We usually think of the Vikings sailing out of their Scandinavian homes to the British Isles, where they pillaged, stole, and massacred the local inhabitants. But in 1002 CE, the English turned the tables on the Vikings with a historic massacre known as the St Brice’s Day Massacre. Frustrated with recent events, King Aethelred ordered the deaths of “all the Danes in England.” But how successful were the Anglo-Saxons in dealing with the Viking threat?

How Did the Danes Get to England?

The Vikings started to raid English shores in the last decade of the 8th century. When they raided Lindisfarne in 793 CE, they found a coastal monastery that was undefended and full of valuable treasures, including educated monks that could be sold as slaves. Soon, they discovered similarly vulnerable and lucrative targets, and their raids became increasingly frequent. These raids were principally but not exclusively conducted by Vikings from Denmark, so they were collectively known as Danes to the English.

The small but frequent Viking raiding parties were an ongoing problem for the Anglo-Saxons living in England, but things became more serious when a large and coordinated Viking army landed in 865 CE. Known as the Great Heathen Army, they ostensibly arrived to avenge the death of Ragnar Lodbrok. However, the evidence suggests that they landed with families and supplies. They were looking to seize fertile lands for their own use.

The Vikings established a base at York, possibly under the leadership of Ivar the Boneless, and then conquered and occupied large swathes of Northumbria, East Anglia, and Mercia until only the Kingdom of Wessex resisted. Following years of conflict, a Wessex victory at the Battle of Edington in 878 CE gave King Alfred the Great of Wessex the leverage he needed to bring the Vikings to the treaty table.

Nevertheless, it was the Anglo-Saxons who made significant concessions. A boundary was created between Anglo-Saxon lands, mostly in Wessex, and what was now considered territory under Viking rule to the north of that border. This territory was more-or-less given to the Vikings to be governed by them under “Danelaw.” However, the treaty also agreed to a price to be paid for the wanton slaying of either Englishmen or Danes by the other side.

This treaty only stood for around 50 years, as both sides continued to menace each other. But even as Erik Bloodaxe was driven out of York in 954, and Aethelflaed, the Lady of the Mercians, retook land, many Vikings remained in England, living relatively peacefully, with Danish jarls submitting to Anglo-Saxon rule.

A Renewed Viking Menace

After several generations of relatively peaceful cohabitation, Viking raids intensified again in the 980s. These were conducted by external Vikings who were not settled in England. This was around the same time Iceland was settled by Norwegian Vikings fleeing oppressive rule at home by Harald Fairhair. A similar consolidation of power in the hands of fewer, more powerful leaders may also have encouraged increased raiding activity in England.

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the future Norwegian king Olaf Tryggvason landed in England with 91 ships in 991 CE, resulting in the Battle of Maldon, a devastating defeat for the Anglo-Saxons. The English King Aethelred the Unready was convinced to pay the Vikings off with a bribe that would become known as Danegeld. He reportedly paid 10,000 Roman pounds of silver, which is around 3,300 kilograms or 7,275 lbs.

This act inspired the much later Rudyard Kipling poem, Danegeld, in which he warns, “Once you have paid him the Danegeld, you never get rid of the Dane,” as the Vikings returned year after year to collect their tribute in return for not attacking.

The Vikings seem to have been particularly heavy-handed in 1001, raiding through southern England and burning villages indiscriminately as they traveled. While Aethelred paid his Danegeld in 1001, by 1002, he seems to have had enough.

Aethelred Orders the Massacre of the Danes

By 1002, Aethelred finally realized that his strategy of paying ransom was not working, and he chose to take drastic action. On 13 November 1002, St Brice’s Day, he ordered his army to slay all the Danes in England. It is unclear what exactly he meant by “all the Danes.” Did he mean just raiders and Viking mercenaries that he himself had hired from the raiding parties, Danes that had recently settled in Wessex territory, or Anglo-Danes beyond the old Danelaw border, many of whom had been established in England for generations? Was it just men, or also women and children?

Archaeological evidence related to the massacre has been found at Oxford and Ridgeway Hill in the south, which suggests that the move was focused on male Danes in Wessex, but a mix of established settlers and new invaders.

The most concrete evidence we have for the massacre comes from Oxford. Firstly, a royal charter from 1004 CE remarks on the “most just extermination” of the Vikings in Oxford. It describes how those targeted tried to take shelter in the church. When the Anglo-Saxons were unable to dislodge them, they burned the church with them inside. The writer notes that it is with God’s aid that he is currently rebuilding that very church.

In 2008, archaeological investigations at St John’s College discovered the bodies of 37 people who had been massacred. Researchers believe these bodies belonged to the Vikings who hid in the church on St Brice’s Day.

The bodies include 35 males between the ages of 16 and 25 and two children of unknown gender. Many of the bodies show signs of old wounds that have healed, suggesting that they were warriors. Chemical analysis suggests that the bodies were of Norse origin and that they died between 960 and 1020 CE. The absence of women may reflect the fact that the Viking arrivals married local Anglo-Saxon women.

Notably, the bodies are unarmed and show no defensive wounds. In addition, the death wounds they received were mostly from the back, suggesting that they were attacked while fleeing. This fits the scenario of the English soldiers falling on them unexpectedly and the victims then fleeing into or away from the burning church.

A group of 54 bodies found at Ridgeway Hill probably also relate to the St Brice’s Day Massacre. Ridgeway Hill is in the south of England in an area heavily targeted by the Vikings in the preceding decade and was a likely location for settlement.

The mass grave contains 54 male bodies, which isotope analysis suggests belonged to Vikings and date to 970-1030 CE. All the bodies were beheaded, with the heads and bodies separated in the burial. Notably, three heads are missing, suggesting they may have belonged to important Vikings and were kept as trophies or proof of death.

