19th-century Europe was heavily focused on colonization as a means to bolster the power of empires. Africa was in the spotlight for its potential wealth and resources, and the race was on. By 1914, there were only two countries not controlled by a European entity. King Leopold II of Belgium wanted a piece of the action, not for the benefit of his people, but to boost his own power. The lengths he went to secure his wealth and status were incredibly shocking, and many of his actions wouldn’t be revealed until after the fact. Leopold’s impact shaped the future of the Congo and resonates in his legacy today.

1. Leopold’s Piece of the Scramble

From an early age, the man who would become Leopold II of Belgium seemed obsessed with the idea of gaining colonies. Belgium lacked a trading fleet and navy, and as a result, few royals or nobles shared young Leopold’s interests. When he ascended the throne in 1865 at age 30, his desire for colonies only seemed to increase. He observed other European powers enjoying the fruits of their conquests and even attempted to purchase colonies from other countries. When these attempts failed, his interests turned to Africa. Disguising his true intentions by proclaiming he wanted to make an impact on slavery prevention, Leopold created organizations such as the International Association of the Congo, which helped him gain legitimacy and funds from across Europe.

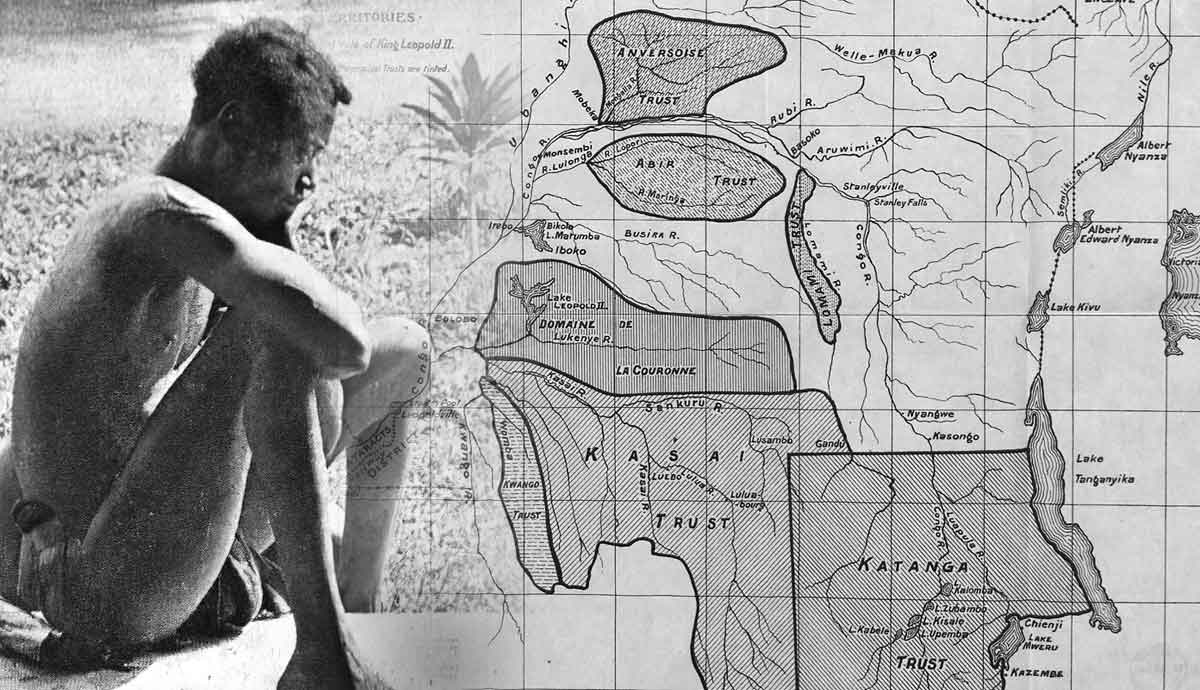

By 1885, Leopold had control of the Congo, a heavily forested area located in the center of the African continent. However, rather than operating the region as a colony, Leopold had organized it so that he had sole control as a private owner. He retained control for about fifteen years until reformers finally brought sufficient public attention to the devastation in the Congo at Leopold’s hands. In 1908, control of the region was transferred to the Belgian government.

2. The Congo Was Leopold’s Personal Possession

Leopold stated publicly that his goals were to prevent the Arab slave trade and bring “civilization” to the people of the Congo. Instead, he used funds that he borrowed from the Belgian government and supporters such as the Royal Geographic Society to build his overseas empire. While Leopold never visited his new dominion, he governed it in an autocratic fashion from home. With the ironic name of Etat Independant du Congo, the Congo Independent State or Congo Free State, Leopold put his new holding to work for him.

