Also called small wars, these expeditions influenced the development of Marine Corps tactics and counterinsurgency strategies for future conflicts. Despite the name, these actions were not officially undertaken with bananas in mind but under the pretense of restoring stability. Evidence suggests these invasions and occupations were motivated by protecting American businesses, exerting financial and military control in the region, and keeping European influence away from the continent.

Justifications for the Banana Wars

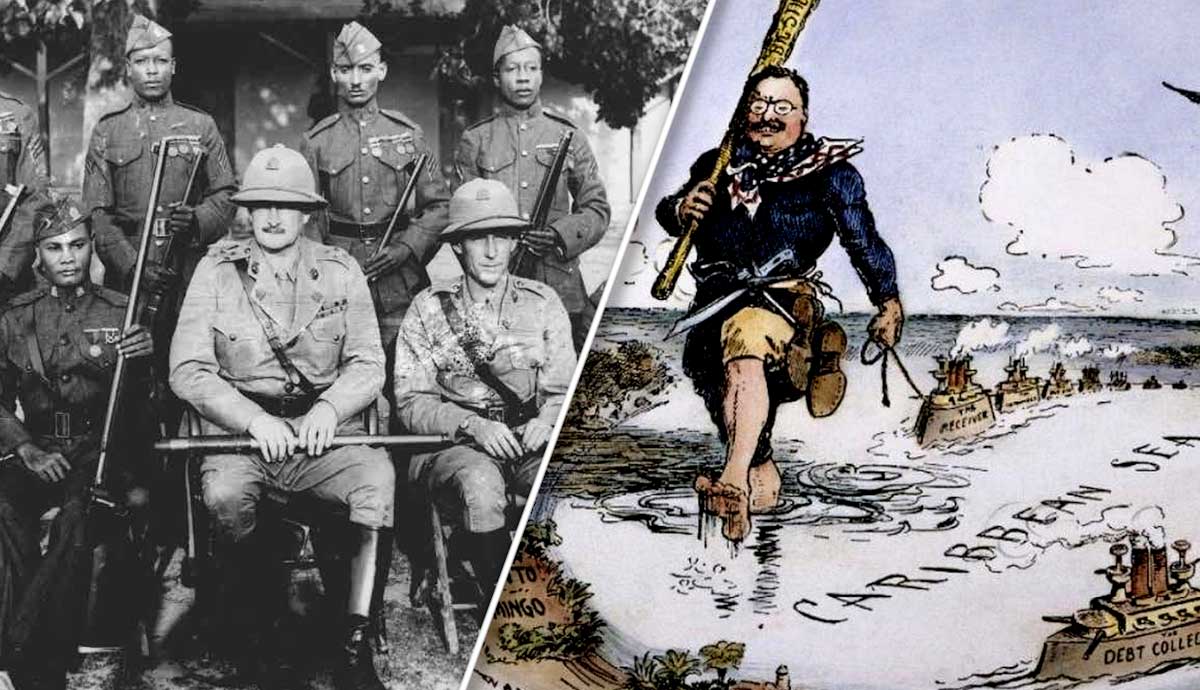

James Monroe first outlined a principle for US dominance of the region in the 1823 Monroe Doctrine. He implored European countries not to further colonize the Western Hemisphere and to respect it as America’s region of influence. In 1904, European powers threatened war against Central American nations such as Venezuela to collect debts. President Theodore Roosevelt then proclaimed the Roosevelt Corollary to the existing Monroe Doctrine. He stated the United States could use military force to compel countries in the Americas to pay their debts. This was to avoid provoking European intervention and thus endangering the security of other nations.

The corollary had little effect on relations with Europe but was the impetus for wars against neighbors in the Western Hemisphere. The Roosevelt Corollary and involvement in the Caribbean was the first time American politicians emphasized regional stability in foreign policy. William Howard Taft echoed this with his philosophy of dollar diplomacy, with interventions staged to protect American commercial interests abroad. Woodrow Wilson directed the occupation of Haiti under the pretext of promoting democracy. This was also where military interventions became commonplace.

