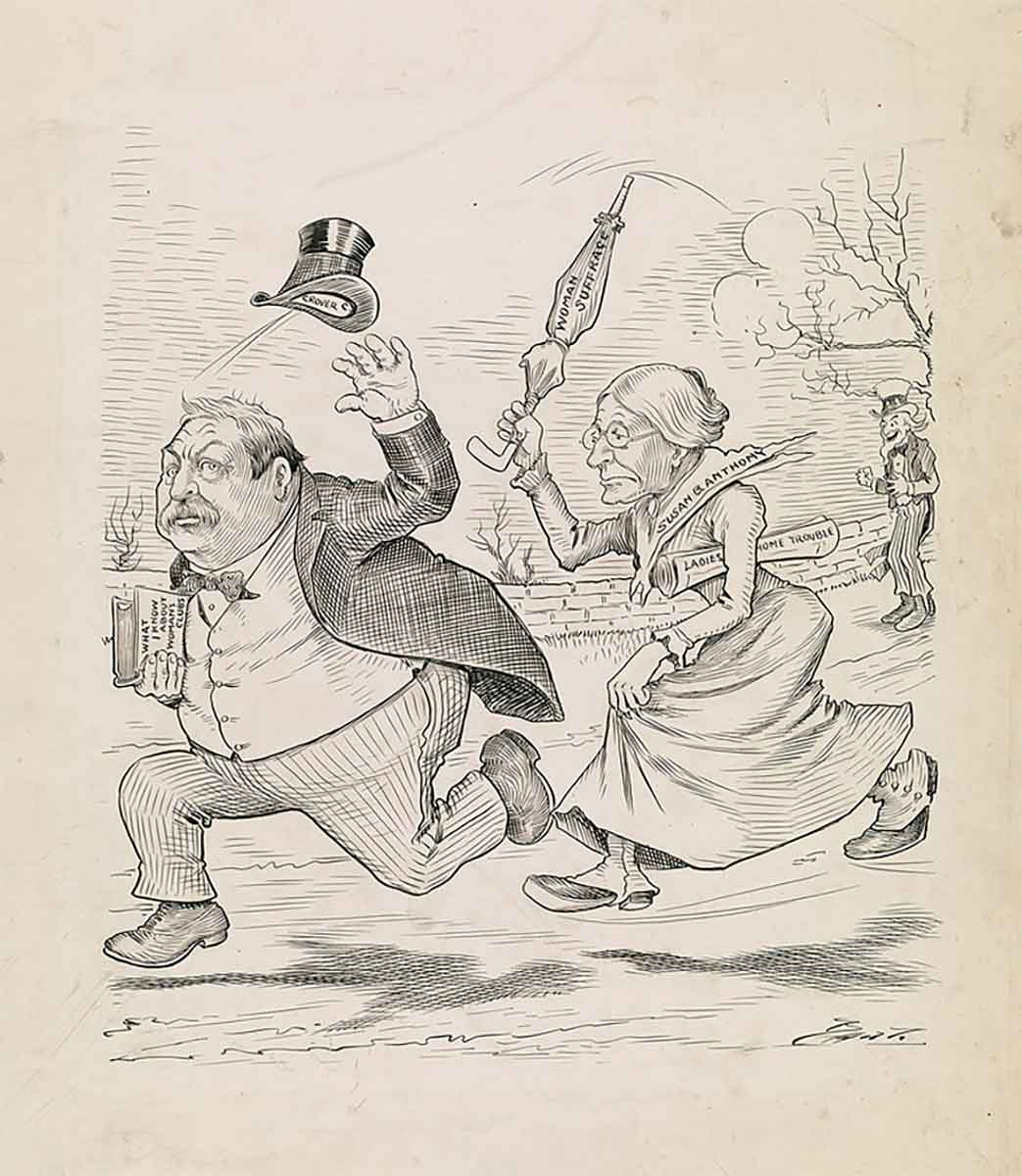

Susan B. Anthony is beloved for her indefatigable efforts on behalf of women’s rights in the 19th century. She gave hundreds of speeches, penned innumerable letters, and sat for interviews with journalists. The result, thankfully, is ongoing access to both her public and private thoughts, even today. Though they speak to a different time, they still offer valuable guidance on how to maintain courage in the face of adversity, argue for what is right and just, and define one’s self while supporting one’s community.

1. Return to the “Old Union” Speech, 1863

“There is great fear expressed on all sides lest this war shall be made a war for the negro. I am willing that it shall be. It is a war to found an empire on the negro in slavery, and shame on us if we do not make it a war to establish the negro in freedom—against whom the whole nation, North and South, East and West, in one mighty conspiracy, has combined from the beginning.”

