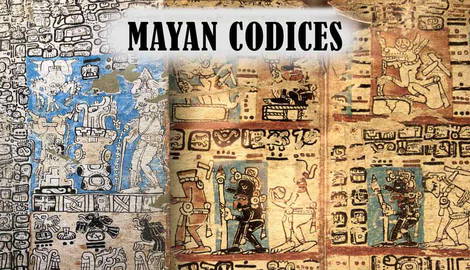

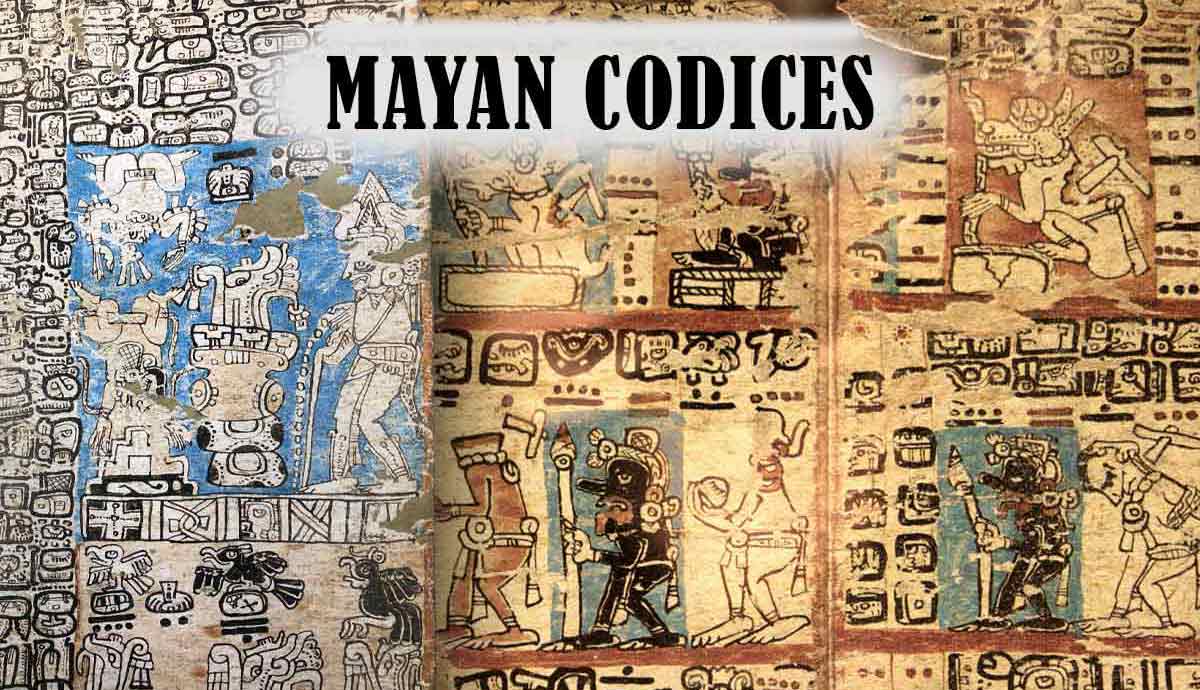

The Mayan Codices are four prehispanic books written before the arrival of Spanish conquistadors. The volumes were created by professional scribes using paper made of the inner bark of a fig tree. With no formal titles, three of the four codices have been named after the cities where they were stored: Dresden, Madrid, and Paris. Together with inscriptions found in temples and monuments, the Mayan codices are a tangible record of their culture, science, society, and politics.