The Spanish-American War and its Effects

The United States, with indigenous revolutionary forces, soundly defeated Spain in 1898 in the Spanish-American War. Filipinos issued a Declaration of Independence and nearly defeated Spanish troops before the US arrived. Soon after, President William McKinley dashed the hopes of Filipino combatants by announcing he would annex the Philippines. This action drew resistance from members of Congress and prominent Americans. Despite outcry, the Treaty of Paris officially ended the war with Spain, giving the United States control of the Philippines, Guam, Puerto Rico, and exclusive rights over Cuba.

American service members provoked war in the Philippines to cement control of the island, hoping to expand opportunities for international trade. Two hundred fifty thousand Filipinos were killed, mostly civilians subjected to human rights abuses. Torture, mass executions, and forced relocation were common practices of American soldiers. Though the conflict ended in victory, it became clear that overt large-scale war was an inefficient way to spread American influence. Future operations closer to home were marked by their unjust nature as well.

Smedley Butler Claimed They Were A Racket

Smedley Butler was a Marine Corps officer for thirty-four years and, by the time of his death in 1940, was the most decorated Marine in American history. Butler earned two Medals of Honor in small wars, during combat in Mexico and Haiti, and also fought in the Philippines, China, Central America, and France.

He wrote War is a Racket in 1935, claiming the wars he fought were at the behest of business interests stateside. Butler characterized these interventions as forays to allow the entry of oil, banking, and sugar conglomerates into foreign markets. Official justifications for the wars understandably do not mention these motivations. Historians include various conflicts in the “Banana Wars,” but interventions in Nicaragua, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic are almost universally included.

Two Banana Wars in Nicaragua

President Jose Zelaya of Nicaragua desired to conquer and unify neighboring countries under a single flag, threatening regional peace. Small contingents of American soldiers arrived in Nicaragua in 1894, 1898, and 1899 to protect US property during domestic struggles under Zelaya’s reign. In 1909, the Taft administration seized the chance to covertly support an uprising against Zelaya. Nicaraguan troops executed two Americans serving in the revolutionary forces, giving cause for the Marine Corps to invade and back Juan Estrada as the new president.

Estrada inherited a corrupt government with meager funds. The United States brokered a treaty in which American banks would issue a large loan, collect taxes on foreign trade, and gain controlling interests in the national bank and railway. Political friction persisted as additional revolts occurred in the following years. US Marines remained in the country to protect American property. They left in 1925 after Nicaragua repaid their loans and bought back their bank and railroad.

American Marines deployed to Nicaragua again from 1927 to 1932. In part, the US wished to safeguard a presidential election and train a Nicaraguan National Guard to ensure continued stability. Nicaragua was amid a civil war that endangered US corporations operating within. Mexico supplied the opposition with weapons, and the US did not want to allow their neighbor to compete in Central America. Resistance forces under Augusto Sandino fought against American occupation under suspicions that the troops would tamper with the political process. After two successful elections, US troops fully withdrew.

Occupation and Oppression of Haiti

Haiti accumulated massive debt to European countries by 1914, so much so that France seized their navy, and Britain and Germany both threatened war. Germany entered discussions with Haiti to acquire exclusive trading rights and land for a coal station. Multinational conglomerates established sugar plantations to the detriment of small Haitian planters. A revolt broke out in 1915, and President Woodrow Wilson dispatched troops in response.

Military occupation fostered hierarchies and divisions in Haiti. The US stifled the press, used forced labor, and compelled the adoption of a new constitution that allowed American businesses to own property. Haitians resisted, and in only the first five years, American forces killed 2,250. In 1921, the US Senate investigated claims of human rights violations and, in response, reorganized the occupation government. By 1929, labor strikes and other forms of resistance catalyzed the end of American governance, which was completed in 1934.

Europe, Sugar, & the Dominican Republic

The United States seized control over Dominican customs collection in 1905 under the Roosevelt Corollary to pay the country’s European creditors and avoid European intervention. American sugar companies operating on the island priced out local growers, furthering debt problems. After Dominican president Ramon Caceres was assassinated in 1912, US Marines landed and installed a new president. Juan Isidro Jimenez became head of state in 1916 and accommodated American interests to the displeasure of his constituents. The Marine Corps arrived to support Jimenez and announced occupation that year.