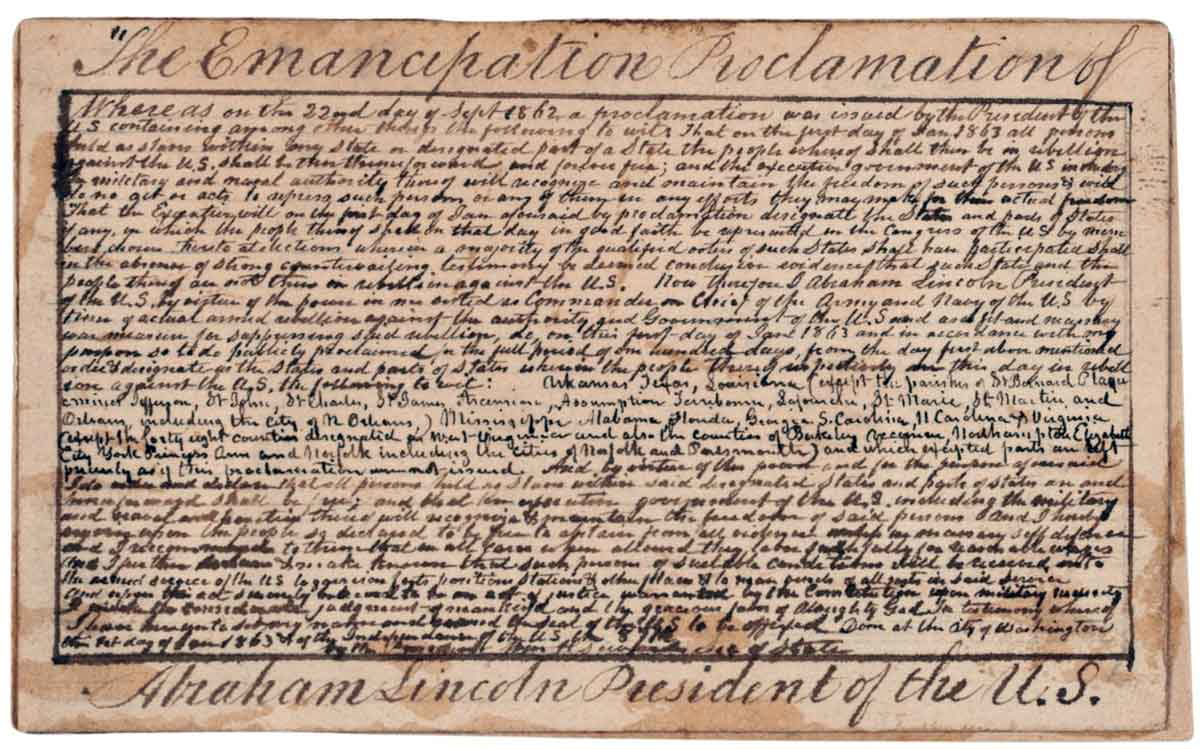

In 1863, the Civil War was two years old and did not appear to be ending any time soon. President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1st of that year, articulating that the war would be about more than just preserving the Union—it was to be about, once and for all, eradicating the system of slavery that had been in place for two hundred years. The Proclamation declared that slaves in states in rebellion (i.e., the Confederacy, not the Border states) “all, and henceforth shall be free.”

While this wasn’t the official end of all slavery throughout the country (which would come in 1865 with the passage of the 13th Amendment), it was of profound importance. The National Archives explains, “it captured the hearts and imagination of millions of Americans and fundamentally transformed the character of the war. After January 1, 1863, every advance of federal troops expanded the domain of freedom. Moreover, the Proclamation announced the acceptance of black men into the Union Army and Navy, enabling the liberated to become liberators. By the end of the war, almost 200,000 black soldiers and sailors had fought for the Union and freedom.”

Susan B. Anthony was absolutely in favor of the Proclamation, and the quote above expresses her opinion forcefully. She understood the importance of the preservation of the Union, but slavery was an evil that she and her family and friends had been fighting against for decades. Her Quaker upbringing stressed equality of all people in the eyes of God, which certainly informed her views on women and men but also on Black people and white people.

2. “Is it a Crime to Vote?” 1872-1873

“The only question left to be settled, now, is: Are women persons? And I hardly believe any of our opponents will have the hardihood to say they are not. Being persons, then, women are citizens, and no state has a right to make any new law, or to enforce any old law, that shall abridge their privileges or immunities. Hence, every discrimination against women in the constitutions and laws of the several states, is to-day null and void, precisely as is every one against negroes.”

