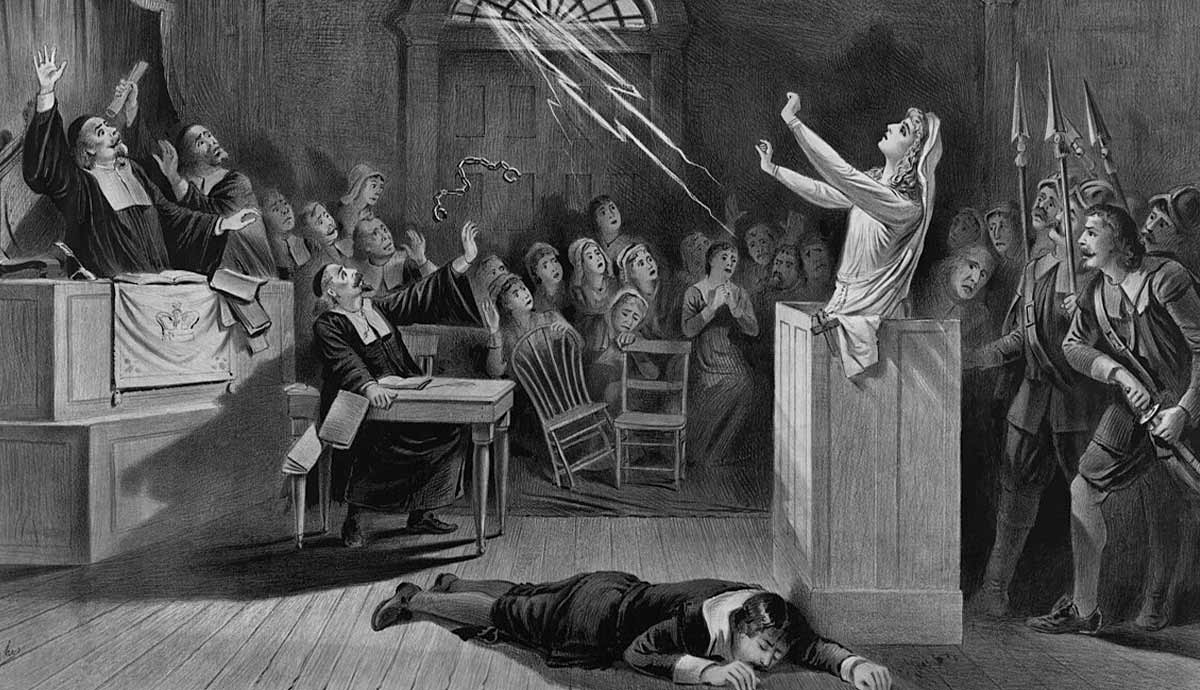

In early 1692, in the village of Salem, Massachusetts, a group of young girls began exhibiting strange and disturbing behaviors, including convulsions, screaming, and fits. Unable to explain these symptoms medically, local ministers and villagers suspected witchcraft. Under pressure, the girls accused several women in the community of bewitching them. The accusations quickly spread, fueled by fear, religious fervor, and long-standing local tensions. The colonial justice system, lacking proper evidence standards, accepted spectral evidence such as visions and dreams as valid testimony. This led to a wave of hysteria, over 200 accusations, and the execution of 20 people before the trials ended in 1693. While the story of the Salem witch trials rightly focuses on the victims, who were the accusers, and what happened to them when the trials ended?

Elizabeth Parris & Abigail Williams

The first two girls to claim they were afflicted by witches were Elizabeth Parris and Abigail Williams, aged nine and eleven, respectively, in 1692. Elizabeth was the daughter of Samuel Parris, Salem’s pastor, who promoted devout anti-witchcraft ideology, while Abigail was his niece.

The accusations began after Elizabeth “Betty” Parris and her cousin Abigail engaged in occult practices, including fortune-telling with a Venus Glass. These activities coincided with episodes of unexplained illness and erratic behavior, which local physician William Griggs failed to diagnose. The community believed the symptoms were a sign of witchcraft, and a neighbor, Mary Sibley, suggested that Tituba make a “witch’s cake” to identify the culprits. When the cake failed, Tituba was accused by Elizabeth of being one of the “Evil Hands” afflicting her.

