Many underworlds are familiar to us today, such as Elysium and Tartarus of the ancient Greeks, and Heaven and Hell in Christianity. The underworld is a place where people are believed to reside after death, but its appearance can vary significantly between cultures. It is sometimes an underground location, and sometimes there are several chthonic realms. In many civilizations, there are three types of underworlds: an eternal paradise for good people, everlasting damnation for evil people, and a realm in between where the souls await their permanent resting place. Read on to discover five unique underworlds from around the world.

1. Kur, Ancient Mesopotamia

Kur was the underworld in much of ancient Mesopotamia, though it was known by many names over time, including Kigal and Ersetu. Kur was the deepest part of the known universe, usually described as having an entrance in the far west where the sun sets. The Sumerians named many western rivers the “river of the underworld.” Moreover, the entrance, although inaccessible to the living, was a staircase that led to Kur, which was deeper than the Abzu, the freshwater lake that the Mesopotamians believed was beneath the earth’s surface. After the immense set of stairs, the soul would have to traverse through seven gates before entering Kur.

Contrary to many belief systems, the Mesopotamians had one underworld, with no concept of judgment. But Kur was cavernous and bleak, far from a heavenly afterlife. The souls who occupied Kur had nothing to eat but dry dust, so their living relatives were expected to pour libations onto their graves to give them some sort of nourishment.

Correspondingly, the dead with no living family would suffer, with nothing but the dry dust to consume. In some situations, the deceased became so desperate for nourishment that they haunted the living. The fear of dying without children to properly tend their graves encouraged people to have large families.

Upon arrival in Kur, the souls of the deceased stood before the goddess Ereshkigal, the queen of the underworld, who would pronounce them dead, and the goddess Geshtinanna would write down their names. Ereshkigal had several husbands in different myths. In the earliest myths, her husband was Gugalanna, about whom little is known. In later myth, Ereshkigal’s husband was Nergal, the god associated with the dead through warfare. For part of the year, Geshtinanna, also known as Inanna, traded places with her brother Dumuzid, who went down to the underworld in her place. He was a god of agriculture, and when they changed places, the seasons changed.

Demons called Galla also inhabited Kur. The Galla could occasionally be kind and bring gifts to the living, but they were known for forcibly hauling the souls that escaped death back to Kur. There were also individual demons, such as Lamashtu, who caused miscarriages and premature death and supposedly fed on the blood of babies. Pazuzu was associated with plague, but was one of the few supernatural entities who could combat Lamashtu and push her back into the underworld. Pregnant women and mothers of young children often wore amulets depicting Pazuzu to ward off Lamashtu and protect their infants.

2. Duat, Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptian afterlife was called the Duat. It was also believed that the dead needed to take with them whatever they needed. This led to elaborate funerary goods including food, furniture, jewelry, musical instruments, and shabti figurines of servants to work for the dead in the field of reeds. The person also had to be prepared for the transition, with the body embalmed and parts of the soul released by the Opening of the Mouth Ceremony.

The field of reeds or the A’aru was the end goal of the Egyptian afterlife. In the field of reeds, the afterlife mirrored the life one had known on earth, and people were reunited with departed loved ones. Unlike the earthly realm, there was no sickness, no poor harvests, and the land basked in eternal spring, where the deceased lived in peace alongside a pantheon of gods as neighbors.

The Duat was created for the god Osiris when he was killed by his brother Set. His sister-wife Isis used her magic to bring him back to life and impregnate herself with their son Horus, but it was only a kind of half-life, and he could not return to the normal realm. Therefore, Isis also created the Duat for Osiris to rule over, and therefore the underworld.

Funerary texts, such as the Amduat, portrayed the Duat as a parallel realm that one enters before birth, after death, and during sleep. It was also the mysterious space that the sun god Ra journeys through nightly, where he fights with the demon Apophis. The Book of Gates, a funerary text from the late 18th Dynasty, describes the richly imagined Duat, filled with magical beings and landscapes, including lakes of fire and a lion with a hawk’s head.

The Duat was neither good nor bad, but the Egyptians developed the concept of judgment, embodied in the Weighing of the Heart Ceremony, in which the gods weighed the deceased’s heart against the feather of Ma’at. If the heart was equal to or lighter than the feather, the soul passed to the field of reeds. If the heart was heavier, the dead person was devoured by the monster Amut and was condemned to oblivion.