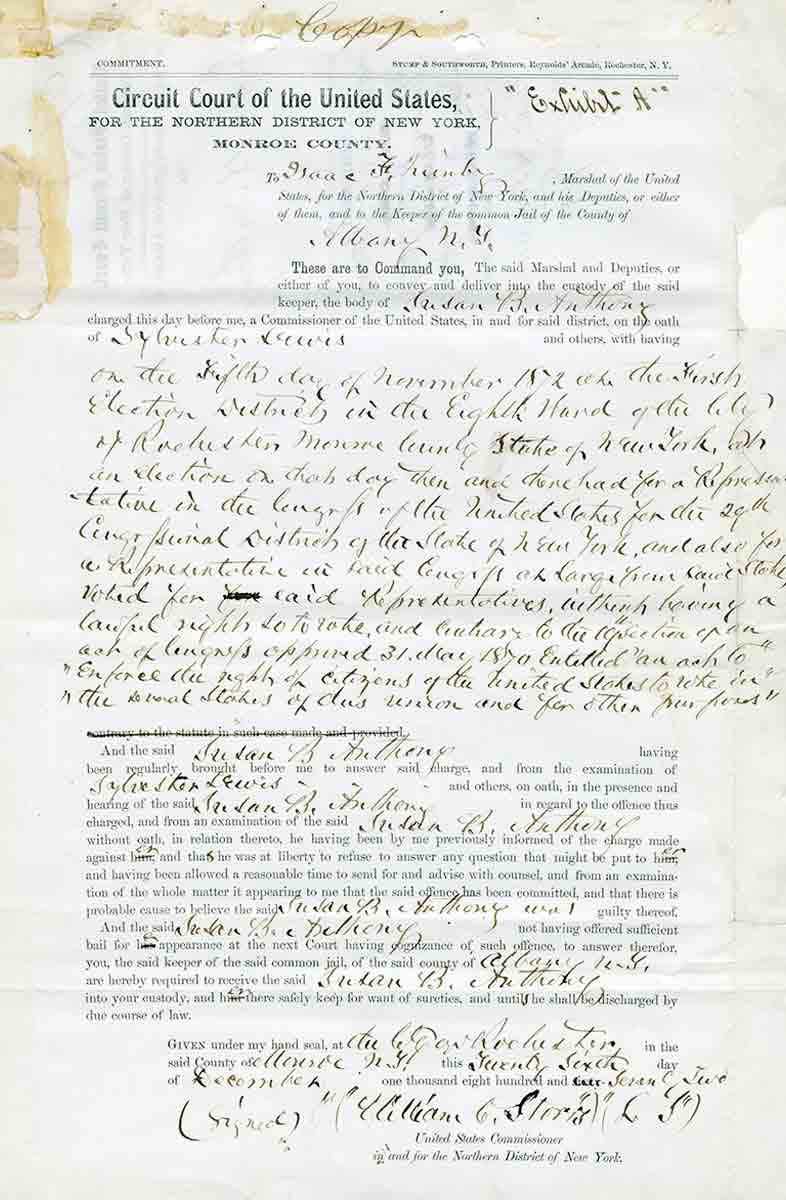

Anthony and about a dozen other women decided to cast a ballot in the 1872 presidential election. The registrar, confused by their presence and demands, allowed them to cast the votes, but Anthony was later arrested at her own home and indicted. She had a trial, but it lacked due process; the judge had instructed the jury to render a guilty verdict regardless of what Anthony said and because Anthony was not allowed to testify for herself. She was found guilty and fined, though she did not pay.

Anthony gave this speech when she was arrested and indicted but had not yet gone to trial. She proclaimed that she would “prove to you that in thus voting, I not only committed no crime, but, instead, simply exercised my citizen’s right, guaranteed to me and all United States citizens by the National Constitution, beyond the power of any State to deny.” Indeed, Anthony gained even more fame from her trial. It did not result in any tangible changes like the right to vote, but it did force the American public and government to grapple with the big questions she posed.

3. Social Purity, 1875

“Women, like men, must not only have “fair play” in the world of work and self-support, but, like men, must be eligible to all the honors and emoluments of society and government. Marriage, to women as to men, must be a luxury, not a necessity; an incident of life, not all of it. And the only possible way to accomplish this great change is to accord to women equal power in the making, shaping and controlling of the circumstances of life. That equality of rights and privileges is vested in the ballot, the symbol of power in a republic. Hence, our first and most urgent demand—that women shall be protected in the exercise of their inherent, personal, citizen’s right to a voice in the government, municipal, state, national.”

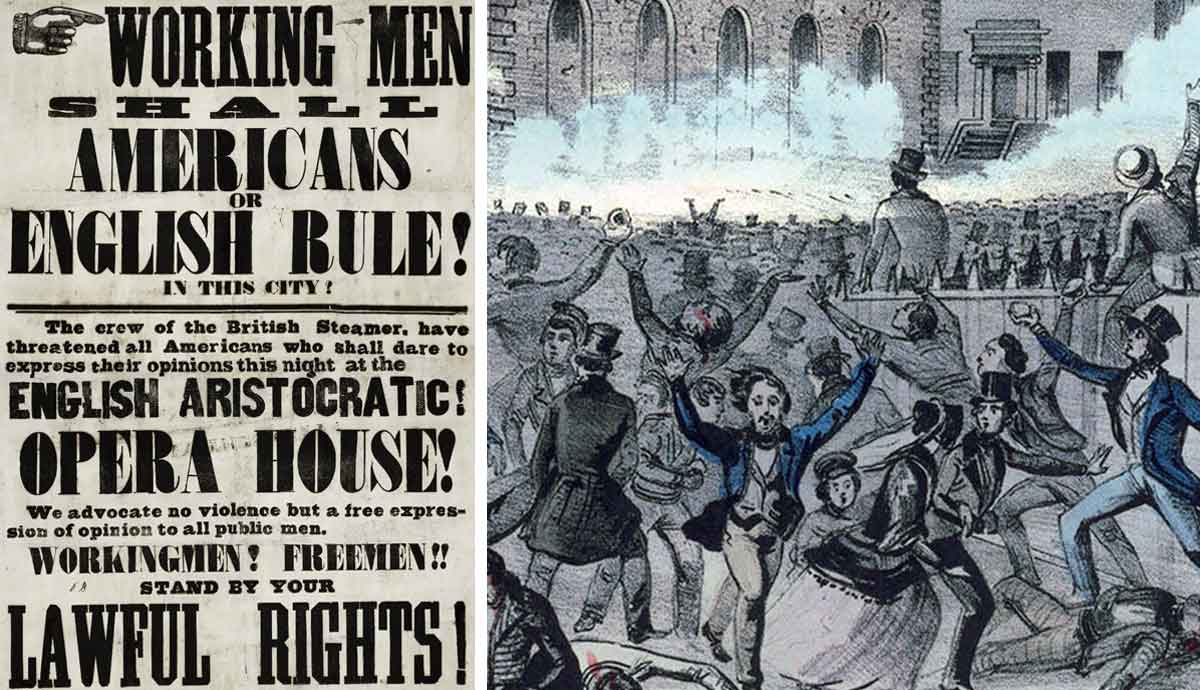

Anthony delivered this speech for the first time at the Grand Opera House in Chicago, Illinois, for a Sunday afternoon lecture course. Her fame had enticed a massive crowd, and she could not get inside the House, instead having to go a back way to reach the stage.

In this speech, she asserted that women need to have as much a say as men do in creating and enforcing the conditions that govern their lives. They need to have political power so they can then have power in other areas, such as marriage. Marriage was the most intimate and important relationship in a woman’s life and one that could, and often did, lead to oppression and misery.

