Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire during the 4th century CE. The empire fell in the next century as barbarian hordes, such as the Visigoths, Vandals, Ostrogoths, Huns, Franks, and Alemanni, invaded and conquered parts of their territory. Rome, which was still a flourishing city in 400 CE, lay in tatters a hundred years later in the sixth century and saw the start of the Middle Ages, also called the Dark Ages. Yet, the spread of Christianity continued even in that period, despite serious challenges.

The State of Europe

Europe was in a state of upheaval as the Middle Ages commenced. Invasions by Barbarian hordes ushered in the fall of the Roman Empire, plagues and pandemics vanquished the population, and the emperors of the Eastern Roman Empire did not do enough to support and assist the people of the fallen Western Empire in their daily struggles. The barbarian hordes also brought paganism into direct confrontation with Christianity.

Methods of Missions and Evangelism

Numerous factors contributed to the spread of Christianity during the Middle Ages. These were not always aspects of life we would consider as significant from our perspective, though they had a major impact during the Dark Ages.

Political Alliances and Royal Conversions

Political leaders during the Middle Ages often adopted Christianity for political and cultural reasons. Some would also force Christianity on those within their realm, resulting in mass conversions albeit in name and not necessarily in belief. Among them are King Clovis I (converted) of the Franks and Charlemagne (converted others). These rulers would construct monasteries and churches in their realms to show their allegiance to the Church.

At the height of papal power, the Roman See was a political powerhouse as much as it was a church. The Pope was instrumental in installing many-a-king, and the Holy Roman Empire was nothing other than an attempt to revive the Western Roman Empire within a Christian framework. The lines between Church and State blurred for the most part and resulted in religious persecution of those who opposed the teachings or will of the Church. Politicians and royalty often bowed to the powers in Rome and enforced Christianity on their people.

Monasteries

Munks and Nuns in monasteries preserved and copied religious texts, and these institutions often became centers of learning from which the Christian faith spread. In some instances, monasteries were the only option the general population had in order to become literate. The texts used to teach pupils literacy were those that spread the Christian faith.

Orders like the Benedictines and later the Cistercians established monasteries throughout Europe, spreading Christian teachings. Monasteries also cared for the sick or injured which garnered goodwill toward Christianity and provided opportunities for evangelism to take place.

Education and Scholarship

The Church established Cathedral schools and universities to become hubs of learning and scholarship. A significant part of the curricula of these educational centers focused on Christian doctrine. Institutions taught the works of notable Christian scholars and distributed them among students and the doctrine they espoused spread throughout Europe. The clergy and nobles trained at these institutions used their influence to disseminate their views among those within their spheres of influence.

Integration of Local Cultures

Rather than oppose every aspect of paganism, Christian missionaries would at times integrate local culture into Christian practice. Pagan holidays like Yule and Samhain were incorporated into Christian celebrations like Christmas and All Saints’ Day, while local heroes were adopted as saints to entice pagans to accept the Christianization process.

Crusades

Forced conversion was another questionable method of spreading the Christian faith into newly conquered areas. How well this method worked towards real conversion is doubtful. Holy wars saw Christian expansions in the Iberian Peninsula and Eastern Europe. At times, missionaries accompanied Crusaders to work with the local population to convert them of their own volition, but history also bears witness to forced conversions.

Religious Art and Architecture

Richly decorated cathedrals and churches sprang up all over Europe. Some of them were decorated with Christian art like murals and statues depicting Biblical narratives. Though these works of art were not as elaborate as those produced during the Reformation, Renaissance, and Enlightenment periods they nonetheless served as tools to bring the Bible message to those who saw them and heard the associated stories. These works of art became tools of evangelism to the illiterate and literate alike.

Economic and Social Influence

During parts of the Middle Ages, the Church flourished, owning vast swaths of land and many mansions and opulently decorated structures. These riches appealed to many who sought to benefit by aligning themselves with the Church. The potential for gaining higher status in society often went together with being in the good graces of the local clergy and upper echelons of the Church-State bureaucracy.

The Church also developed several social services that provided care to the general populace such as orphanages and hospitals. These institutions attracted the poor and frail, offering relief from their suffering. Many converted as they benefitted from the services these institutions offered.

Significant Missions: Gregory the Great (c. 540-604)

Gregory the Great, who served as pope from 590 to 604, was the first to provide a significant sense of stability in Rome and drew people back to the Church as a beacon of hope amid the turmoil of a plague. He was a formidable servant-leader who not only cared for the people by providing for their daily needs for food and shelter, but he also used the contacts and influence he held outside of Rome to assist the populace of his city, and to increase the influence of Rome in other city-states across Europe.

