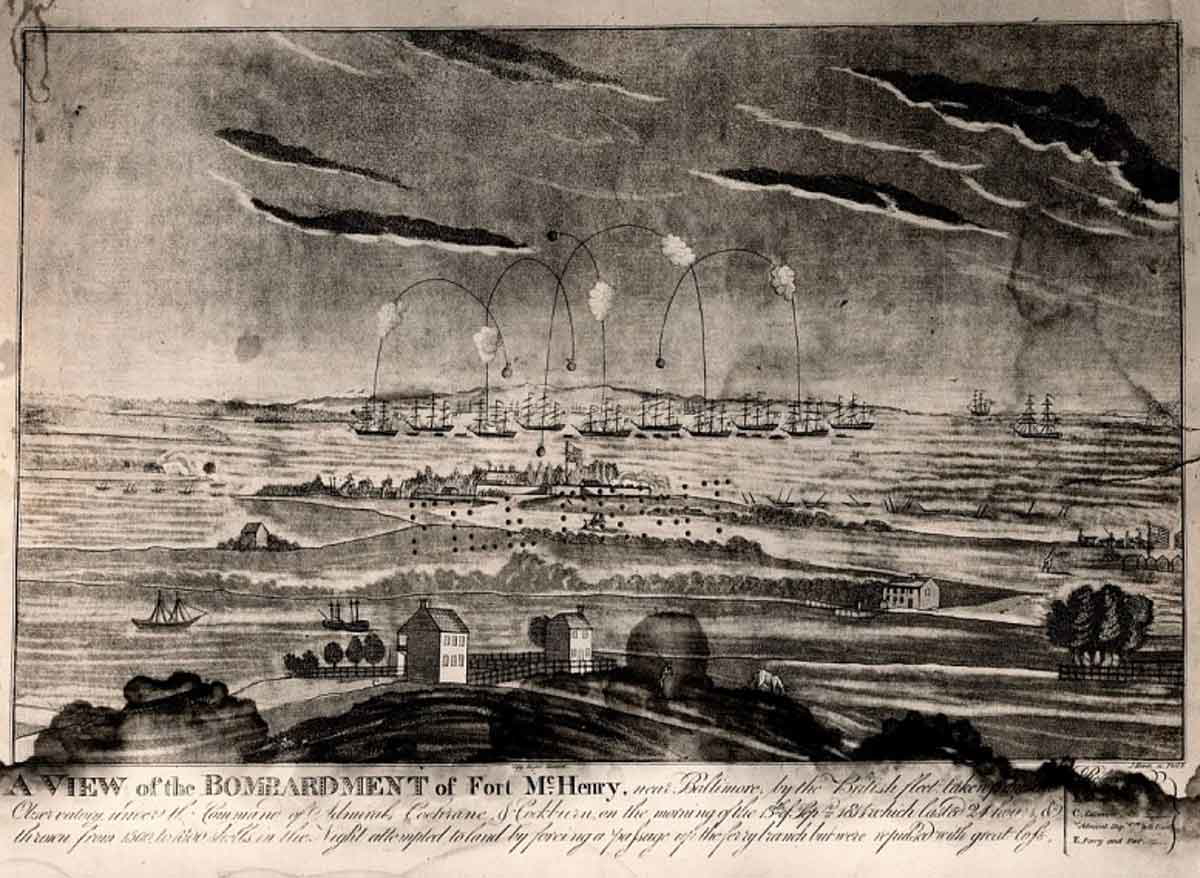

The War of 1812 witnessed battles on land and sea spanning from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. During nearly all the actions in the war, artillery performed supporting roles to infantry assaults rather than carrying out standalone engagements. During the Battle of Baltimore, for example, the British relentlessly pounded Fort McHenry’s defenses with naval bombardment. Captain Frederick Evans of the United States Corps of Artillery led American counterfire against the British ships with over 100 cannons, including heavy 24-pound pieces, and 10,000 soldiers. On the northwestern front, General William Henry Harrison was supported by artillery as he led American troops to victory in battles across Indiana and Ohio, including the war-altering death of Tecumseh at the Battle of the Thames in October 1813.

Artillery was also used to great effect as a defensive weapon during the 1814 Battle of Plattsburgh to repel the British from invading New York and force the enemy’s retreat into Canada. Gun crews proved invaluable in keeping nearby lakes under American control, restricting British supply lines. While a significant strategic victory, the clash highlighted the value of artillery even in small sections. At Plattsburgh, General Alexander Macomb’s gun crews were armed with only six artillery pieces of various sizes. Just as a seemingly inconsequential number of cannons established dominance on land, admirals had similar experiences at sea.

Naval Artillery

Not all American artillery utilized during the conflict was fired from land or at targets on firm ground. In fact, the War of 1812 saw major artillery duels at sea. Both coastal artillery and ship-based cannons enhanced the United States’ capabilities compared to the American Revolution. Over the course of the war, ironclad naval vessels became more popular due to the protection they enjoyed from enemy artillery. With an effective coastal artillery organization, as exemplified by the Battle of Baltimore, cannon fire protected American fortifications and naval assets at sea.

Offensively, Commodore Oliver Perry’s famous 1813 struggle against the British at Lake Erie enabled the United States to recapture Detroit. Armed with cast-iron carronades, Perry unleashed broadside volleys to destroy enemy ships at short-range. Despite immense damage to his flagship, Perry rowed a small rescue craft towards the USS Niagara where he assumed command and aggressively charged towards the British. Through surprise and disciplined gun crews, the United States was winning the war at sea. Over a year later, artillery bombardments dominating battlefields on land and water definitively secured the war’s end for the United States.