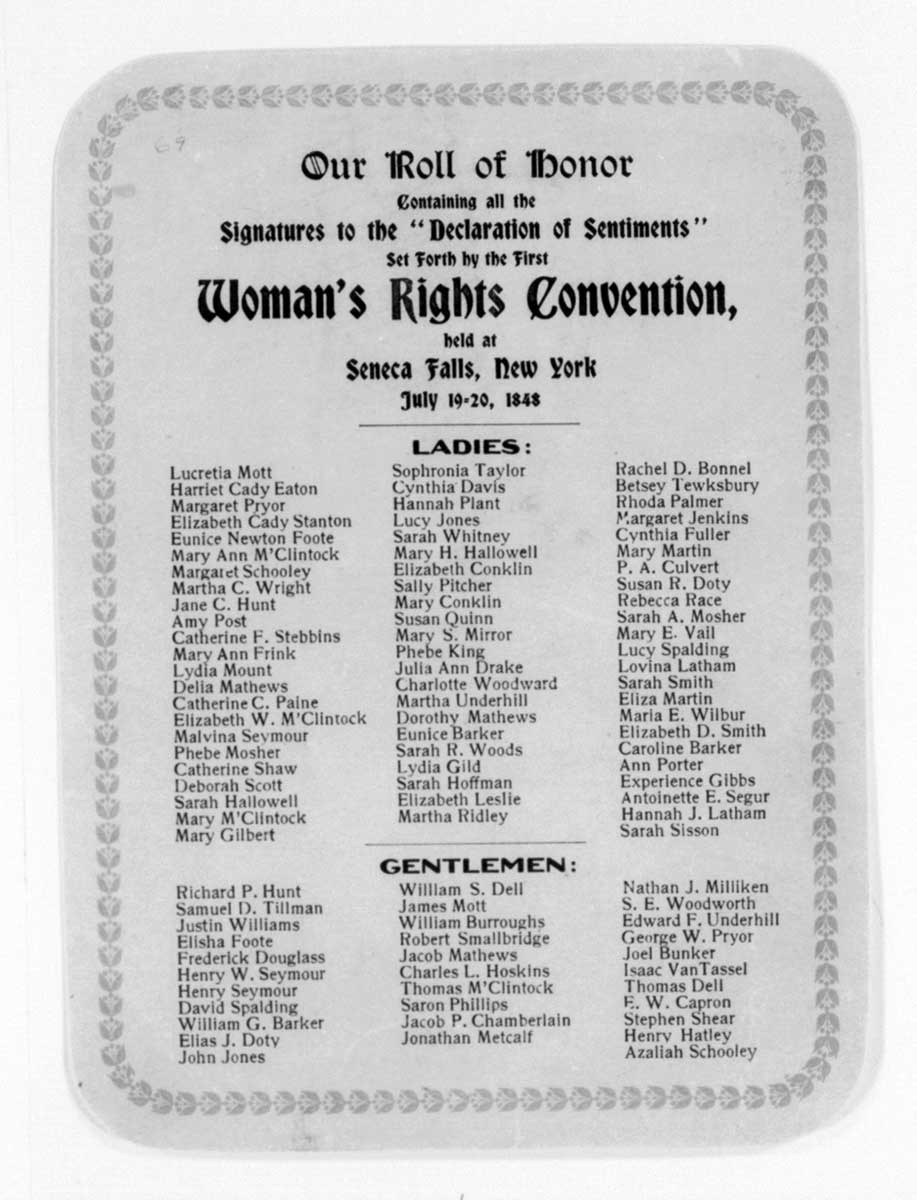

The Declaration of Sentiments, which was devised by the attendees of the 1848 Women’s Rights Convention at Seneca Falls, New York, was drawn up in the style of the Declaration of Independence and listed the ways in which men had deprived women of their natural rights. Marriage was mentioned several times, most dramatically in this claim: “In the covenant of marriage, she is compelled to promise obedience to her husband, he becoming, to all intents and purposes, her master—the law giving him power to deprive her of her liberty, and to administer chastisement.” Anthony’s comments on marriage in her speech were a reflection of just how much this issue mattered to women, and how expanding women’s political freedom would help expand women’s marital freedom.

4. Declaration of Rights of the Women of the United States, July 4, 1876

“Our faith is firm and unwavering in the broad principles of human rights proclaimed in 1776, not only as abstract truths, but as the corner stones of a republic. Yet we cannot forget, even in this glad hour, that while all men of every race, and clime, and condition, have been invested with the full rights of citizenship under our hospitable flag, all women still suffer the degradation of disfranchisement.”

