Sufism began as an ascetic and mystical movement in the early centuries of Islam. However, over the centuries, the movement developed into an intricate system of philosophy, ethics, and practices that Muslims could follow to experience the fullest depth of the Prophet Muhammad’s teachings.

Initially limited to small circles of students guided by a saintly Muslim mystic, these saintly personalities established spiritual communities and brotherhoods that allowed Sufism to proliferate across the Islamic and non-Islamic world. These Sufi orders carried immense power among the people, often drawing the ire of rulers and other vested interests due to their influence. Sufi orders, and five in particular, drove Islamic history—from the Ottoman Empire to the Mughal Empire, from Cairo to Baghdad, and from Timbuktu to Seville.

Sufi Disorder

Any notion of order arises out of relative disorder, and the Sufi orders are no different in this respect. Before these mystical brotherhoods arose and organized, mystically inclined Muslim sages in the first few centuries following the Prophet Muhammad (d. 632) were often either nomadic or hermetic scholars, often living on the fringes of society both physically and socially. Examples include famous Sufi saints such as Abu Yazid al-Bistami (d. 874), Ibrahim ibn Adham (d. 777), and Mansur al-Hallaj (d. 922).

Many such individuals were known for their flouting of social norms and ecstatic outpourings, often to the vexation of orthodox Muslim scholars. However, others were themselves among the scholars, as Sufism is, in its essence, entirely complementary to Islamic scholarship—in fact, Sufis would often define their path as the fruit of true understanding and implementation of shariah. These Sufis, which included the likes of Junayd al-Baghdadi (d. 910), Abu al-Qasim al-Qushayri (d. 1072), and Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami (d. 1021), lived something of a double life—scholars by day and mystics by night, sharing the most sanctified of teachings only with those students who were ready and worthy enough to receive them.

Despite no formal Sufi orders being formed at this point—at least not in the sense that they would later be organized—these Sufi mystics shared a common spiritual lineage and ancestry that would be integral to the formation and identity of later Sufi orders. Each shaykh endowed with the permission to transmit spiritual knowledge had received it from a shaykh of their own, with each chain of transmission stemming from the single origin point of the Prophet Muhammad.

For many Sufi orders, the chain of transmission would be common for several generations, often being traced through the Prophet’s cousin and son-in-law, Ali ibn Abu Talib (d. 661), then through Ali’s sons, Hassan (d. 669), and Hussein (d. 680), before branching off into others.

Arguably, the first Sufi order to form, and through which almost every subsequent Sufi order finds its beginnings, centers around the legendary and charismatic character of a Sufi shaykh known for both his grounding in Islamic scholarship and his awe-inspiring miracles and spiritual impact on the hearts of thousands.

1. The Qadriyya and the Rose of Baghdad

Abd al-Qadir Jilani (d. 1166) hailed from a pious family in Jilan, located in modern-day Iran along the Caspian Sea. After a series of visionary experiences, and with his mother’s permission and blessings, Abd al-Qadir set off toward Baghdad in his early teenage years in pursuit of religious and spiritual knowledge. Upon arriving, he came under the tutelage of the renowned Abu al-Khair al-Dabbas who saw in him great potential to master the spiritual sciences of the Sufis.

Much given to devotions, he spent years in the wilderness outside of Baghdad, committed to long periods of austerities, fasting, and seclusion. Eventually, however, he was prompted to return to society to live amongst and guide the people both as a scholar and a mystic, as was the way of the Prophet Muhammad.

Abd al-Qadir soon garnered an immense following, and his endless discourses were renowned for moving hundreds or thousands of listeners to tears, inspiring conversions to Islam, and sometimes even causing listeners to die from ecstasy. Nonetheless, Abd al-Qadir’s path was one of sobriety in the way of al-Junayd, to whom he was connected through his chain of teachers. His teachings were fully grounded in orthodox Islam, and a central tenet of the Qadriyya, and by extension, all later Sufi orders, was that the shariah served as a vehicle and channeling force for the spiritual ecstasy experienced by the mystical devotee. Thus, the two were not only harmonious but inextricably essential for one to come to human perfection.