Viking Revenge

While Aethelred the Unready seemed satisfied with his brutal work in his 1004 charter, it would prove to be another misstep. According to tradition, Gunnhilde, the sister of Sweyn Forkbeard, then the king of Denmark and Norway, was killed in the massacre along with her husband Pallig Tokesen. This may have given him the justification he needed to launch an aggressive assault on England. He also clearly had financial gain in mind as before launching his attack, he made arrangements to sell spoils from his planned raids to the Duke of Normandy, the father of Emma of Normandy, whom Aethelred married in 1002.

Whatever his motivations, Sweyn Forkbeard led waves of invasions and pillaging across Aethelred’s territory. His first series of raids was between 1003 and 1007, and he is known to have visited Oxford, suggesting that revenge was at least one of his purposes. In 1007, he was paid 36,000 pounds of silver to leave.

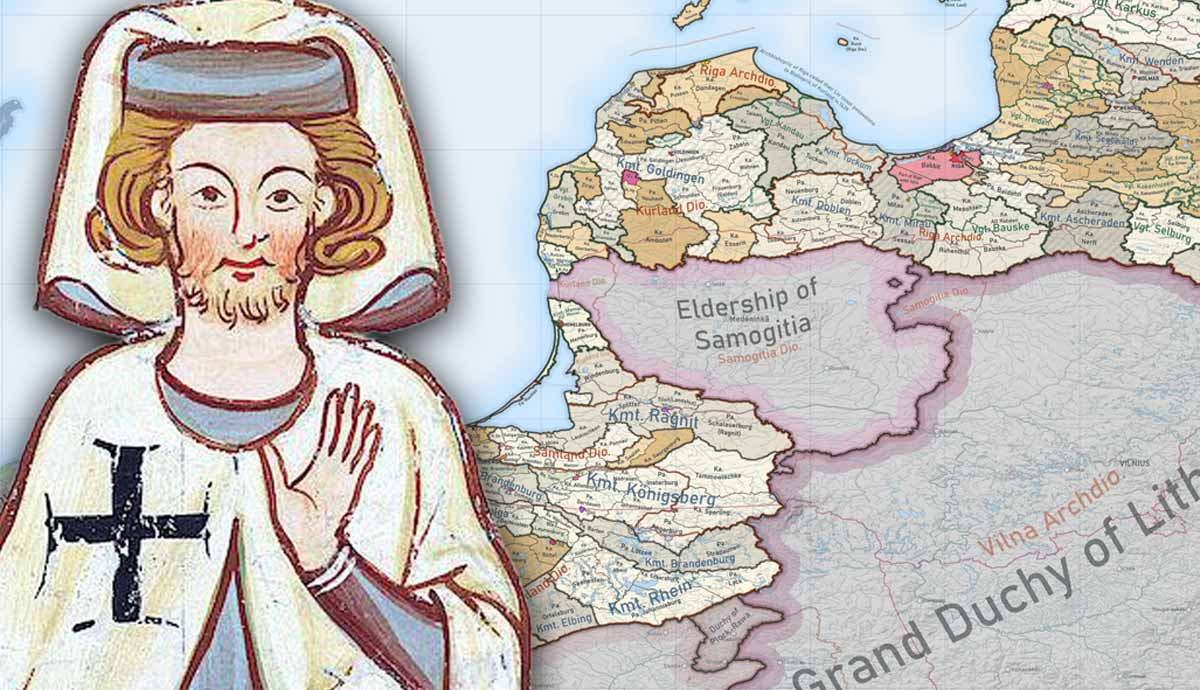

The next raids happened between 1009 and 1012 and involved the Jomsvikings. This was an elite order of Viking mercenaries working out of a stronghold in northern Poland. They had strict rules for joining, including age and the recommendation of an existing member of the order. Once a member, they swore off women while also swearing loyalty to the order and never surrendering. While in England, they are said to have plundered and burned Canterbury Cathedral. They were paid off with 48,000 pounds of treasure in 1112.

In 1113, Sweyn Forkbeard took advantage of Aethelred’s increasing weakness and launched a full-scale assault. He quickly forced Aethelred and his two sons into exile and made himself the king of England. He died just five weeks later in early 1014 and was succeeded by his son Cnut. While Aethelred and his sons would fight back, by 1019, Cnut was in full control of England, as well as Denmark, Norway, parts of Sweden, Pomerania, and Schleswig, making him Cnut the Great.

However, Cnut also married Aethelred’s widow, Emma of Normandy, and was succeeded by his son with her, Harthacnut. But when he died in 1042, his half-brother Edward the Confessor, the son of Aethelred and Emma, was called to England as its new king. Thus, the territory taken from Aethelred by the Vikings in vengeance was returned to his son.

Consequences of the St Brice’s Day Massacre

While this might be a rather anticlimactic ending to the story, the massacre was seen by one side as the English finally fighting back against ruthless raiders and by the other side as the English proving themselves just as brutal as the rapidly Christianizing heathens they criticized.

The aftermath of the massacre would also put in motion the events that would lead to the Norman Conquest in 1066. Edward the Confessor was childless and seems to have used the promise of succession as a negotiating tactic. He promised succession to his brother-in-law Harold Godwinson, an important Anglo-Saxon nobleman, William the Duke of Normandy, and Harald Hardrada, king of Norway.

When Edward died in 1066, he was succeeded by Godwinson. The new English king had to face attacks from Hardrada in the north, which he won, but which weakened his defenses against William in the south, resulting in the Norman Conquest.