The two girls implicated two other marginalized women, Sarah Osbourne and Sarah Good. Probably looking to escape punishment herself, Tituba confirmed the accusations against the other two women. While Tituba escaped death, Osbourne and Good were both later executed.

After the trials, Elizabeth was sent away to live with family, and her afflictions ceased. She never recanted any of her accusations. In 1710, at the age of 27, Elizabeth married Benjamin Baron, a tradesman, and had four children before his death in 1754. Betty passed away on March 21, 1760, in Concord, Massachusetts, at the age of 77, having lived a rather comfortable life. Abigail Williams, on the other hand, disappeared from the historical record shortly after the trials. Her fate is completely unknown.

Samuel Parris

Samuel Parris, born in London to a modest and religiously nonconformist family, emigrated to Boston in the 1660s and briefly attended Harvard. Following his father’s death, he inherited a sugar plantation in Barbados, which he later abandoned after a hurricane in 1680. Returning to Boston, he married Elizabeth Eldridge and brought his enslaved servant, Tituba, with him.

Dissatisfied with his financial prospects, Parris entered the ministry, becoming Salem Village’s minister in 1689. His tenure was marked from the outset by community discord and financial disputes. In 1692, his daughter Elizabeth and niece Abigail accused Tituba of witchcraft, prompting Parris to beat a confession out of the elderly woman. This act would become the catalyst for the Salem Witch Trials.

In a 1692 sermon, Reverend Samuel Parris likened the presence of evil in the church to the betrayal of Christ, inciting villagers to identify each other as witches, often individuals opposed to Parris and his allies, notably the Putnam family. After the hysteria died down, Parris’s active role in the prosecutions led to formal charges from his parish in 1693. While he issued a public apology, he was subsequently vindicated by a church council.

Following a legal dispute over land and unpaid salary, Parris resigned from Salem in 1696. He remarried to Dorothy Noyes in Sudbury, moved to Concord, and preached in various towns in Massachusetts until his death in 1720.

Thomas Putnam

Thomas Putnam, born in 1652, was a prominent resident of Salem, the son of Lieutenant Thomas Putnam Sr. and Ann Holyoke. He married Ann Carr, with whom he had twelve children. Putnam served as a Sergeant in King Philip’s War and held the position of parish clerk. Nevertheless, he was largely excluded from family inheritances, which fostered resentment, particularly toward his half-brother Joseph, who married into the rival Porter family. Historians believe these familial and social tensions likely influenced Putnam’s zealous participation in the witchcraft accusations that engulfed Salem.

Putnam was the first to pursue legal warrants against alleged witches. Thomas, his wife, and daughter collectively accused over 100 individuals, many of whom were affiliated with the rival Porter family. In 1699, Putnam died at age 46 from an unidentified illness, followed two weeks later by his wife, leaving their surviving children orphaned.

Ann Putnam Jr.

Ann Putnam Jr was born in 1679 in Salem, the eldest daughter of Thomas and Ann Putnam. At just 12 years old, Ann joined a group of girls, including Elizabeth Parris and Abigail Williams, who claimed to be afflicted by witchcraft.

Mercy Lewis, a fellow accuser, worked in the Putnam household as a servant, while another girl, Mary Walcott, was likely Ann Putnam Jr.’s closest companion. These three became the first individuals outside the Parris household to claim affliction by witchcraft. In March 1692, Ann reported her symptoms and became one of the most prolific accusers, responsible for naming 62 individuals.

Ann’s life was turned upside down after her parents’ deaths in 1699. Ann, then unmarried, assumed responsibility for raising her nine surviving siblings. In 1706, under the guidance of Reverend Joseph Green (Samuel Parris’s successor), Ann composed a public confession acknowledging her role in the Salem witch trials.

Ann, now aged 27, was presented before a large congregation. Her statement expressed remorse for the wrongful accusations she had made in childhood, particularly against Rebecca Nurse, who had been executed. Yet, Ann did not take all the blame and attributed her actions to satanic deception. Her reputation somewhat recovered before her death in 1716.