The Written Records of Prehispanic Civilization

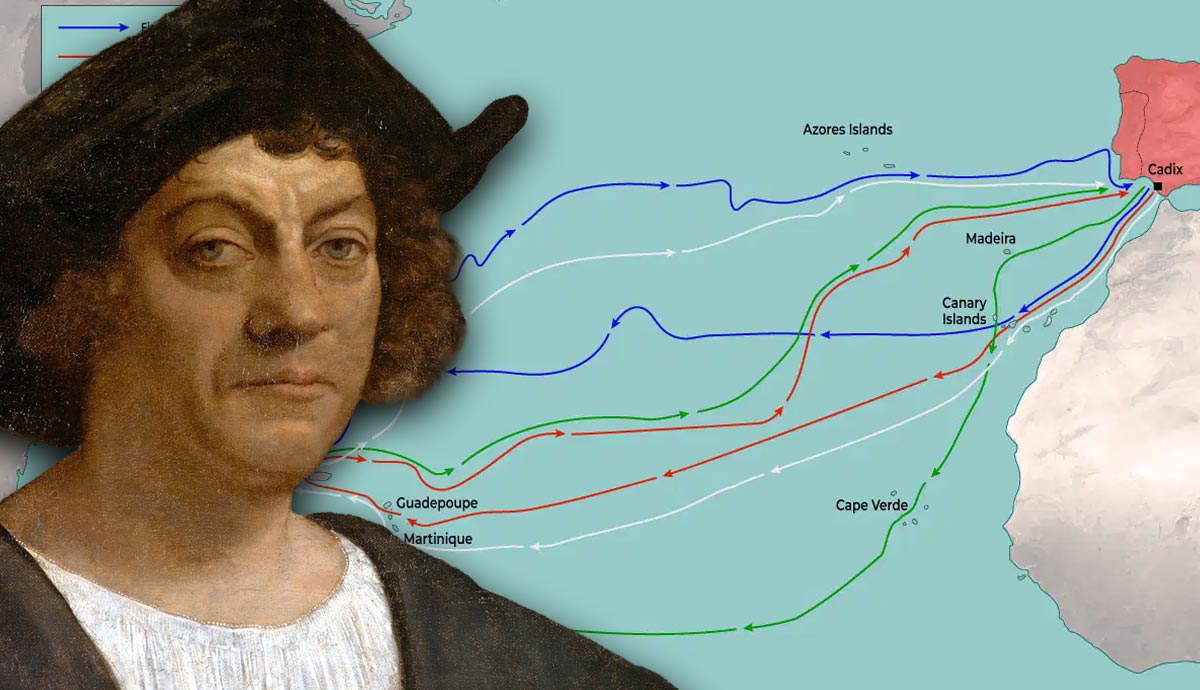

Since the 19th century, different rediscovered Maya monuments, temples, and drawings have been important in developing knowledge about this civilization. The Mayas settled in the Yucatán Peninsula, now Mexico and Guatemala, but expanded to areas of Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador. The earliest evidence of this culture dates back to 2000 BCE; it lasted until the conquest of Hernán Cortés in the early 16th century.

Similar to the Egyptian civilization, knowledge about the Maya comes mostly from drawings and inscriptions left on rocks and ancient papers. The Maya writing method was the most developed in pre-Hispanic America, often compared to those found in Egypt or Mesopotamia. The Maya used inner bark surfaces to inscribe glyphs and different color inks made of carbon soot (black), hematite, lead and insects (red), and plants. Among all these pigments, Maya blue has been studied extensively by researchers because of its long-lasting brightness and unaltered properties. It was known to have been created using an indigo plant and palygorskite, a type of clay.