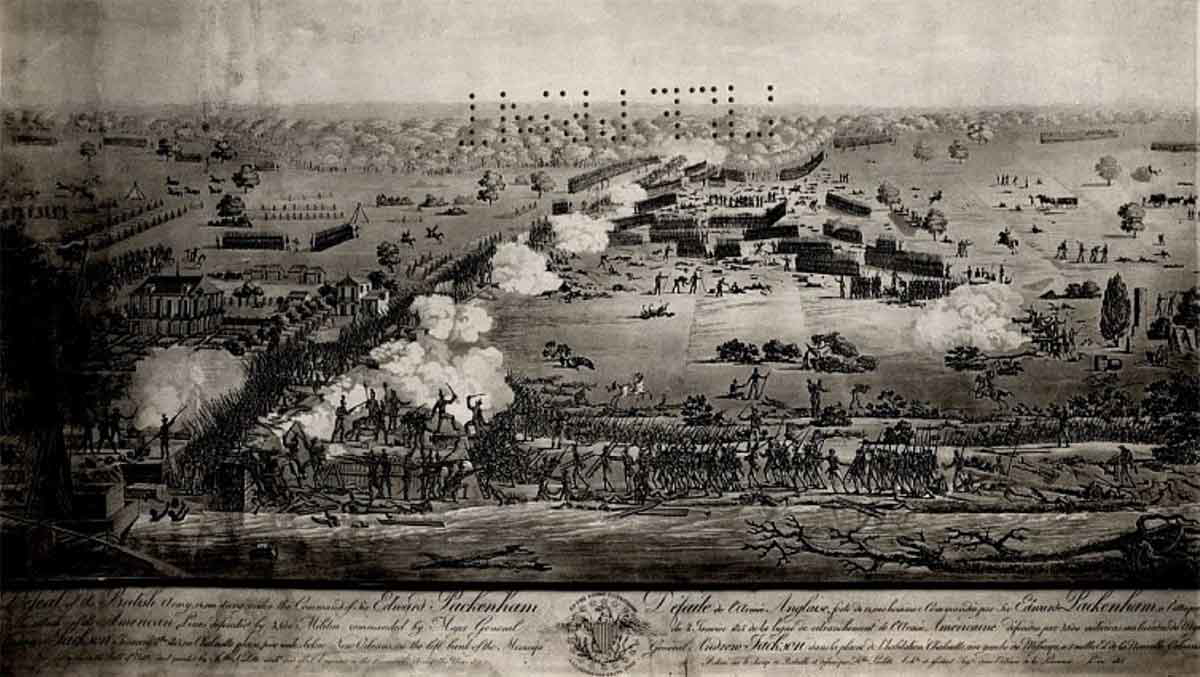

End of the War

Field artillery enabled a commanding American victory in the final battle of the War of 1812, the Battle of New Orleans in January 1815. Although the United States and England signed the Treaty of Ghent in the previous month, the news had not yet reached the southern United States. Unaware of the agreement, General Andrew Jackson deployed his artillery parallel to the Rodriguez Canal, known as “Line Jackson,” to deliver a decisive blow to the British. Coupling cannon assets strategically alongside key terrain allowed the United States to achieve undeniable victory against the British, dispelling their decades-long rival for good.

On water, American vessels repelled British assaults near New Orleans for weeks leading up to the battle. A small flotilla defended against enemy approaches via Lake Borgne. The USS Carolina similarly played an essential role in General Jackson’s initial assault on the British encampment at Villere Plantation, further signaling the future president’s nighttime assault through timed bombardment. While the USS Carolina was ultimately destroyed, its guns paved the way for the final British defeat.

The Rockets’ Red Glare

The effects of artillery during the War of 1812 are undeniable, and the weapon’s presence is forever memorialized in the national anthem of the United States. Surviving a 25-hour bombardment of Fort McHenry by British ships during the Battle of Baltimore, the young lawyer Francis Scott Key reflected on his experiences. Despite an initial hesitation to support the conflict due to his belief that war would cripple the young nation, Key served as the quartermaster of the Georgetown Light Field Artillery. As with any artillery unit, coordinating logistics and supplies for this unit was paramount in determining the readiness of the war’s most destructive asset.

As the British continued their naval bombardment, American gunners returned fire from the coastal artillery pieces. With the streaming trails of the Congreve rockets illuminating the night sky, Key could see the Stars and Stripes flying defiantly during the attack. Key recorded his experiences in a poem that reflected upon the effect of the “rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air.” Set to the tune of “To Anacreon in Heaven,” a popular English drinking song, “The Star-Spangled Banner” gradually gained popularity as an unofficial national anthem during the Mexican-American War and the Civil War. In 1931, President Herbert Hoover officially designated Key’s poem as the United States’ national anthem. A defining weapon of the time, the artillery of the War of 1812 echoes through this patriotic hymn.

Legacy

Aside from being memorialized in the national anthem, artillery from the War of 1812 had an impact on American military strategy for several decades. As the first war fought by the nascent US Army, the tactics and techniques developed during the War of 1812 would go on to define the US military’s offensive and defensive doctrine during the Mexican-American War and the Civil War.

Less than a decade after the War of 1812, the United States introduced the Monroe Doctrine, in which the American government threatened war with European powers seeking colonization or political interference in the Americas. Without a powerful standing army supported by effective artillery assets developed during the War of 1812, the Monroe Doctrine would have stood as an empty threat towards the European powers.

US artillery had played a decisive role in several victorious American battles at land and sea during the War of 1812, and would continue to serve as an important asset for American national security in the decades following the conflict.