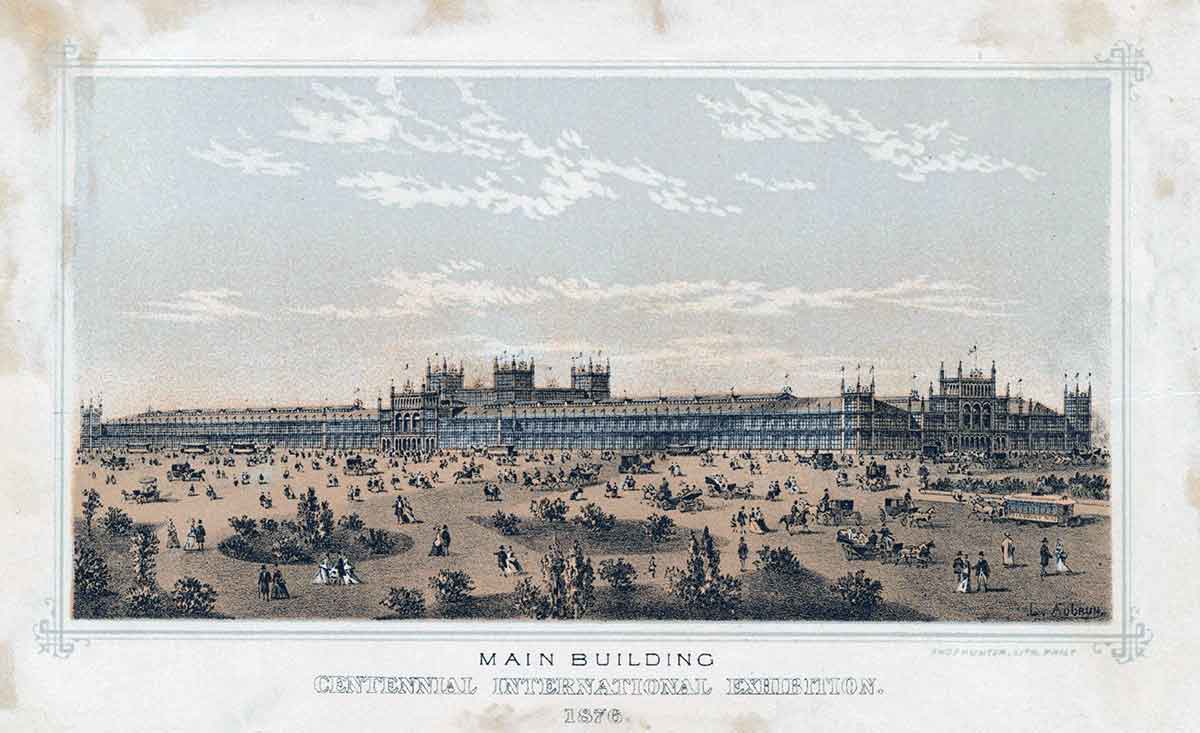

The nation’s centennial was celebrated in 1876 with parades, fireworks, speeches, and a massive exhibition known as the 1876 Centennial Exhibition, or the first World’s Fair. Held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, it was meant to showcase the United States’ industrial accomplishments and celebrate its enduring democracy.

Five women from the National Woman Suffrage Association, which included Anthony, were given passes to attend the Independence Day ceremony but were not allowed to present a declaration they’d written. However, when Senator Richard Henry Lee finished reading his notes, the women moved in front of him to the platform, and Anthony read their declaration. They also passed out copies to the people in attendance.

The quote above shows how the women connected what they were demanding in terms of the privileges of citizenship to what the Americans had demanded from Great Britain when they declared their independence in 1776. They are not asking for anything other than basic human rights and the basic rights given to people in a democratic country. By framing it as such, Anthony and her compatriots offered a logical argument rather than one rooted in caprice, temporality, or passion.

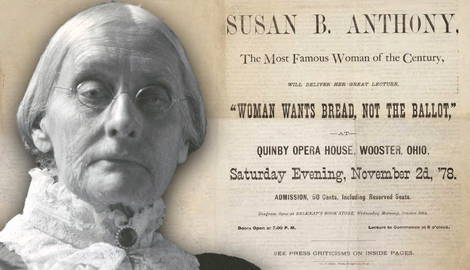

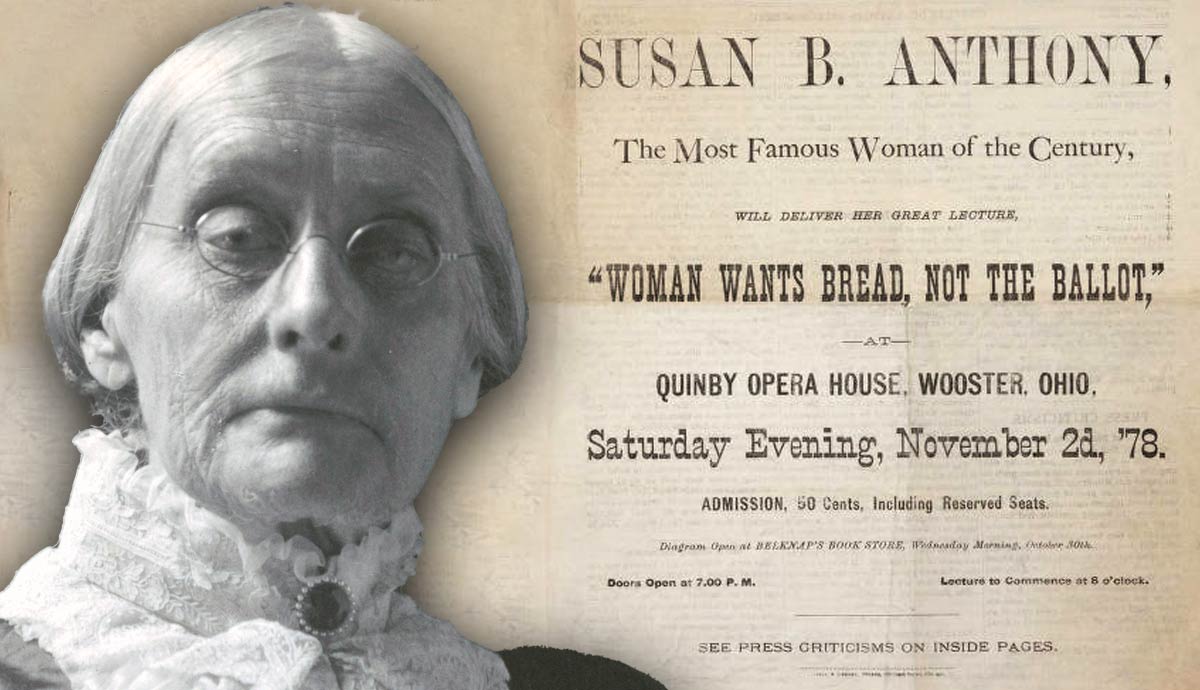

5. “Woman Wants Bread, Not the Ballot!”

“Governments cannot afford to ignore the rights of those holding the ballot, who make and unmake every law and law-maker. It is not because the members of Congress are tyrants that women receive only half pay and are admitted only to inferior positions in the departments. It is simply in obedience to a law of political economy, which makes it impossible for a government to do as much for the disenfranchised as for the enfranchised. Women are no exception to the general rule. As disfranchisement always has degraded men, socially, morally and industrially, so today it is disfranchisement that degrades women in the same spheres.”

