The Phoenicians’ success from the late Bronze Age on sat astride an already strong foundation. This base in what’s now Lebanon consisted of three successful trade hubs (Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos). With fewer opportunities inland, they took to the seas. They sailed west across the Mediterranean Sea to establish a loose-knit network of independent city-states, dotting the map with their civilization. The Phoenician era spanned from 1200 BCE to 300 BCE.

Beyond the Mediterranean Sea

While sea commerce provided the bulk of Phoenician success, their network also reached the East. Traders used caravan routes stretching into Iran and India. They reached Mesopotamian cities, such as Babylon or Nineveh. Phoenicians used trading partners instead of colonies or other cities. This inland network further contributed to their success.

Maritime Mastery

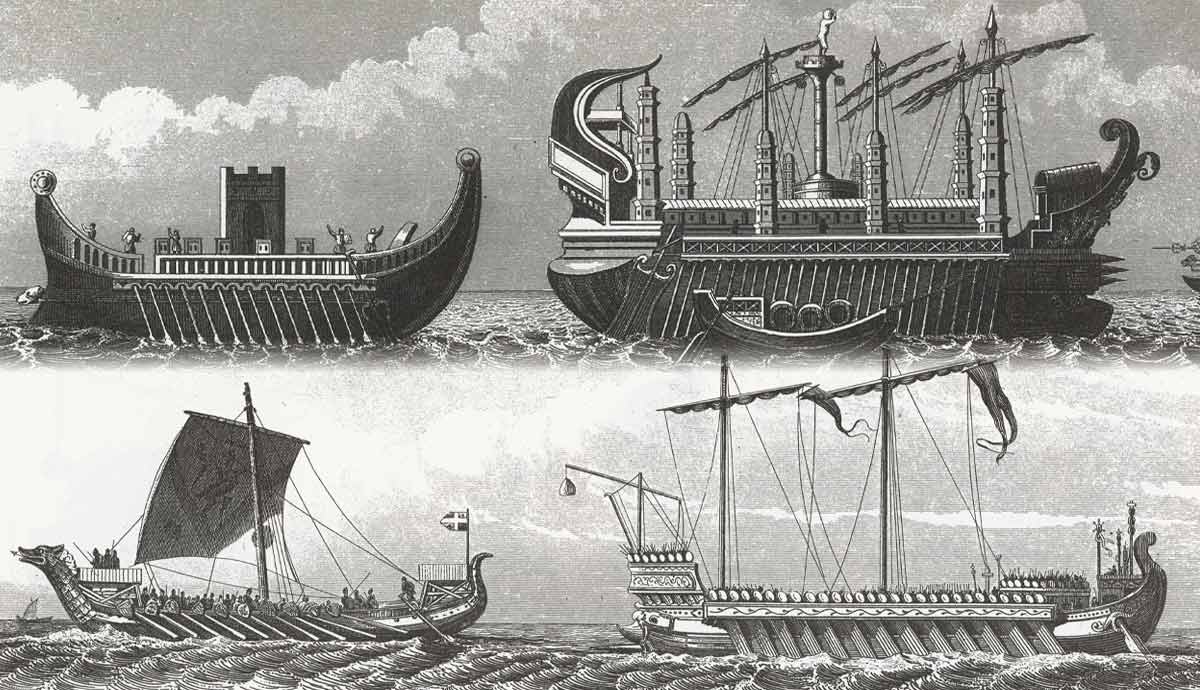

The glue that kept the Phoenician trade network together resulted from their innovation. How? These intrepid sailors developed clever ship designs, used better materials, and mastered celestial navigation. The Phoenician ship designs proved to be durable, technologically advanced, and versatile. Made from cedar, known for its strength and resistance to decay, these deep, curved hull ships had interlocking planks, which increased their durability. Keels provided stability. Besides sailing ships, the Phoenicians used biremes and triremes (two and three-row oared ships), known for their speed and agility.

In an era before instruments like the compass, the Phoenicians navigated using observation, astronomy, and word of mouth. The most crucial guide was the Pole Star (or Polaris), a star that appears in the same spot in the sky. Other skills or knowledge included dead reckoning based on speed and position, landmarks, or even migratory birds.

Only An Economic Empire

Unlike other Classical powers, the Phoenicians had little interest in “empire”. Themselves a loose coalition of city-states, like Tyre, they established regional trading enclaves. Unlike these empires, the Phoenicians saw economic opportunities. Famous settlements included Gadir (Spain) and Carthage, Rome’s eventual foe. Located in strategic locations, these colonies served as trading depots, cultural exchange centers, and diplomatic representations. This trading network spanned from the Middle East to Spain in the far west.

The Phoenicians never developed a unified national identity. Their city-states competed against one another. Each city had self-rule via a king. They paid tribute to larger powers to remain independent, sometimes providing the needed naval expertise.

For trade goods, the Phoenicians traded in many items. Certain goods remained core exports, such as Tyrian purple textiles, cedar and fir lumber, and metalwork. Some areas had distinct tastes, such as Greece or Egypt, which imported wine and olive oil. Agricultural goods, crafted pottery, and raw materials were often traded goods.

By owning the middleman space, the Phoenicians acted as go-betweens. They profited from regional price differences, especially with luxury goods such as gold, silver, or spices. Besides trading, Phoenician-made goods carried a reputation for high quality and popular items.

The Commercial Mechanics and Set Up

The Phoenician trading began before the widespread use of coins via bartering until the late Iron Age, say 450 BCE. Phoenician merchants practiced an ingenious strategy. They’d exchange abundant items in one area, say wine or olive oil in Lebanon, for African or Indian ivory, seen as exotic back home. Profit came from the value difference between the two.

Trade agreements set fixed quantities and values using written contracts, weights, and credit. Trade conducted in Phoenician cities like Byblos or Tyre made them politically neutral spaces. The Phoenicians’ reputation for impartiality added to this reputation.

By 450 BCE, coins became game changers. Phoenician cities minted their coins based on Babylonian weight standards. Coins minted in Tyre or Sidon quickly gained favor due to their purity, quality, and consistent weight, allowing for quicker transactions and simplified trade. Complex trading systems, such as promissory notes, appeared, and more would follow.

A Surprising Legacy

The Phoenician trading network did not collapse at once. Invasions, assimilation, and competition chiseled away at their base. The 332 BCE sacking of Tyre by Alexander the Great is one significant example. Their legacy is quite evident, though. First is the Phoenician alphabet, a simplified twenty-two-character script with only consonants. Unlike something like hieroglyphics, it meant easier records and became the foundation for future languages (Latin, Greek, and Hebrew).

Cities like Carthage thrived long past the Phoenician era, becoming melting pots for different cultures (North African, Iberian, and more!) Standardized coins became another unintended legacy. And not surprisingly, their shipbuilding techniques spread quickly, along with their advanced seagoing navigation, primarily to Rome and Greece.