summary

- Ancient Greek writing had no spaces, punctuation, or lowercase letters.

- Scriptio continua was efficient and suited oral reading traditions—but it required expert readers.

- Readers used grammar, rhythm, and context to parse meaning.

- Word separation evolved later to support broader literacy.

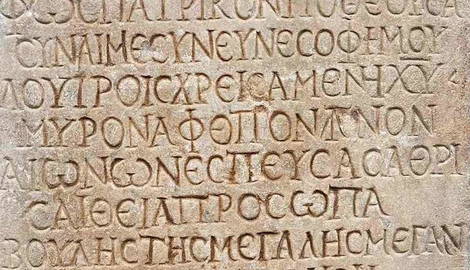

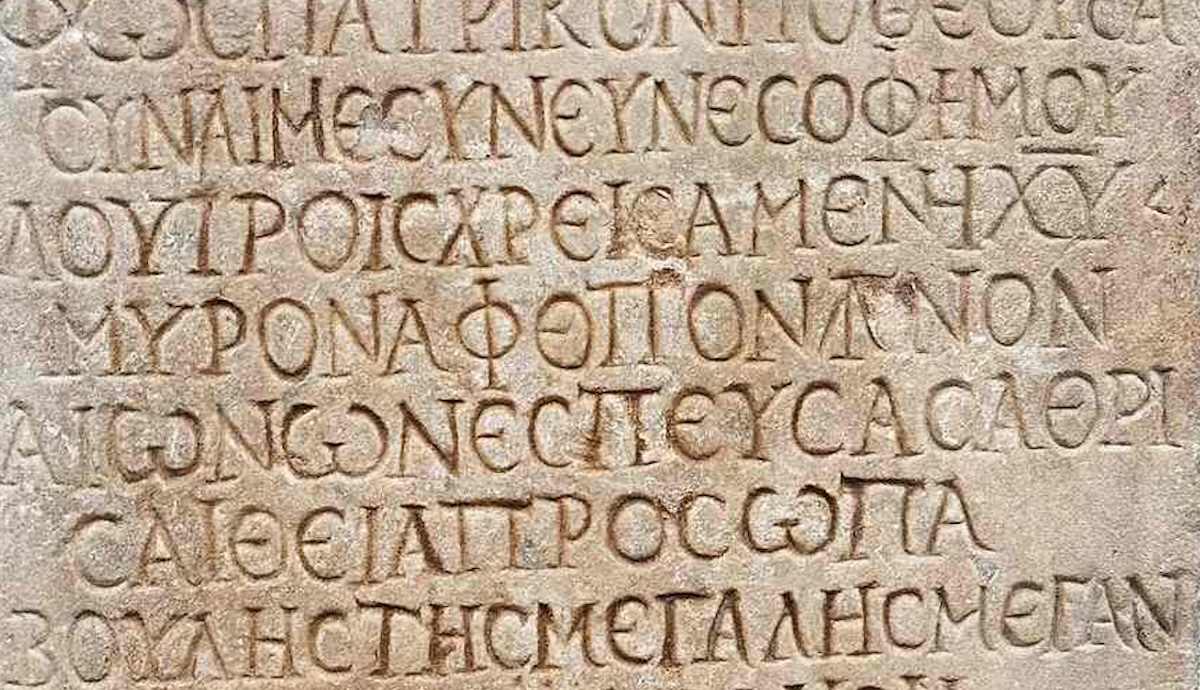

To modern eyes, ancient Greek writing looks like an impenetrable code—an unbroken wall of capital letters across stone or parchment without a single space or discernible punctuation mark.

This format is called scriptio continua, Latin for “continuous script.” There is no spacing, no punctuation, and no lowercase letters in scriptio continua. This was no mistake—it was the standard way of writing in the ancient Greek world. Stone inscriptions, papyrus scrolls, and sacred texts followed this format for centuries.

But why did the ancient Greeks write like this? And how did they manage to understand the text?

Why Ancient Greeks Wrote in Scriptio Continua

The reasons behind scriptio continua were practical, linguistic, and cultural.

- First, writing materials like papyrus and parchment were expensive in ancient Greece. A manuscript written in continuous script was significantly shorter and cheaper than one with visual breaks between words.

- Second, the structure of the Greek language facilitated the scriptio continua method. With its rich system of inflections—changes to word endings and prefixes—the Greek language naturally included grammatical clues that helped readers identify where one word ends and another begins.

- Finally, the act of reading itself was different in the ancient world compared to today. Reading was typically done aloud, either in private or to an audience. In this context, visual spacing was less critical. Trained readers relied on sound—including intonation, rhythm, and phrasing—to bring clarity to the continuous stream of text.

How Ancient Readers Navigated the Continuous Stream

Parsing scriptio continua was an expert skill developed over years of practice. And it was less about visual scanning and more about rhythm, memory, and flow. In ancient Greece, reading was a physical, performative act. Texts were typically read aloud, whether to an audience or in a hushed voice alone. This vocal engagement helped bring meaning to the stream of letters. Familiar phrases, poetic meters, and grammatical cues all guided the voice and the ear toward comprehension.

From a young age, students practiced reading scriptio continua through repetition and recitation. Over time, trained readers developed an intuitive sense of where words began and ended, even in complex passages. Expert readers, especially scribes, priests, and rhetoricians, became so adept that they could scan and interpret these texts with seeming effortlessness. On rare occasions, scribes inserted aids into the written text, such as the hypodiastole, a small mark used to clarify ambiguous boundaries between letters. But “punctuation” primarily came from the reader’s own cadence, honed through experience.

The Transition Away from Scriptio Continua

Naturally, writing practices evolved over the centuries. Around the 7th to 8th centuries CE, Irish and Anglo-Saxon scribes began experimenting with spacing between Greek words to support the emerging practice of silent reading. In the Byzantine world, a major shift occurred in the 9th century with the rise of minuscule script—a new handwriting style that introduced lowercase letters, punctuation, and eventually word separation. These innovations made texts easier to navigate at a glance.

So why did scriptio continua fall out of favor? The change was driven not just by scribes, but by readers. Literacy began to expand beyond the elite, and silent, individual reading became more common. Unlike trained performers reading aloud, silent readers needed visual cues—spaces, punctuation, and structure—to interpret the text internally. The format that had once suited the rhythms of speech no longer supported the cognitive demands of silent comprehension.

As reading shifted from a communal, oral activity to a private, visual one, the demands of silent literacy rendered scriptio continua increasingly impractical, prompting the gradual adoption of more reader-friendly formats.