Diego de Landa’s Destruction of Mayan History

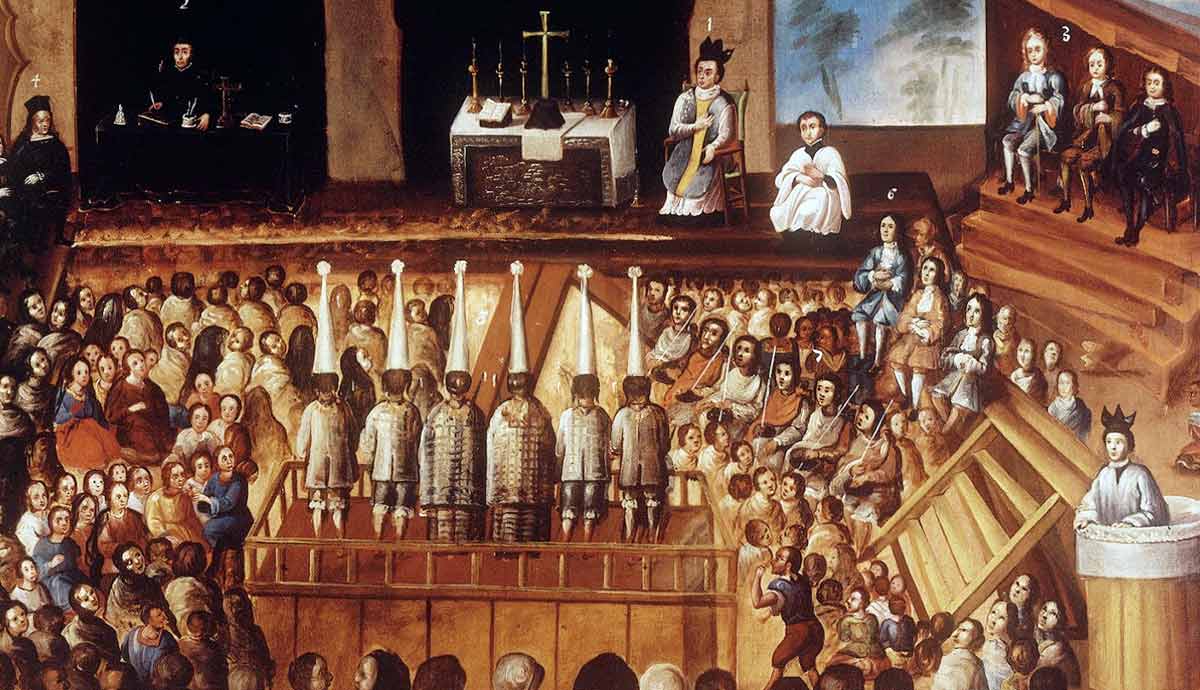

The Maya Codices are the only manuscripts that survived the intense destruction undertaken by Spanish colonizers, as they believed that demons influenced the local knowledge and that it was a threat to the recently introduced Christian faith. For instance, in 1562, Friar Diego de Landa, a Franciscan bishop of the Archdiocese of Yucatan, sent by the Spanish crown to evangelize Indigenous people and one of the first Franciscans to arrive in the Yucatan Peninsula, ordered hundreds of Mayan objects and books be burned because he considered them to be evidence of demonic adoration.

The region was part of Nueva España, under the governance of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile. During this time, Spanish conquistadors were granted the right to the land by the Treaty of Tordesillas, which permitted them to settle in the conquered Indigenous lands of Mesoamerica in exchange for converting Indigenous people to Catholicism and making them subjects of the Spanish Empire.

In 1562, after discovering an Indigenous site of adoration in Mani, the capital of the Tutul-Xiu Maya dynasty, De Landa ordered its destruction and the burning of many codices. This event led to numerous deaths, with some people burnt in their houses, hung on trees, or lost to suicide. De Landa himself recounted in his Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán (Yucatan at the Time of the Spanish Encounter) that the burning of the codices “caused them [the people] much affliction.”

Although the primary mission of the Franciscan order was to protect Indigenous people from the encomenderos (colonists), De Landa pursued the forced imposition of Christian beliefs, often involving physical abuse and torture. De Landa took on inquisitor functions to eradicate any traces of paganism and adoration of idols, often forcefully baptizing people before their conversion. He had not, however, received official authorization from Spain to exercise such actions, which led him to be put on trial in Spain.

Moreover, when the Spanish arrived in the region, the production of the local paper used to produce the codices was banned, and it was replaced by European paper. This was used, for instance, to create the Aztec Codex Mendoza (circa 1541).

The Dresden Codex

The Dresden Codex is the oldest of the Maya codices (11th-12th centuries) and the oldest surviving book written before the arrival of the Spanish. It arrived in Spain after being sent to King Charles V by Hernán Cortés. Later, the Royal Library of Dresden obtained it in 1793 from a private owner in Vienna. During World War II, the Codex suffered in the flooding resulting from the bombings of Dresden in 1945.

It is believed that the Dresden Codex was written and drawn by the peoples of the Yucatán Peninsula because different symbols in the codex are also present in monuments of the region. The codex contains information related to local history and calendrical and astronomical knowledge related to the movements of the moon and Venus. It has also been important in deciphering Maya hieroglyphs.