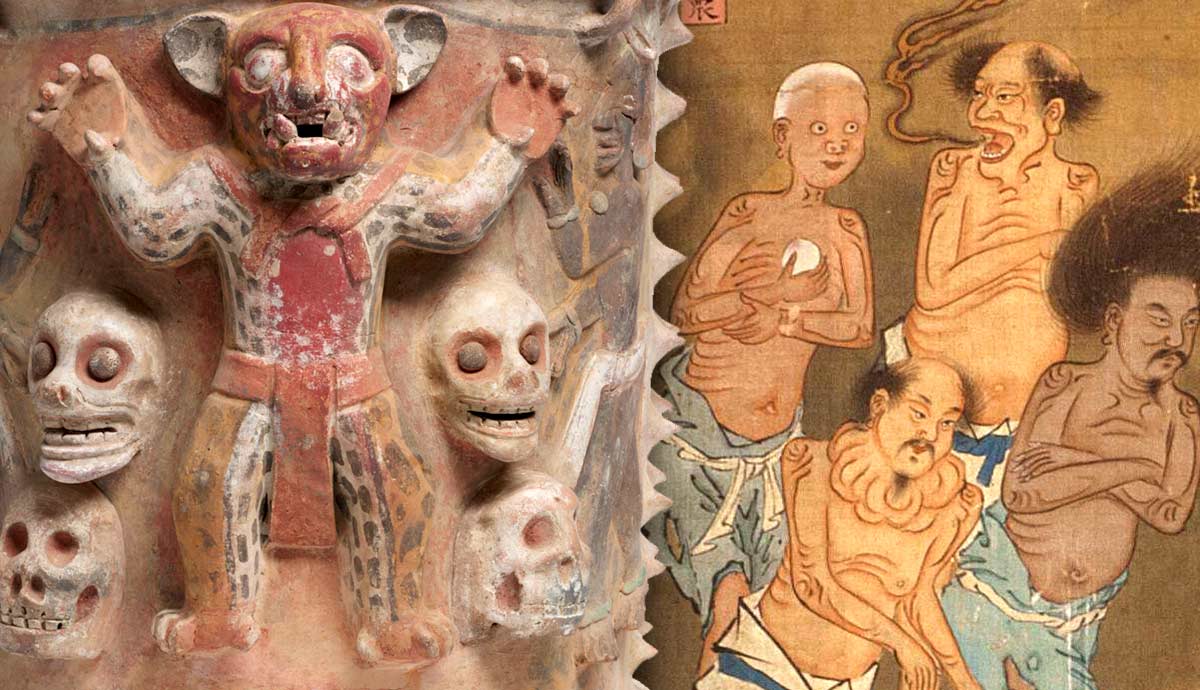

3. Xibalbá, Maya Civilization

The Maya concept of the underworld was distinctly dark in comparison to many other global civilizations. Xibalbá roughly translates to “place of fear,” and the purpose of Xibalbá was to disgrace and humiliate those who could not pass certain tests.

Our understanding of the Maya underworld and its terrors comes primarily from the Popol Vuh of Chumayel, the only known surviving sacred text of the Maya. This is due to the widespread destruction of Mayan codices and writings by the Spanish in the centuries following the conquest. However, the Popol Vuh was translated by Catholic scholars in the 16th century, who demonized Maya religion and added layers of Christian interpretation.

Despite portraying Xibalbá as a place filled with danger and ruled by the malevolent Ajawab, a group of supernatural elite, the Popol Vuh emphasizes that it was not a place of punishment. The Maya did not believe in a system of reward or damnation after death. Xibalbá was simply the next realm where souls continued to reside after death. Xibalbá was accessed by cenotes, natural sinkholes that led to underground pools, and often vast networks of caves. Within Xibalbá, there were multiple sites and structures, notably, the council of the Ajawab, which comprised the houses of torment.