Shaykh Abd al-Qadir was noted to have 40 children who, along with other non-consanguinous disciples, inherited his spiritual authority and continued their own branches of the Sufi lineage. The Qadriyya Order is arguably the most widespread across Islamic society, partly because of its essential and foundational approach to Sufism as the inner dimension of Islamic practice. It is perhaps for this reason that Shaykh Abdul Qadir Jilani, and the Qadriyya in general, are among the most widely accepted and embraced Sufi Orders throughout the Islamic world, being something of an essential form of the tradition free from the cultural distinctions that would characterize several Sufi orders discussed below.

The Qadriyya would form the foundation of both Sufi-Sunni revival movements, such as the massive Barelvi movement founded by Ahmad Raza Khan (d. 1921) in the Indian Subcontinent, while also being the chosen order of the renowned and somewhat controversial Salafi scholar, Ibn Taymiyyah (d. 1328), who was known for his sharp criticism and polemics toward many Sufi practices.

2. The Naqshbandi and the Golden Chain

While every Sufi order traces the origin of its lineage to the Prophet Muhammad, only one order does not trace its subsequent lineage through the Prophet’s cousin and son-in-law, Ali ibn Abu Talib. The Naqshbandis, as they are now known, traced their lineage through the Prophet Muhammad’s closest friend and first Rashidun Caliph, Abu Bakr as-Siddiq (d. 634).

Many of the subsequent masters of the lineage would nonetheless appear in the lineages of other orders, but the Naqshbandis’ unique origins imprinted a distinctive character to this order’s practices. Abu Bakr was known for his truthfulness, gentleness, and reserved demeanor. As the Prophet Muhammad said of him, “Abu Bakr does not precede you because of much prayer or fasting, but because of a secret that is in his heart.” It is this secret that the Naqshbandis lay claim to receiving and upholding since his time.

This order arose predominantly around the cultural and economic centers of Central Asia, such as the cities of Balkh in present-day Afghanistan or Samarkand and Bukhara in present-day Uzbekistan. It is in Bukhara that the patron saint and namesake of the Naqshbandi order, Baha al-Din Naqshband (d. 1389), lived and taught.

Aside from assiduously following the inner and outer mandates of the Islamic Law, Sufi orders are largely distinguished by their varying methods of remembering God, or dhikr Allah. And unlike most other orders that take part in some kind of rhythmic chanting of God’s names, the Naqshbandis partake in a silent, inner dhikr.

It is this more internal orientation that allowed the Naqshbandis to flourish and persist within various political and social upheavals throughout history. Whether it was under the genocidal invasions of the Mongol Empire (c. 1206-1368), the repressive government of the Soviet Union (c. 1922-1991), or the outright prohibition of Sufi Orders instituted by Turkiye’s founder, Kemal Ataturk (d. 1938), the Naqshbandis continued to meet in secret, transmitting their teachings and knowledge.

The Naqshbandis would nonetheless gain favor among Ottoman sultans and Mughal princes alike. Figures such as Imam Shamil (d. 1871) brought a certain revolutionary spirit to the Naqshbandi way, known as a fearless freedom fighter during the Russian invasions of Daghestan. Another branch of the Naqshbandis with roots in the Daghestan region became perhaps the most widespread and publicly prominent Sufi groups of the 20th and 21st centuries, headed by the revered Shaykh Nazim al-Haqqani (d. 2014) who actively taught in both the Western and Islamic world for decades.