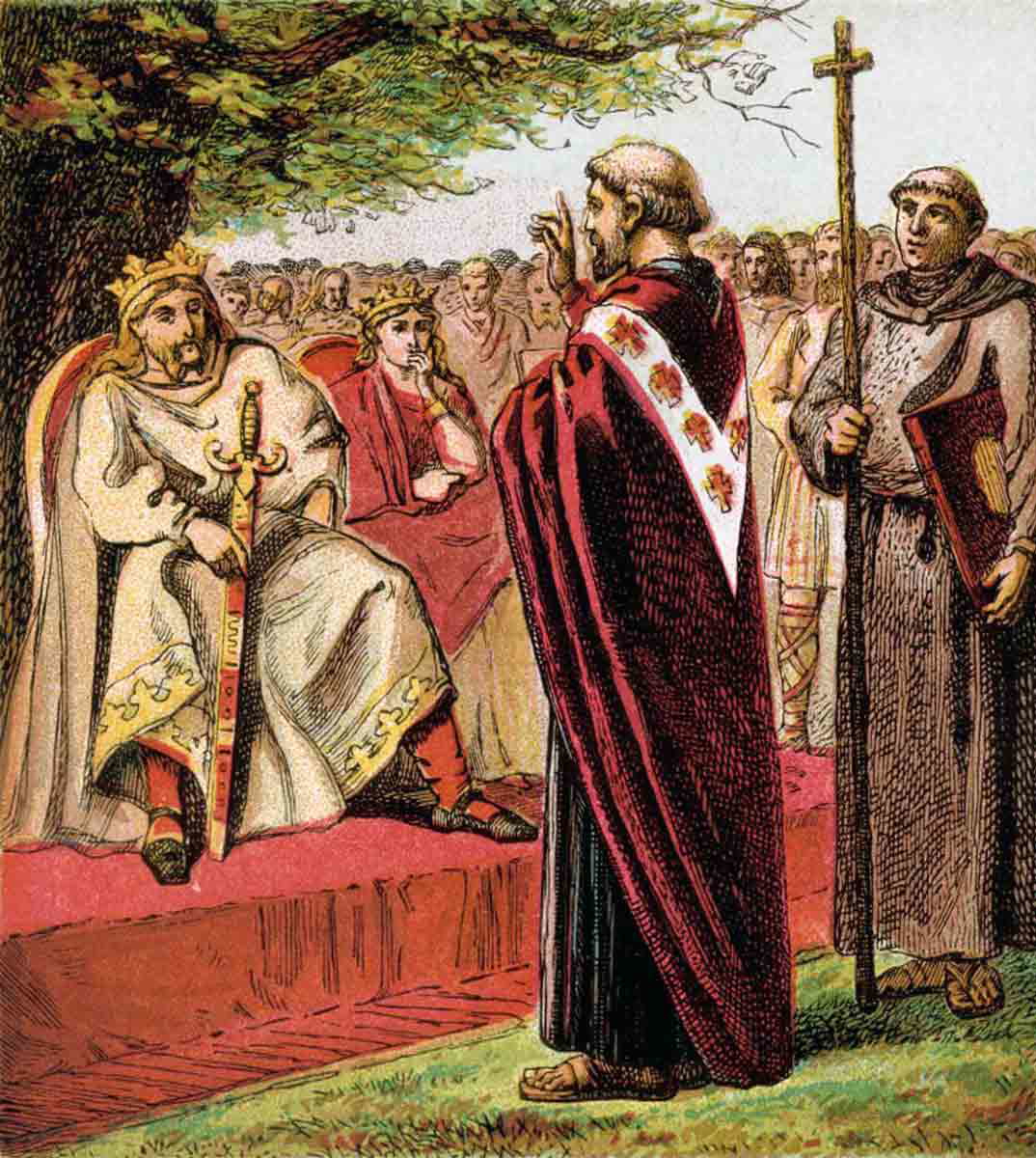

Saint Augustine (d. 604)

A particular passion of Gregory’s was the evangelism of Britain. He was the impetus behind the missionary efforts by Augustine of Canterbury who he sent to the island to do evangelism. As a staunch supporter of monasticism, which he practiced and expanded himself before becoming pope himself, Gregory encouraged the lifestyle for the spiritual benefits it held. As centers of learning, monasteries contributed to the education of the people and were institutions of theological training and hubs for evangelism.

Saint Boniface (c. 675-754)

History remembers Saint Boniface as a notable missionary to the Anglo-Saxons who resided in Germany and the Netherlands. He contributed to structuring the Church into bishoprics, monasteries, and dioceses in these parts of Europe and was instrumental in establishing Mainz as a diocese which later became an important ecclesiastical center.

The German people, who were staunch pagans, were not easy to convert. The Hessian tribes who occupied territory in modern-day central Germany worshiped Donar, the god of thunder (the German equivalent of the Norse god Thor). The Donar Oak was a tree they believed was under his protection. It was a site where worshipers gathered, held rituals, and sacrificed. It served as a symbol of resistance against Christianity. Harming the tree would evoke divine retribution, they believed.

Boniface traveled to Germany and promptly fell the oak while many pagan onlookers gathered to observe what would happen. No ill effect or sign of retribution befell Boniface. Many pagans converted to Christianity since they considered the event proof that their former pagan god was powerless in the face of the Christian message. Though some historians regard the record of the Donar Oak as a myth, it has served as an inspiration to many missionaries since. Saint Boniface has a legacy as a fearless missionary who did not shy away from evangelizing pagan people in foreign lands.

Saints Cyril (827-869) and Methodius (815-885)

These two brothers hailed from Thessalonica. They ministered to the Slavic people of Central and Eastern Europe, going as far as to develop the Glagolitic alphabet to provide the Slavic people with a translation of the Bible in their native tongue. They also encouraged natives to worship in their first language, rather than using Latin. The act made Christianity more accessible to the Slavic people. Their missionary work influenced cultural and religious development among Slavic nations and their missionary work is recognized in the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic traditions.

Ansgar (801-865)

Ansgar’s missionary endeavors to the Scandinavian peoples, particularly in Denmark and Sweden earned him the title “Apostle of the North.” Though he faced significant opposition when spreading Christianity in Denmark and establishing the first Christian Church in Sweden, his work paved the way for large-scale conversions in later centuries.

These men are but a sample of the many who could be highlighted for their contribution to spreading Christianity during the Middle Ages.