Yet even the journey to Xibalbá was treacherous. Travelers had to pass through three rivers: one river of scorpions, one river of blood, and one river of pus. After navigating the fearsome waterways, the soul had to choose one path from a crossroads that was purposely designed by the Ajawab to confuse them. Paths could lead to houses of torment. These included the Dark House, where the inside was so dark that the traveler could not see in front of themselves, the House of Cold, where a piercing wind blew inside, and the House of Jaguars, where jaguars congregated. There was also the House of Bats, where bats flew out at the exhausted visitor and made horrible shrieking sounds, and the House of Knives or Razors, which was filled with dangerous, sharp blades. In some iterations, there was an additional House of Heat that contained nothing but red-hot flames.

The ultimate ruler of Xibalbá was Ah Puch, meaning “the foul-smelling,” the god of death and sovereign of the underworld. He ruled alongside his wife, the goddess Ixtab, who was the patron of suicide. Yet, it was the Ajawab who maintained order in the underworld’s depths. The twelve Lords of Xibalbá formed a ruling council, led by Hun-Camé and Vucum-Camé, the chief judges of Xibalbá. Other lords had key areas to govern. For example, two were in charge of spilling human blood, two administered diseases, and two presided over the starvation of the human race. The lords appeared in a corpse-like state because they embodied the opposite of life to the Maya.

Concepts like living a virtuous life to escape eternal punishment were not part of the Maya belief system. Everyone had to pass the same tests, except those who died violent deaths, who were spared. Nevertheless, different communities within the Mayan civilization held differing views, with some focusing more on reincarnation, others believing in spirits on earth, and the majority accepting a combination of the three.

4. Diyu, Ancient China

Concepts comparable to the Christian afterlife of Heaven and Hell can be found in Chinese mythology, specifically in the concepts of Tian and Diyu. The Chinese narrative of Tian, or Heaven, predates the New Testament by almost 2,000 years, dating back to at least the Shang Dynasty. In contrast, the notion of Diyu, or Hell, is relatively recent.

Diyu was a supernatural, subterranean place where mortal souls faced trials and tribulations as they repented their mortal sins. Diyu was a maze, consisting of a bewildering labyrinth of chambers and structural levels. The exact number of levels varies in the sources. Some say as few as four, whereas others note at least 18. The general consensus was originally that there were ten levels of hell, typically understood to be the ten Courts of Yanluo.

In this version, Diyu contained thousands of specific hells that were linked to thousands of particular transgressions. Before the individual enters the levels specialized for them, they face a mirror that outlines all the sins they committed in their lifetime. They then pass through the suitable hells, where they receive appropriate punishment.

One such hell was borrowed from Buddhism called Avici, which was the worst level and was home to those who committed the most monstrous offences, such as patricide. Unlike the other chambers in Diyu, once a soul found themselves in Avici, they could never leave and were forced to endure agonizing torture for eternity.

The belief in 18 levels of hell emerged much later during the Tang Dynasty, which saw a greater influx of Buddhist influence. Again, sinners are repeatedly punished for their undesirable actions. If they die (again) during the torture, they regenerate for the torture to continue. The list of abuses one could face was substantial. Some of the most notable included: being lit on fire, being crushed by rocks, being fried in oil, being cut in half, being made to climb trees made of blades, dismemberment, disembowelment, eye-gouging, tooth extractions, being skinned alive, being stung by wasps, being pecked by birds, and drowning in a vat of blood.

Yet, Diyu was not the end. Most aspects of Chinese religious doctrine concerning death uphold the belief in reincarnation. Diyu was a place where the souls prepared for their return to earth and thus had to atone for any wrongdoing committed in a previous life in order to begin anew.

In most versions of the mythology, Meng Po awaits in either the ninth or tenth court of the underworld, offering her famous soup to departing souls. Also known as Aunt or Granny Meng, this deity of forgetfulness is depicted as an old woman in Chinese culture. The potion or soup causes the dead to forget their past lives and recent torture, allowing for a fresh start upon reincarnation. However, on rare occasions, some souls refuse the soup, which results in children who retain memories of their previous lives.

5. Naraka, Hinduism, Jainism & Buddhism

The Buddhist concept of Naraka heavily inspired Diyu, but Naraka is also a firm component of Hinduism and Jainism, both Indian faiths. Therefore, Naraka transcends systems of religious belief to become the general concept of an underworld in India and other Buddhist nations, such as Cambodia.