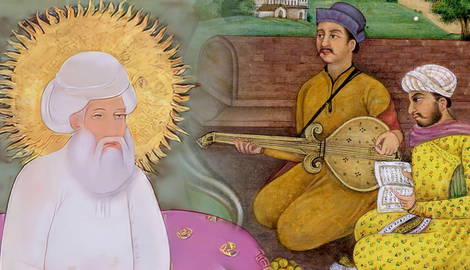

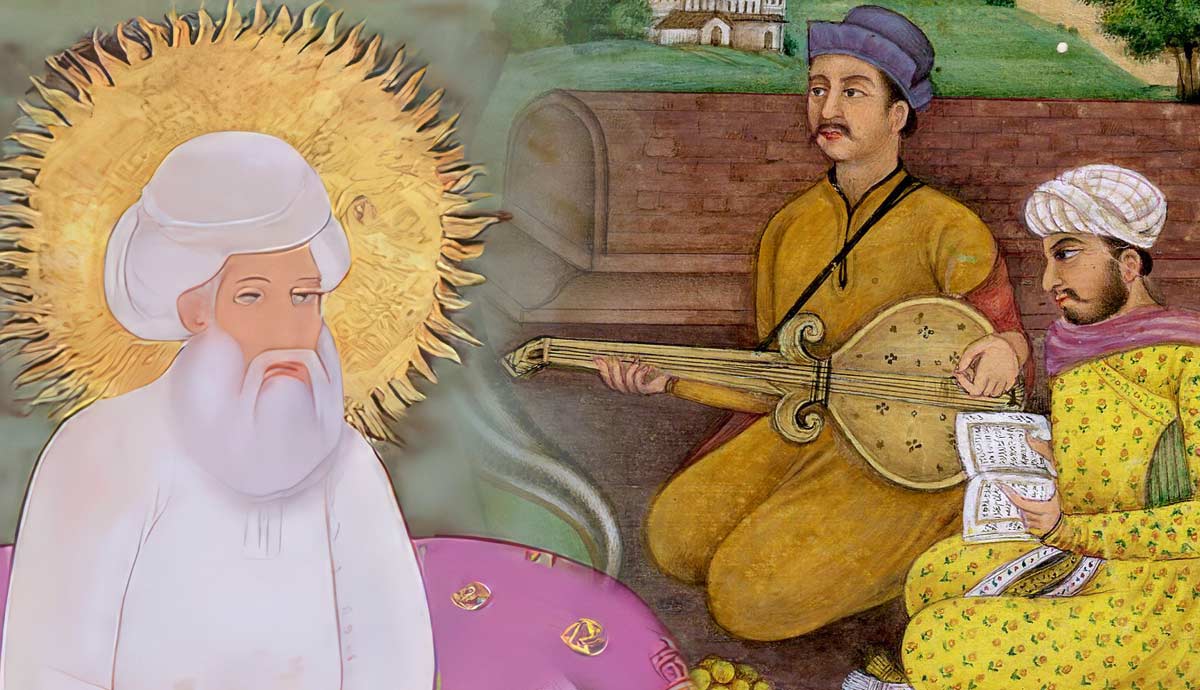

3. The Chishtiyya and Indian Sufism

The Qadriyya and the Naqshbandi orders have had a historically strong following in the Indian Sub-continent, but it was the Chishti order that would characterize Indian Sufism. Originally hailing from the central Asian region of Sistan, now modern-day Iran, the founding sage, Moinuddin Chishti (d. 1236), spent twenty years traveling with his shaykh, Khwaja Uthman Haruni.

The two met with several prominent figures of the time, including Shaykh Abd al-Qadir Jilani. In one often recounted story, Shaykh Abd al-Qadir was moved to declare in a moment of spiritual intensity, “My foot is on the neck of every saint!” And a thousand miles away in India, Mo’in ad-Din Chishti heard this declaration and lowered his head in respect, after which he heard Shaykh Abd al-Qadir tell him, “Go, India is yours.”

Other narrations indicate that Moinuddin Chishti was told by the Prophet Muhammad in a dream to begin teaching in India. Whatever the case may be, it is clear that no figure was as definitive as Moinuddin Chishti bringing Sufism to the Indian Subcontinent.