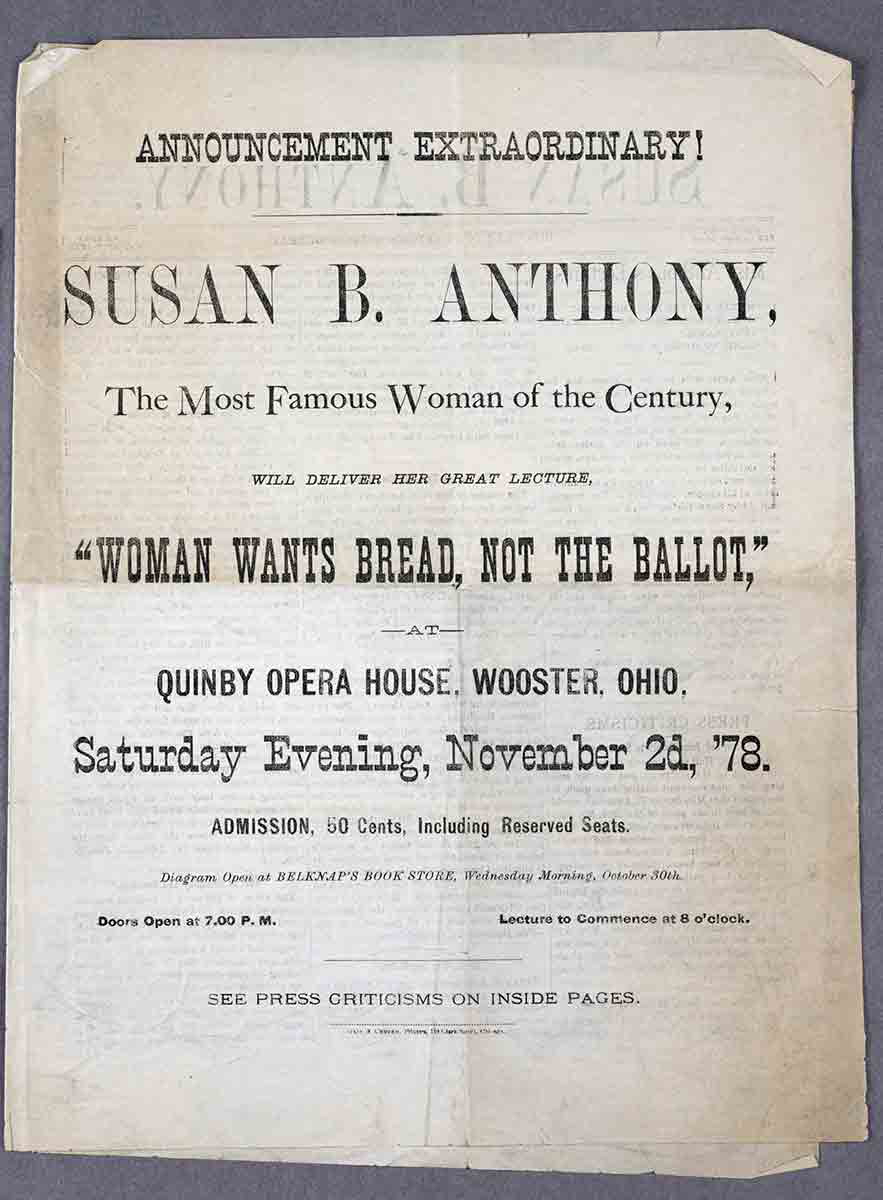

Anthony was a schoolteacher for many years and eventually realized that women in her profession were paid far less than men. In her conversations with other women, she noted that this discrepancy was not just confined to teaching and was, in fact, widespread. In her role in the temperance movement, she also saw that she was treated differently because she was a woman. All of this led her to conclude that attaining the vote was the key to unlocking changes in all these other areas of life.

In this speech, which she delivered multiple times throughout the 1880s, she conceded that the government had no need to seriously consider the plight of those who did not have the full privileges of citizenship. It would only be when women attained that privilege that they would have the power to contest the egregious inequalities they faced in American life.

At the end of the speech, she reminded (or arguably warned) her listeners that women had been “driven to violations of law and order” in some cases (“Women’s crusades against saloons, brothels and gambling-dens”) and that they needed to be taken seriously in their demands. This is reminiscent of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s 1963 “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” in which he said that “the Negro has many pent up resentments and latent frustrations, and he must release them…If his repressed emotions are not released in nonviolent ways, they will seek expression through violence; this is not a threat but a fact of history.”

6. Statement Before the US House Committee on the Judiciary, Jan. 24, 1880

“Then look at the boys of this generation. Before the boy’s head reaches the level of the table, he learns that he is one of the superior class and that when he is twenty-one years old he will make laws for Mrs. Saxon, Mrs. Gage, and all these ladies who are mothers. His mother teaches him all the requisites for success in after life. She says: ‘My son, you must not chew, nor smoke, nor gamble, nor swear, nor be a libertine; you must be a good man.’ The boy looks his mother in the face, unbelievingly, and, perchance, at his father, who is guilty of every one of the vices which the mother says he must avoid if he would become a great man.”

The Senate Select Committee on Women’s Suffrage convened in 1880. Anthony and other delegates to the 12th Washington convention of NWSA were allowed to present their statements. Anthony’s statement had several components to it, and at one point, she told a story that resulted in the (all male) members of the committee laughing. One member apologized to her and said their laughter did not mean they were not taking the women seriously, and Anthony replied, “You are not laughing at me; you are treating me respectfully, because you are hearing my argument; you are not asleep, not one of you, and I am delighted.”