The codex has been reproduced several times by figures such as German naturalist and geographer Alexander von Humboldt in 1810, Italian painter Agostino Aglio for Irish antiquarian Lord Kingsborough in 1826, German historian Ernst Förstemann in 1880, Mesoamerican archaeologist J. Eric Thompson in 1972, British Mayanist Ian Graham in 1959, and the Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt in Graz, Austria, in 1975. The codex is available for download from the Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies FAMSI website and is currently exhibited in the Saxon State Library in Dresden, Germany.

The Madrid Codex

Also known as the Codex Tro-Cortesianus, it was split in two when transported to Europe. The first part was rediscovered in 1866 by French Catholic priest and ethnologist Brasseur de Bourbourg in the archive of Spanish lawyer Juan de Tro y Ortolano. De Bourbourg also discovered Diego de Landa’s book Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán. The first part of the codex is also known as the Codex Tro because of its former owner.

The second part of the codex was owned by a Spanish collectionist named Juan Ignacio Miró, who, after being unable to convince the British Museum and the Imperial Library of Paris to buy the piece, sold it to the Archaeological Museum of Madrid in 1875. The second part of the codex is known as the Codex Cortesianus because it is believed that it was also Cortés who brought it to Europe.

In 1888, the French ethnologist Léon de Rosny discovered they were part of the same piece, which was ultimately dubbed the Codex Tro-Cortesianus. The piece is exhibited at the Museo de América in Madrid, Spain. The codex was created between 1250 and 1450, and its origins are debated between the regions of Campeche and Tulum. Similar to the Dresden Codex, this piece holds information about calendric events, horoscopes, and astronomical tables. Representations of agriculture, hunting, apiculture, and disease are also present.

The Paris Codex

Also known as Codex Peresianus, this manuscript originated in the Yucatan Peninsula around 1250-1450. The National Library of Paris acquired it in 1832. However, French ethnologist and orientalist Léon de Rosny, who found it in the aforementioned library in a pile of abandoned documents next to a chimney, formally exhibited it to the world in 1859. The document is made of 22 accordion-folded pages, which when unfolded reach 1.45 meters (4 ft. 9 in.) in length. The manuscript is believed to be a copy of an original 3rd-9th century codex made during the 13th century.

The codex contains information about the Maya’s religious rituals, prophecies, and cosmogony. It also contains a calendar of 364 days, similar to the one used today. An online version of the codex can be found in the online library of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. The physical copy is stored in a fragile state in the institution’s installation in Paris.

The Grolier Codices

Also known as the Codex Maya of Mexico, this collection illustrates the figures of different deities and is believed to have been used as a calendar to calculate Venus’s movements, a theme also present in the Codex Dresden. It dates from the 13th century and was discovered in the late 1960s when a collector named Josué Sáenz traveled to the region of Palenque. There, he found eleven manuscript fragments. In 1971, he took them to the Grolier Club of New York, a private society of bibliophiles, where they were exhibited.

Some researchers, however, have not been wholly convinced of its authenticity because of its pictographic style, which differs from the other three codices, and because of the absence of Maya blue ink. Despite some hesitation, it is widely considered authentic today.

The Maya Today

The Maya codices remain historical pieces that reveal the ancient history of a civilization that, although diminished during colonial times, still survives in Mexico. Despite the process of mixing different ethnicities after the arrival of Europeans and African slaves during the 16th century, there are still 10 million Maya people living in the areas of Guatemala, Mexico, Belize, and Honduras today. Many live in conditions of poverty and are subjected to difficult social conditions in their countries.

In contemporary Mexico, Mayans live in Yucatán, Campeche, Quintana Roo, Chiapas, and Tabasco. These communities often dedicate their lives to agriculture, fishing, and handicrafts. Their religious practices present syncretisms with the Catholic religion, expressed, for instance, in their Easter celebrations.

Scientists are still deciphering the Maya codices, reconciling the inscriptions with archaeological research about Mayan architecture and found objects. While these artifacts provide valuable insight into Mayan history, it’s important to remember that the Mayan culture is still alive in the traditions, language, and beliefs of the surviving communities in the region.