Mercy Lewis

Mercy Lewis had experienced profound trauma before the Witch Trials. As refugees of King Philip’s War, her family initially sought refuge in Casco Bay, New England, following a violent Native American attack. Among the survivors was Reverend George Burroughs, a former Salem minister. After briefly resettling in Salem, the Lewis family returned to Casco Bay, where a second attack in 1689 claimed the lives of Mercy’s parents, leaving her an orphan.

Subsequent raids also killed Mercy’s extended family, including her grandparents. By age 14, she entered service in Burroughs’ household and, by 1691, had relocated to Salem. There, Mercy became a servant in Thomas Putnam’s home. While in service, Mercy Lewis formed close ties with Ann Putnam Jr. and Mary Walcott.

In April 1692, Lewis claimed Satan appeared to her, first offering riches, then manifesting as Reverend George Burroughs, promising dominion if she pledged allegiance. Though no formal medical records exist, Lewis reportedly suffered seizures, including a violent episode on May 7, 1692, allegedly triggered by Burroughs when she refused to sign the “Devil’s Book.”

In addition to the accusation, Mercy also obstructed Mary Esty’s release and acquittal. Esty was a respected and devout member of the Salem community, unexpectedly accused of witchcraft in 1692. During her examination, afflicted girls mimicked her movements and claimed spectral assaults. Esty notably defended herself with dignity, denying any pact with Satan. Though briefly released from prison in May, Mercy’s renewed accusations led to her re-arrest. Her trial concluded with a conviction, and she was executed on September 9, 1692.

Very little is known about Mercy after the trials. Initially, she moved to Boston to live with her aunt, where she gave birth to a son out of wedlock. Mercy married in 1701, but then disappears from the historical record.

Mary Walcott

Mary Walcott, born in Salem Village to Captain Jonathan Walcott and Mary Sibley, was 17 when the witchcraft hysteria began. Her familial connections placed her at the heart of the trials. Her aunt, Mary Sibley, initiated the infamous “witch cake” ritual by instructing Tituba and John Indian to feed a cake made with urine from afflicted girls to a dog, an act believed to reveal the identity of witches.

Alongside Ann Putnam Jr. and Mercy Lewis, Mar Walcott claimed to suffer supernatural torments and named numerous individuals as witches. Her testimonies contributed directly to the prosecution and execution of several accused, including Mary Esty, Giles Corey, and Bridget Bishop.

After the trials, Walcott married Isaac Farrar in 1696, with Reverend Parris officiating. She eventually relocated to Sutton, Massachusetts, where she lived out the remainder of her life. Her story highlights some of the dynamics at play in Salem. As someone of lower social standing, Mary aligned herself with the affluent Putnams and, despite the chaos, lived a long and stable life.

Elizabeth Hubbard

Elizabeth Hubbard, also 17 when the trials began, was a maidservant of Dr. William Griggs and began experiencing episodes shortly after his examination of Abigail Williams and Betty Parris. Due to her age, Elizabeth was permitted to testify under oath, and her dramatic courtroom behavior, including frequent fits, lent credibility to her accusations. She filed 40 complaints and testified 32 times, contributing to the arrest of 17 individuals, 13 of whom were executed.

Elizabeth’s life after the trials remains uncertain. Historians suggest she may have relocated to Gloucester, Massachusetts, married a man named John Bennett, and had four children. However, this identification is speculative, based on a marriage record for an Elizabeth Hibbert rather than Hubbard.

Mary Warren

Mary Warren was both an accuser and accused. As a servant in the household of John and Elizabeth Proctor, Warren initially joined the circle of afflicted girls in early 1692, claiming to experience fits and spectral visitations. Her symptoms were met with skepticism by John Proctor, who threatened her with violence and insisted she return to work.

However, Mary’s temporary withdrawal from the hysteria drew suspicion. After she suggested that the afflicted girls might be feigning their experiences, she was accused of witchcraft herself. On April 18, 1692, she was formally arrested. Under interrogation, Mary resumed her afflictions and confessed to witchcraft, implicating others, namely her employers, the Proctors. The confession under duress illustrates the intense psychological and social pressures faced by individuals caught in the trials. Her shifting allegiances underscore the volatile nature of the proceedings. She was released from prison in June 1692, but her life after the trials remains uncertain.