This selection offers an interesting argument. It uses a young boy as its main “character,” explaining how he will learn before he is even tall enough to reach the tabletop that he is superior to all the women in his life and will be able to make laws that govern all aspects of their lives. He is incredulous when he hears from his mother about how he must behave and what vices to avoid, as his own father indulges in those vices all the time. By using children, mothers, and fathers as figures in her argument about why it is wrong to deny women the franchise, she appeals to the traditional, family-oriented senators before her. She explains how the current system is not just bad for adults but for children and how it is deeply hypocritical.

7. Organization Among Women as an Instrument in Promoting the Interests of Political Liberty, May 20, 1893

“We have known how to make the noise, you see, and how to bring the whole world to our organization in spirit, if not in person. I would philosophize on the reason why. It is because women have been taught always to work for something else than their own personal freedom; and the hardest thing in the world is to organize women for the one purpose of securing their political liberty and political equality.”

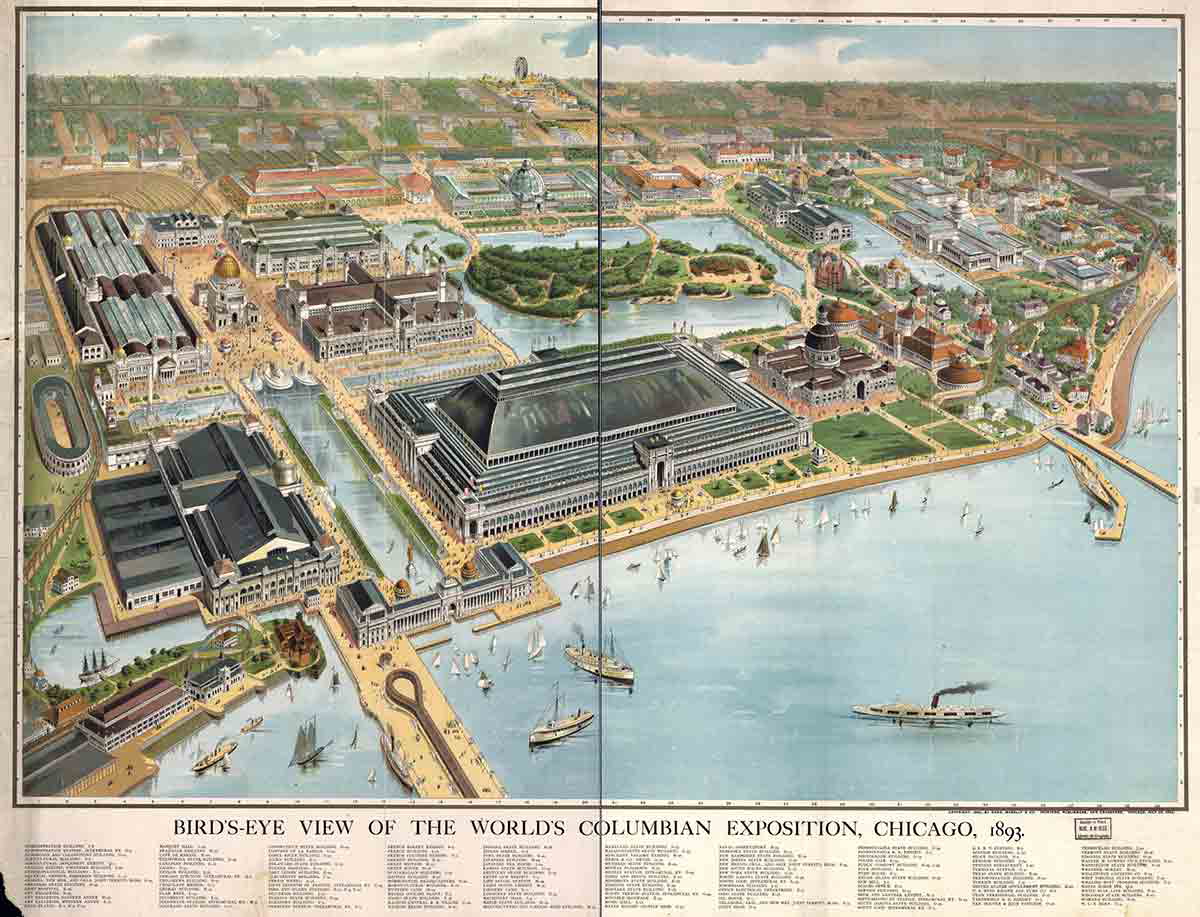

Anthony delivered this speech for the World’s Congress of Representative Women at the Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893. This Exposition, or the 1893 World’s Fair, celebrated Columbus’s arrival in the Americas 401 years prior and was intended to showcase America’s industrial might, cultural contributions, and moral virtues. The Court of Honor was comprised of exhibition spaces for the new inventions and appliances of the era, and the fact that all of this was illuminated by Thomas Edison’s light bulbs was nothing short of astonishing.

The Midway was a mile-long commercial strip that provided concessions (hamburgers and soda for the first time!) and exhilarating entertainment. There was the world’s first Ferris wheel; performances by Harry Houdini, Scott Joplin, and Buffalo Bill Cody and his Wild West Show; and “exotic” displays of other cultures. And there were talks: talks about the closing of the American frontier, socialism, politics, the law, and women’s suffrage.

Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were two of the speakers on the subject of suffrage. In this quote, Anthony accounts for why it is so difficult for women to organize for something that is so obviously in their best interest. She explains that the condition of women is to constantly put themselves last, to prioritize their husbands and children and elders, and to sublimate their own needs and desires. Why, then, would they find it easy or natural to come together with a list of demands?

8. Statement Before the US House Committee on the Judiciary, Jan. 28, 1896

The Chairman. “But, Miss Anthony, what I want to know is, where do you stand with the women? We are given to understand that as a rule women do not want the suffrage.”

