There’s no doubt the Mongols qualify as perhaps history’s great military force. From Korea’s far shore to Poland and Egypt’s borders, their cavalry conquered. Defeats were few and far between as they expanded from 1206 to 1368, building an unmatched empire. Cities upon countries fell to them, occasionally based on terror alone.

Yet for all their might and ferocity, their seaborne operations only enjoyed limited successes. During their campaigns, the Mongols utilized rivers for sieges, support, and crossings. This proved moderately successful, such as in the 1258 sack of Baghdad. Here, they used boats on the Tigris to move siege engines and isolate the city before it fell. But actual oceans became a conundrum.

The Horse Lords Meet the East China Sea

For the Mongol leader and Emperor Kublai Khan, Japan became a thorn, albeit of his own making. In the late 1260s, attempts to cajole or bully Japan into surrender ended with dead envoys and an angry Khan. Despite being a land power with limited experience in river or coastal naval operations, the Mongols invaded.

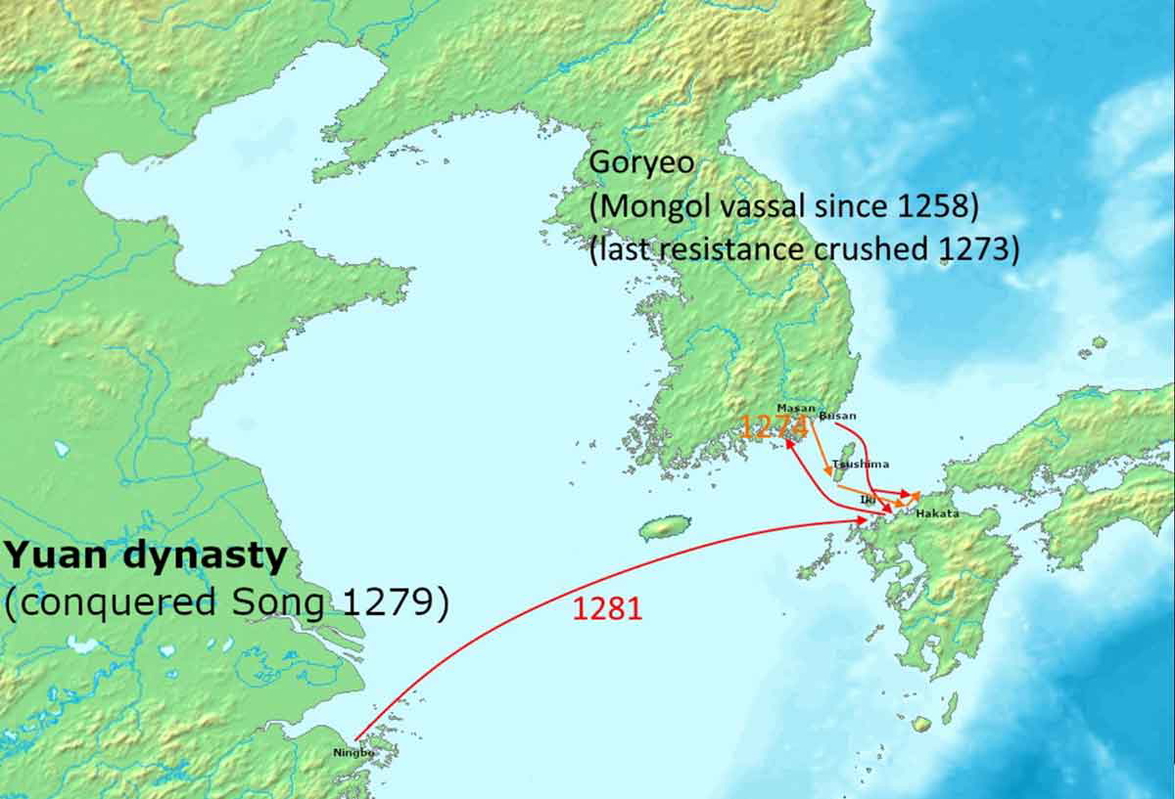

Around October 1274, the Mongols assembled their fleet of Korean and Chinese ships. With 900 ships and 30,000 fighters, their invasion landed at Imperial Japan’s Hakata Bay. Despite initial success, formidable Japanese defenses, and more so, the East China Sea exposed the Mongols’ nautical fragility.

The East China Sea and a Raging Typhoon

First, the Mongols unwittingly created their own mess. The East China Sea, notoriously dangerous and known for storms, wouldn’t be forgiving of any faults. The Mongol ships, built in Korean and Chinese shipyards, proved to be flimsy and unsuited for an ocean journey. Here, the Mongols had no option, being a land-based power.

The Mongol logistics quickly deteriorated with the Hakata Bay landings. Getting supplies to their fleet between China, Korea, and Japan across an open sea was difficult. With no established land bases, the invaders relied on resupply by ship. Japanese raids and ocean storms often disrupted resupply efforts. Communication problems between the three groups only grew worse.

Well-built Japanese defenses, raids, and weather conditions forced the Mongols to concentrate their fleet at specific coastal spots. While this may seem defensive, it would be a mistake. Inevitably, the notoriously unpredictable sea struck in its worst form: a typhoon.

For the Mongols, the typhoon’s fury and sudden onset proved devastating. Their flat-bottomed ships, hastily built, anchored and crowded together in the exposed Hakata Bay, got hammered. Massive waves, severe rain, and wind destroyed about a third of the fleet immediately. Some capsized while others got driven onto rocks. Some 13,000 soldiers are thought to have perished.

Despite this disaster, Kublai Khan remained undaunted, viewing this setback as a threat to Mongol authority. He simply began planning the next larger one. With lessons learned and more time, the Mongols ordered Chinese shipyards to build bigger, blue-water capable ships. The invasion force would be over 140,000 men in two fleets (4,000 plus ships) from Korea and China. Early June was selected to avoid the peak typhoon season.

The second fleet from China left much later than expected. On June 23, 1281, the first fleet struck Japan again at Hakata Bay, against orders to wait.

However, the second fleet slowly traveled to Japan, beset by hostile currents and adverse winds. By August, the fleets combined, and the savage fighting continued. And the East China Sea again played the foil, answering Japan’s imperial prayers.

A second great typhoon struck, wrecking the huge Mongol fleet. An estimated one-half drowned, with any survivors hunted down by Japanese forces. The Mongols wouldn’t return to Japan.

Not Just in the East China Sea

Like the sea named above, the South China Sea also played a part in defying Asia’s horse lords. In 1293, Kublai Khan dispatched an envoy to Java, demanding tribute. Like the Japanese, the Javanese refused and savaged the envoy.

Furious, the Mongols sent a fleet into the South China Sea starting in January 1293. Despite some successes and even with local allies, the Javans savaged the Mongols.

Despite naval superiority, by August 1293, the Mongols withdrew. The humid, steamy waterways around Java exposed Mongol weaknesses. Their opponents used their expert knowledge of tides, currents, and inlets to overwhelm the Mongols. By the campaign’s end, thousands of Mongols perished.

The Mongols undoubtedly demonstrated their mastery of land-based warfare. Yet try as they did, the seas around China defeated them, checking their almost constant expansion.