Under the occupation government, sugar corporations operated virtually unchecked. The South Porto Rico Sugar Company burned two villages to clear land for their fields. Ninety-five percent of Dominican sugar was exported to the US, with the local workers seeing practically no benefit from their labor. The military presence was also in place to dissuade Germany from expanding further into the Caribbean.

After World War I, European influence and interest in the Caribbean declined, along with the perceived military necessity of the island. American citizens heard the Great War propaganda calling for the rights of small nations to exist independently. They realized this ideal should apply to the Dominican Republic as well. In June 1920, Dominicans launched “patriotic week,” a time of fundraising to lobby for independence. Later that year, President Wilson began withdrawing the occupation force.

The Wilson administration authorized the withdrawal under the pretext that they reestablished peace and stability. Yet, the Dominican government was in severe debt and proved unable to provide public services in the ensuing economic crisis. Foreign development and extraction of key resources left their development stunted.

Good Neighbor Policy to Domino Theory

Franklin Delano Roosevelt brought a noninterventionist position to the presidency. In his 1933 inaugural address, FDR outlined his good neighbor policy. To Roosevelt, a good neighbor respects the rights of others. Secretary of State Cordell Hull affirmed this belief at the Montevideo Conference that December, declaring, “No state has the right to intervene in the internal or external affairs of another.” The following year, the Roosevelt administration repealed the treaty permitting American dominance over Cuba and voluntarily withdrew from Haiti.

During the Cold War, America returned to imperialist policy as leaders feared that a single country becoming communist could create a domino effect, leading to the conversion of its neighbors. Subsequent interventions are occasionally categorized with the earlier Banana Wars, such as those in the Dominican Republic (1965), Grenada (1983), and Panama (1989). These conflicts were similarly initiated under the auspices of restoring stability while exercising US dominion over the region.

Military Lessons Learned in the Banana Wars

Irregular warfare in these conflicts molded Marine Corps doctrine. Armed occupation showed the importance of local guides and partisans. Service members learned how to defend against guerilla forces and establish enclaves for noncombatants to live safely. Building roads, schools, and medical facilities increased native support.

Lessons from these expeditions were compiled into the Small Wars Manual in 1940. Practices outlined in this book continue to be conducted in struggles against insurgents today. It highlighted the notion that “in small wars, tolerance, sympathy, and kindness should be the keynote to our relationship with the mass of the population.” The Small Wars Manual was the source for a revised counterinsurgency guidebook designed for the War in Afghanistan.

US military and civil involvement in these Central American nations offered larger-scale lessons than combat tactics. The Banana Wars were primitive attempts at nation-building, ostensibly under the guise of affirming democracy. Civic institutions established by American occupiers were often not free and fair, neglecting the needs of citizens in favor of continued US hegemony. During wars in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan, the treatment of civilians and restructuring of government systems drew on experiences from prolonged involvement in the Caribbean and Latin America.

Were the Banana Wars Justified?

Just War Theory identifies factors that justify military conflict with a foreign power. Explanations for initiating and escalating violence have been offered for thousands of years, and in modern times, spokespeople cite common qualifying factors. Wars must have a just cause and intent and be started by a legitimate authority with the ultimate, plausible goal of peace. Armed response must be proportionate and only undertaken as a last resort if all diplomatic options fail. The last resort doctrine is esteemed, with war viewed as an unmatched horror that should only be pursued after expending every potential nonmilitary resolution.

However, these actions violated every component of the Just War Theory. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the United States used military intervention as the first and primary option against Caribbean and Central American countries. The causes and intentions for these expeditions were chiefly to exert control. The US pursued peace to gain and protect that control. The Constitution gives the power to declare war solely to Congress, and they levied no declaration of war against the targeted countries. Violence was disproportionate, with deaths of Salvadorans from US intervention forty times higher, adjusted for the population, than deaths of Americans in Vietnam, for example.

The Banana Wars exhibited the American desire to expand and preserve national interests economically, militarily, or otherwise. With the Monroe Doctrine as justification, the United States perpetrated these wars to maintain power over the Western Hemisphere.