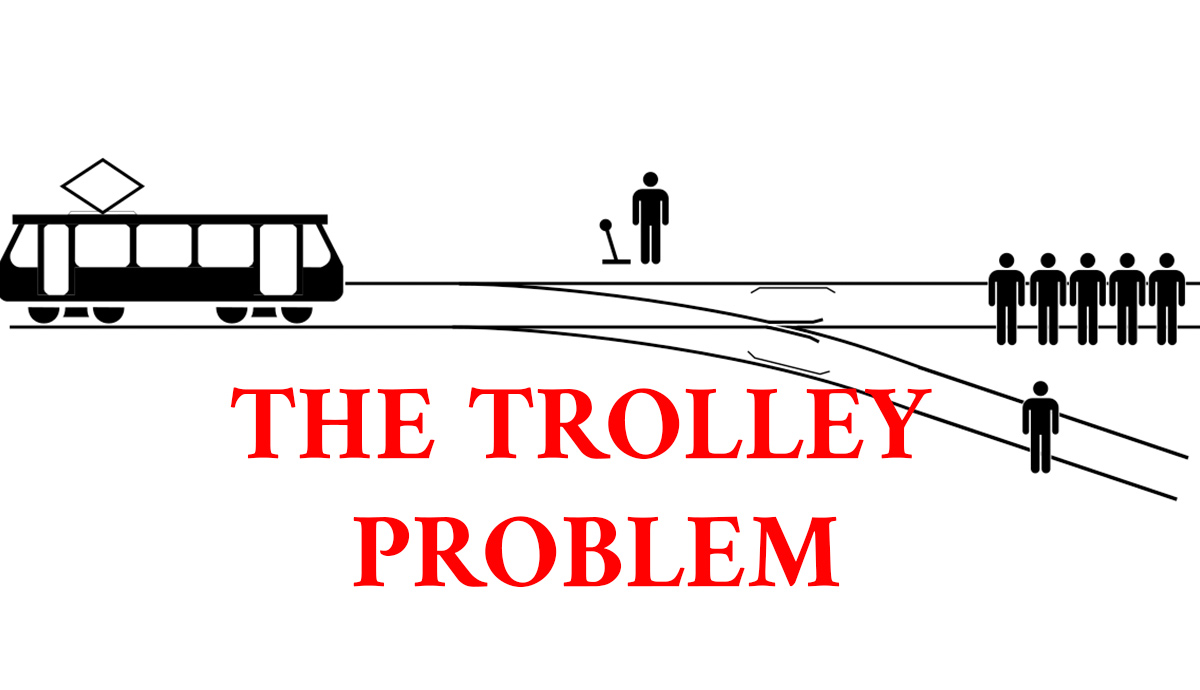

Imagine you are standing near a trolley track. Five people are on the tracks who cannot see the trolley coming towards them. You are standing next to a lever. If you pull this lever, the trolley will switch to a different set of tracks. However, one person is standing on these other tracks as well. What would you do? The Trolley Problem forces us to grapple with some of the thorniest moral issues. Do the ends justify the means—and if so, what are we saying about individual rights or needs?

The Origins of the Trolley Problem

The Trolley Problem was originally introduced by moral philosopher Philippa Foot in 1967. British-born Foot, a pioneer of her time, didn’t develop this ethical thought experiment (hypothetical scenario) for nothing. She wanted to delve deep into some issues around morality.

Central to the Trolley Problem is whether one should let harm befall one person if that means saving many others. Ever since then, this question has fascinated ethical thinkers.

Back then, people were talking more and more about what made dilemmas moral. And this example shows how different ways of thinking about ethics can clash.

She aimed to question whether morality could be neatly divided into strict rules or decisions based solely on results. The issue asks us to think about the tough choices we have to make when our moral duties point in different directions.

Judith Jarvis Thomson, also an influential philosopher, later expanded on Foot’s work. One of her most famous variations is known as the Fat Man problem.

In creating new versions like this one, Thomson made the Trolley Dilemma even more complicated. Now, there were additional details to consider—lots of them—if we wanted to reason well about right and wrong when facts were unclear.

Thomson showed that deciding what to do is not just a matter of applying some general principle like “choose the lesser evil.” It is also necessary to grasp the principles people employ for themselves in making moral choices like these.

The Classic Trolley Problem: A Thought Experiment

One of the original problems regarding trolleys is as easy as it is disturbing. The scene is this: You are standing beside some tracks when you see a trolley hurtling along them.

Looking farther down the line, you notice that five people are trapped on the tracks and can’t move out of the way in time. You happen to be next to a lever.

If you pull this lever, then the trolley will be re-routed onto a different set of tracks. However, if you do this, there is one person further down that line who also won’t be able to move out of the way in time and will be hit instead.

This experiment with thought presents a moral issue. It has troubled not just lay people but also philosophers. Is it right to let one person die if you could save five?

Answering forces us to think about ethical beliefs. Do we say that someone has died because of what we did—or didn’t do? If so, are we responsible for the five others as well?

But the Trolley Problem goes further than asking questions about an interesting (and unlikely) event. It asks us to think hard about how we act when difficult choices have to be made, especially when we can’t be sure what will happen (or who might suffer) as a result.

Doctors, lawyers, and ordinary men and women have all been encouraged by this made-up dilemma to consider why they make the moral decisions they do. They are also asked to reflect on possible outcomes from those choices—in case similar real-life situations ever arise.