The Chishti order had several defining features, the most notable being its emphasis and embracing of sama, or “listening,” in which poetry and musical instruments were used to excite the hearts of devotees.

Generally, Muslim scholars would consider music to be unlawful (haram), and associated with worldly frivolity and sensuality. But the Chishtis taught that music simply amplified what was in the hearts of its listeners, whether that be purity or impurity. And so sama was not merely an occasion for entertainment but a sanctified practice appropriate only for those who approached it with the proper intention. Indian culture is historically musical, and so the Chishtis’ inclusion of music, along with their generally tolerant and non-judgmental attitude toward Hindus and other Indian religions, rendered them immensely popular with the common people.

Today, the genre of music known as Qawwali finds its roots in these sama sessions, particularly those of the Chishti sage, Nizam ad-Din Auliya (d. 1325), whose close disciple Amir Khusrow (d. 1325) is considered the founder of the genre.

The popularity and influence of the shaykh’s descendants, notably Baba Farid Ganj-e Shakkar (d. 1265) and his disciple Nizam ad-Din Auliya, often excelled that of both the Islamic scholars (ulema) and the political rulers. Though they had no qualms with Islamic law nor interest in political matters, the Chishtis unabashedly ignored the ulema’s criticism of their practices and refused to even receive visits from the sultans or their viziers. Once when the sultan “name” expressed interest in visiting Nizam ad-Din Auliya, he sent a message back saying, “Just as my zawiya has a front door, so too does it have a back door,” implying that he himself would leave if the ruler were to visit.

The Chishtis’ concerns were not with people of prestige, but with feeding, clothing, and guiding the common people. So was Moinuddin Chishti given the honorific, Khwaja Gharib Nawaz: “The Master who Cherishes the Strangers.” The Shaykh’s tomb (mazar) in Ajmer, India is known as one of, if not the, most visited pilgrimage sites in the world, regularly receiving millions of Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs during the annual three-day celebration of his life.

4. The Mevlevis and the Whirling Dervishes

Perhaps no Sufi group has captured the Western imagination like the Mevlevis and their intricate form of dhikr enacted by the “Whirling Dervishes.” Apart from the Western fascination with them throughout the Ottoman Empire’s reign, even today their eponymous founder, Mawlana (Mevlana) Jalal al-Din Rumi (d. 1273), is purported to be the most widely read poet in the United States. In both the Western and Islamic worlds, Rumi is perhaps the most well-known and revered founder of a Sufi order.

Rumi traveled with his father, Baha al-Din Valad (d. 1232), from his home of Balkh to flee the encroaching Mongol invasions. A Sufi master in his own right, Baha al-Din found favor with the Seljuks in Konya in present-day Turkiye, where Rumi spent the next few decades of his life studying and teaching as a religious and spiritual leader. Yet his journey truly began when he met his teacher, Shams al-Tabriz (d. 1248), a master as knowledgeable as he was fearless and incisive in his quest for Truth.

People often found him both impressive and intolerable, as he was audacious and confrontational in his dealings with people. But in Rumi, Shams found the student he had always been looking for. As for Rumi, he had found his teacher and became ecstatic, disgruntling many of his long-time students who could not understand his change in temperament. It is even said that some of these former students were responsible for Shams’s sudden disappearance.

In his later years, Rumi composed the Masnavi, a massive work of didactic poetry and stories detailing many facets of the Sufi path. Rumi’s joy in divine love was such that he would often begin spinning in circles, chanting God’s names. He did not make this a practice for his students, nor did he formalize it in any way; instead, his son and eventual successor, Sultan Valad (d. 1312), instituted the practice, being a highly reverent and intricate ritual imbued with spiritual and cosmological symbolism. These sessions of dhikr involved Qur’anic recitations, recitals of Rumi’s own poetry, and the famed whirling against the backdrop of a musical ensemble, giving the Mevlevis a distinctly Turkish and Persian flavor.