While the specifics of Naraka differ across faiths, it is generally described as unfathomably hot and located underground. Additionally, reincarnation is a fundamental concept for many Buddhists and Hindus. Therefore, Nakara is typically considered a temporary residence for the deceased before they are reborn.

Buddhist Naraka

In Buddhism, Naraka is linked to karma. Karma is a central concept in Buddhism. The absence of deities in Buddhism naturally places the responsibility for one’s fate at the center of one’s being. It is viewed as a natural law that guides each individual to a fitting rebirth. Torture in Naraka provided an overt incentive for living in accordance with certain rules and beliefs. But Naraka also resets a person’s karma.

A precise timeline of the development of Buddhist Naraka is not possible, as mythology was spread orally until around 100 BCE. However, Naraka was likely a significant part of Buddhism since its conception. Positive deeds led to rebirth in heaven or as a human on Earth, whereas negative actions resulted in reincarnation as an animal, a hungry ghost, or a being in Naraka.

Naraka consists of multiple levels, each inflicting specific forms of torment, with one’s placement determined by the nature of their wrongdoing. After the karma from those misdeeds was eventually exhausted, the soul was free to reincarnate. The hells are made up of eight hot hells and eight cold hells. The cold hells are structured on top of the hot hells, and, theoretically, the torment gets worse the deeper the level of hell. However, most descriptions of the specific levels are abhorrent. The cold hells include such torture as bursting full-body blisters, cracking open frozen skin, and the entire body cracking open because of the cold, which revealed the organs to the cold and then destroyed them.

The hot hells were strategically divided into levels reflective of physical, vocal, and mental transgressions. Punishments include being attacked by flaming weapons, crushed by boulders, having snakes hatch within the body, and being impaled or skinned alive. The eighth hot hell is Avici, associated with the most heinous sins. Avici is essentially an enormous oven where the person is continually falling downwards. The heat is so strong that the body bursts open and muscles snap, but once on their deathbed, the individual is revived, and the process begins again.

Hindu Naraka

A key difference between Buddhist and Hindu Naraka is the presence of deities. In addition, Hindu Naraka was conclusively a place of judgment. The Yamadutas, agents of death, bring the souls of the deceased to the court of Yama, the god of justice and death, who then decides whether they are virtuous enough for Svarga or go to Naraka.

Most Hindu denominations believe that if the deceased remains in Svarga or Naraka for the required period, they are reincarnated. Alternatively, the teachings of Tattavada describe one category of souls who are destined for eternal damnation because of extreme contempt for religion. These souls are called Tamo-yogyas, who resided in the depths of hell forever.

Unlike in many other religions, animals also find themselves in the court of Yama to face his verdict. However, some individuals avoid divine judgment altogether by living extremely righteously, for example, by dying in battle or having a steadfast dedication to charity. These individuals bypass the court and proceed directly to Svarga.

Yet, upon death, the majority of souls find themselves in Yama’s court. In many Hindu mythologies, Yama was the first mortal to experience death and see the pantheon. Consequently, he became the ruler of Naraka and became the patron of death and judgment. In his iconography, Yama is typically depicted as deep blue, riding a buffalo with a noose to apprehend the souls of the deceased.

In some traditions, Yama is depicted with four arms, often holding a mace that emphasizes his fearsome persona, a danda staff that connotes authority, as well as a symbol of breath control and spiritual prowess. In his underworld abode, some Vedic historical conventions portrayed Yama’s living quarters as full of music and also the home of his two dogs, which assist him in tracking down those who are about to die.

Hindu Naraka comprised 28 hells tailored to punish certain crimes. One of these specific hells was called Andhatamisra, where a man who had relations with a married woman would experience the loss of sight and intelligence. Another hell was Kumbhipaka, where an individual who cooked animals alive would be boiled alive without dying for as many hairs as were on the body of each victim. Other punishments included being tormented by snakes, having one’s flesh eaten, being burnt from within, being juiced like sugar cane, being eaten by worms, and being plunged into a river of blood, bones, flesh, fat, urine, and feces.

Ultimately, while the details vary, Naraka is consistently portrayed as a realm of suffering and torment but not eternal damnation. Despite cultural differences, Naraka serves a common moral purpose across traditions: to emphasize the consequences of one’s actions and the importance of ethical living within the framework of rebirth and karmic justice.