Utilitarianism and the Trolley Problem

Utilitarianism, a key concept in moral philosophy, revolves around one simple idea: maximize the good. This theory is based on two things: happiness and harm.

According to utilitarianism, you need to look at the consequences of an action. An action is right if it leads to greater overall happiness or less harm and wrong if it doesn’t.

In the case of the Trolley Problem, there is an answer that can be reached using utilitarianism: pull that lever. By sacrificing one person (which is awful), you end up saving five (which is better), therefore producing the most well-being.

From a utilitarian perspective, saving five lives carries more moral weight than letting one die. When adding things up, it turns out that causing those deaths has better results.

Nonetheless, this view is not free from criticism. It can be claimed that utilitarianism is occasionally excessively emotionless and calculating because it does not take into account people’s individual rights and moral instincts.

For example, is it really true that one should always be sacrificed for the sake of the majority—even if that one is someone for whom we deeply care? Or suppose one feels that pulling a switch is wrong, even though it will produce better consequences.

These criticisms draw attention to an important difficulty with utilitarianism. Although this theory tries to promote the best overall results, sometimes what seems like the just or fair thing to do conflicts with its demands.

Variations of the Trolley Problem

The Trolley Problem has developed over time, giving rise to variations that make our moral calculations even more complex. One such variation is known as the “Fat Man,” a term coined by Judith Jarvis Thomson.

Here’s how it goes: again, you’re by some train tracks. The out-of-control trolley is barrelling towards five people. You can save them by pulling a lever so the trolley switches to a different set of tracks.

But there’s a twist. On this new route stands a man who will stop the trolley—if you push him onto the tracks. This will kill him but save five others.

This version dials up the dilemma of the original problem. Now, you have to actively harm someone (“the Fat Man”) rather than just watch while people die. It becomes not only about what you don’t do (pulling a lever) but what you do—and whether that extra action is too morally costly for many to take.

Yet another interesting version is the “Loop” type. This one makes the trolley go in a circle—meaning it will return to where it started—unless something big enough stops it.

Once again, that something could be a person. Now, the choice is even harder because it is not just about numbers (killing one to save five). Does it matter why we do something, or only what happens?

The idea behind these variations is to show that purely utilitarian thinking has limits. While this theory looks at rules for working out what is best overall, our intuitions (deep-down feelings) say there are times when those rules must not be right. There may be no easy answers.

The new scenarios illustrate that when we make moral decisions, there is more than just calculation going on. We also have to confront values many of us hold dear but prefer not to think about too much because they can make life very uncomfortable.

The Trolley Problem Beyond Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism is not the only ethical framework that can help us consider the Trolley Problem. Different ways of defining right and wrong often give very different answers to the question it asks.

For example, deontological ethics moves our attention from the results of actions (the stuff utilitarians think matters most) to something else entirely: principles.

Deontology takes its instructions from Immanuel Kant’s philosophy. It says we have a duty to do certain things and stick to rules no matter what. An action’s morality does not depend on whether it produces good consequences. All that counts is whether it conforms to a moral law.

From this point of view, someone using deontological reasoning might say this about the Trolley Problem: deliberately killing one person to save five others is wrong, full stop. Here, there is an absolute prohibition on causing harm – meaning that pulling the lever becomes something you must not do.

Conversely, when considering a situation like this, virtue ethics, which dates back to Aristotle, considers the kind of person making the decision. It asks, “What would a virtuous person do?” It does not concentrate solely on results or rules.

Instead of asking whether an action is right or wrong, virtue ethicists check whether it is something a virtuous person would do. They also consider what someone with a good character trait, such as honesty or fairness, would do in that situation.

So, utilitarianism judges act based on their outcomes, deontology evaluates them according to rational moral rules, and virtue ethics refers to the character of the agent.

The Trolley Problem in Contemporary Debates

The Trolley Problem is more than an old philosophical scenario. It can help us deal with today’s toughest ethical challenges. In fact, people are using this classic moral puzzle in areas like self-driving car programming, AI ethics, and public policy.

For example, if your self-driving car has to choose between saving you or pedestrians in a crash, how does it make that call? Engineers and philosophers working on issues such as these find themselves drawn to the Trolley Problem. Here, they seek answers about responsibility and moral guilt. They want to know the worth of different lives in the era of technology.

In contexts beyond technology, the Trolley Problem strikes a chord in debates over public policy. Here, as in whether to allocate healthcare resources one way or another, decisions often boil down to weighing harms against each other.

The same core dilemma—putting a price on human life—is repeated in military strategy, environmental regulations, and many other areas. In this sense, at least, the Trolley Problem shows how important aspects of our moral thinking have remained the same.

Despite its usefulness, however, some people think this example doesn’t go far enough. For instance, there are situations where more than two factors need to be considered. Critics claim that real life often simply doesn’t work like an exam question on paper does.

So, What Is the Trolley Problem?

The Trolley Problem is more than a simple thought experiment. It’s an effective tool for exploring the complexities of moral decision-making.

Whether we look back to its beginnings with Philippa Foot or consider how we can apply it in cutting-edge contexts like AI ethics or public policy, this dilemma forces us to ask ourselves if we can justify sacrificing one person to save five.

This problem reminds people that real-life ethical dilemmas rarely come in convenient packages marked “right” and “wrong.”

Encouraging consideration of various viewpoints may help individuals better understand the situations they encounter (both big and small) and those facing whole societies or regions.