In his time, Rumi concentrated on his students, who had dwindled to a small core group of sincere and fully committed followers, although he remained highly renowned and respected among the common people and elite alike.

Historically, the Mevlevis were incredibly influential in the Ottoman Empire, alongside the Naqshbandis and other orders such as the Khalwatis (Halvetis) and Bektashis. The respective leaders of these orders held something of a socio-political position among the people, resulting in both respectful and tenuous relations with the ruling classes. Mevlevi zawiyas, or tekkes, were pseudo-monastic, with aspirants undergoing a strict and arduous initiation process and years of complete immersion. These tekkes became a source of social and even economic security for towns distant from the capital in Istanbul, and so often garnered more respect than government officials themselves.

With the establishment of the Republic of Turkiye and its embrace of Western secularism, the Mevlevis and other Sufi orders were officially banned and prohibited from their traditional institutions, though they would continue to meet and practice in private settings.

5. The Shadhili and the Akbarian Tradition

Shifting toward the western Islamic world in North Africa (also known as al-Maghreb), we find the Shadhili order suffusing the spiritual life of Islam. The Shadhili order’s roots also lie with the Qadriyya. The famed Andalusian mystic, Abu Madyan (d. 1198), laid the foundation for the order and completed his own training underShaykhh Abd al-Qadir Jilani. Abu Madyan would go on to be the foremost spiritual guide of the Western Islamic world of his time. His disciple Abd al-Salam ibn Mashish (d. 1228) would himself focus solely on training the order’s eponymous saint, Abu al-Hasan al-Shadhili (d. 1258).

Al-Shadhili’s successor, Abu al-Abbas al Mursi (d. 1287), began to coalesce the Shadhili order, while Mursi’s disciple, Ibn ‘Ata Allah al-Iskandari (d. 1309), systematized the order and became not only its most representative sage but one of the most influential writers in all of Sufism. His work of aphorisms, the Kitab al-Hikmat, would go on to be recited and memorized by spiritual aspirants across the Islamic world up until the present day.

These pithy gems of wisdom reflected the spirit of the Shadhili Order itself. Rather than incorporating intricate musical pieces, Shadhili dhikr gatherings are more raw and visceral, involving hours-long, drum-driven chanting, ebbing, and flowing in intensity.

The Shadhili order also has deep historical ties with the oldest Islamic university, al-Azhar in Cairo, Egypt. Ibn ‘Ata Allah himself was the head of the school at the height of his own spiritual and scholarly prominence. With this firm footing in Islamic orthodoxy, Ibn ‘Ata Allah garnered widespread respect for Sufism, and he also led an outspoken movement in protest against the influential scholar, Ibn Taymiyya, whose puritanical approach to Islam was often at odds with Sufi orders.

However, the order’s most famous figure, and the center of Ibn Taymiyya’s criticism, is undoubtedly the thinker, Muhyi al-din Ibn al-Arabi (d. 1240). Ibn al-Arabi considered himself the disciple of Abu Madyan, although the two never met in person. While al-Shadhili sowed the seeds for what became the most popular Sufi order in the Maghreb, Ibn al-Arabi and his writings spread the complex and mystical philosophical Akbarian tradition to every corner of the Islamic world.

As a final note, these are only five of the most prominent and foundational Sufi Orders. Other prominent orders deserving mention include Khalwatis, an earlier order with large followings in Asia Minor, the Levant, and North Africa. The Khalwatis and Qadriyya influenced the Tijaniyya and Muridiyya orders, which comprise tens of millions of Muslims in West and Central Africa. The Suhrawardi Order was also notable, particularly in the Indian Sub-continent, where it was often in friendly competition with the Chishti Order. Despite the ever-fluctuating tide of history and civilizations, Sufi orders formed and persisted throughout the centuries, always finding new ways to facilitate, and sometimes repackage, traditional Islam to suit contemporary and contextual needs.