Miss Anthony. “I do not care where we stand with the women! We have been getting them for fifty years. We are after the men now. Men have the vote, and it is all nonsense to refer me back to the women.”

Anthony delivered a statement in front of the Senate and the House of Representatives asking for an amendment to the Constitution that would give women the right to vote. She explained that it was phrased just like the 15th Amendment—“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex”—and was necessary to discuss and vote on in order to “know how far along in the progress of civilization we have moved; just where we stand.”

The Chairman asked her about women, noting that they did not seem to want suffrage, and she replied that she did not care so much about women as men, because men were the ones who had the power to actually bestow the right to vote. When the Chairman pressed that point, she scoffed that children did not want to be in school but that they had to be because it was best for them and that women were classed like children, so her strategy to go to the men made sense. Undeterred by any of the Chairman’s questions, she concluded by acknowledging that she’d “been persecuting you and your predecessors all these years with my presence” and that if they were “the same men [they] would be tired of me.” Her tenacity and pragmatism were still very much in effect, even though she’d been arguing for the same thing for over thirty years by this point.

9. “Our Only Hope,” 1896 Interview With Nellie Bly in The World

“I had barked up the temperance tree, and I’d barked up the teachers’ tree and I couldn’t do anything. I had learned where our only hope rested. I got petitions signed for property laws and for suffrage.”

Nellie Bly was one of the most famous journalists of her era, a fame she attained by going undercover as a patient at Blackwell’s Island, the notorious mental health asylum in New York City, in 1887. She wrote about the terrible conditions she discovered in the New York World, and her exposé helped usher in various reforms. She went on to write about political corruption, working conditions, and child welfare.

Bly interviewed many prominent individuals throughout her career, including Emma Goldman and Eugene V. Debs. Her interview with Anthony took place in 1896, days before Anthony’s 76th birthday and not long after Anthony spoke to Congress about a proposed amendment to the Constitution enshrining women’s suffrage. In an article entitled “Champion of Her Sex,” Bly asked about Anthony’s upbringing and her views on all manner of women’s issues, including divorce and suffrage. In this quote, Anthony succinctly and colorfully explains why she finally realized suffrage was the most important thing to pursue, as it would unlock remedies for all of the other social inequalities that plagued women.

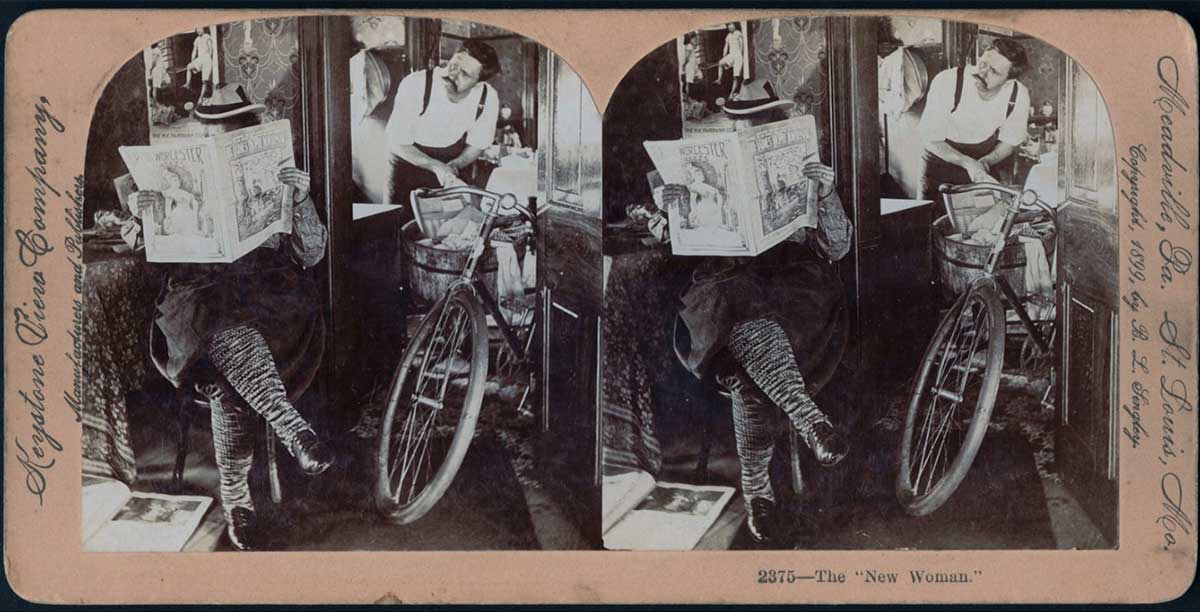

10. “The New Woman,” 1896 Interview With Nellie Bly in The World

“What do you think the new woman will be?”

“She’ll be free,” said Miss Anthony. “Then she’ll be whatever her best judgment wants to be. We can no more imagine what the true woman will be than we can what the true man will be. We haven’t had him yet. And we won’t until all women are free and equal.”

Midway through the article, Bly asks Anthony about the “new woman.” This “new woman,” as described by the Oxford Research Encyclopedia, was a “real, flesh-and-blood women, and also to an abstract idea or a visual archetype” who “represented a generation of women who came of age between 1890 and 1920 and challenged gender norms and structures by asserting a new public presence through work, education, entertainment, and politics, while also denoting a distinctly modern appearance that contrasted with Victorian ideals.” It was a term people were very familiar with, and by bringing it up, an effective way to solicit one’s opinion about “women’s issues.”

Anthony’s answer is a testament to her intelligence, insightfulness, and ability to inspire hope in others. She stresses freedom, naturally, but frames it in a way that goes beyond the right to vote. A woman will have the opportunity to define the contours of her own life and to be who she wants to be. In fact, it’s not right for Anthony herself to define what the new woman will be or look like because it’s for those women themselves to decide.