Despite his publicly voiced opposition to slavery, Leopold relied on the forced labor of the Congolese people to make him successful. By using these people, Leopold also exploited the region’s natural resources, particularly ivory and rubber. Raw goods were moved to the port city of Boma and shipped to Europe from there. It is estimated that Leopold pulled approximately 1.1 billion dollars from the Congo during his reign, according to today’s standards.

3. Bicycles Added to Leopold’s Success

Before automobiles were an easily accessible form of transportation, bicycles found their place in society as important modes of transportation. In the 1890s, the addition of rubber tires, creating a more comfortable ride, created a “bicycling boom.” Bicycles were more popular than ever all over the globe, and this surge in production required a key ingredient: rubber. Synthetic alternatives were yet to be invented, allowing rubber companies like Leopold’s to benefit from this demand. During the fifteen years that Leopold had possession of the Congo, approximately 75,000 tons of rubber were wrenched from the territory. However, the expense paid by the Congolese people for this production was grim.

4. Leopold Went to Great Lengths to Ensure Quotas

The lengths that Leopold’s regime went to in order to ensure their needs were met in the Congo resulted in some of the worst human rights violations in world history. Leopold’s rubber companies demanded that the local Congolese pay a tax in the form of rubber collection. Though gathering rubber was arduous work, people who did not meet these “tax” quotas would be punished, or their families would be, until the demand was met. A favorite punishment of Leopold’s forces was the amputation of limbs. In an effort to conserve bullets, sentries were required to provide a human hand for each bullet used. As a result, many sought to acquire a stockpile of preserved hands to account for their firearm usage. Since amputating the workers’ limbs would limit their ability to work, the severing was often done on family members, including children. Wives, elders, and children were held captive until certain quotas were met.

Another popular form of physical violence was the use of the chicotte, a whip made of hippopotamus leather that could cause devastating injury or death with prolonged use. Children were not spared from these punishments. One example came from a Belgian lawyer visiting the area, who told of every servant boy in a town receiving 50 chicotte lashes (25 usually led to unconsciousness) as a result of a small group of children accused of laughing at a white man. The true extent of the horrors that were undertaken by Leopold’s interests in the Congo may never be known. After the Congo was turned over to Belgium proper, the furnaces outside of Leopold’s palace burned materials relevant to the Congo. Leopold was reported as saying, “I will give them my Congo, but they have no right to know what I did there.”

5. He Had His Own Military Force

Since Leopold never visited the Congo, he relied on representatives to carry out his wishes and enforce his rules. One of these entities was the Force Publique, Leopold’s military representation in the Congo. These were the men responsible for ensuring quotas were met and doling out punishments. The Force was composed of European mercenaries, as well as Congolese men who had been pressed into service. Children were funneled into military training camps with the end goal of serving in the Force. While some members of the Force were African, all officers were white. At times, the Force numbered up to 19,000.

6. The Horrors Inspired Joseph Conrad

Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad is one of the most celebrated novels of the 20th century, still utilized today in studies of literature and humanity. What many don’t realize is that this examination of themes such as civilization and society is based on Conrad’s actual travels in the Congo in the late 19th century. Though outspoken criticism of the Congo wouldn’t be taken seriously until the first decade of the 20th century, Conrad was one of the first to disparage Leopold’s adventure. He called the colonization of the Congo a “rapacious and pitiless folly.” The main character, Marlow, serves as an alter ego to Conrad, who spent time in the Congo working on a steamer. Many of the sights described in the novel were reminiscent of observations Conrad made on his journeys. The villain of the story, Mr. Kurtz, was based on several individuals that Conrad met during this time in the Congo, including a Captain from the Force Publique and an ivory agent.

7. Leopold Is Defended Today

In an age where the memories of many historical heroes turned villains have been brought to justice, Leopold surprisingly still finds defenders nearly a century after his death and with the revelation of his crimes in the Congo. At least 13 statues in Belgium representing Leopold exist, and several parks, public areas, and streets are named for the king. In 2010, Louis Michel, former Belgian foreign minister, stated that King Leopold II was “a hero with ambitions…”. In 2020, the younger brother of Belgium’s king, a descendant of Leopold, was scrutinized for stating that Leopold was not responsible for the atrocities in the Congo since he never visited the territory. Also in 2020, the former president of the Free University of Brussels argued that colonization such as that undertaken by Leopold in the Congo had “positive aspects.”

Despite his modern-day supporters, Leopold’s actions were publicly condemned by European leaders, many of whom also participated in the colonization of Africa. The discussion of his legacy continues today, with some calling for the removal of statues and a more honest discussion about the events that took place in Leopold’s Congo.

Recommended Reading:

Hochschild, Adam (1998). King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. First Mariner Books.