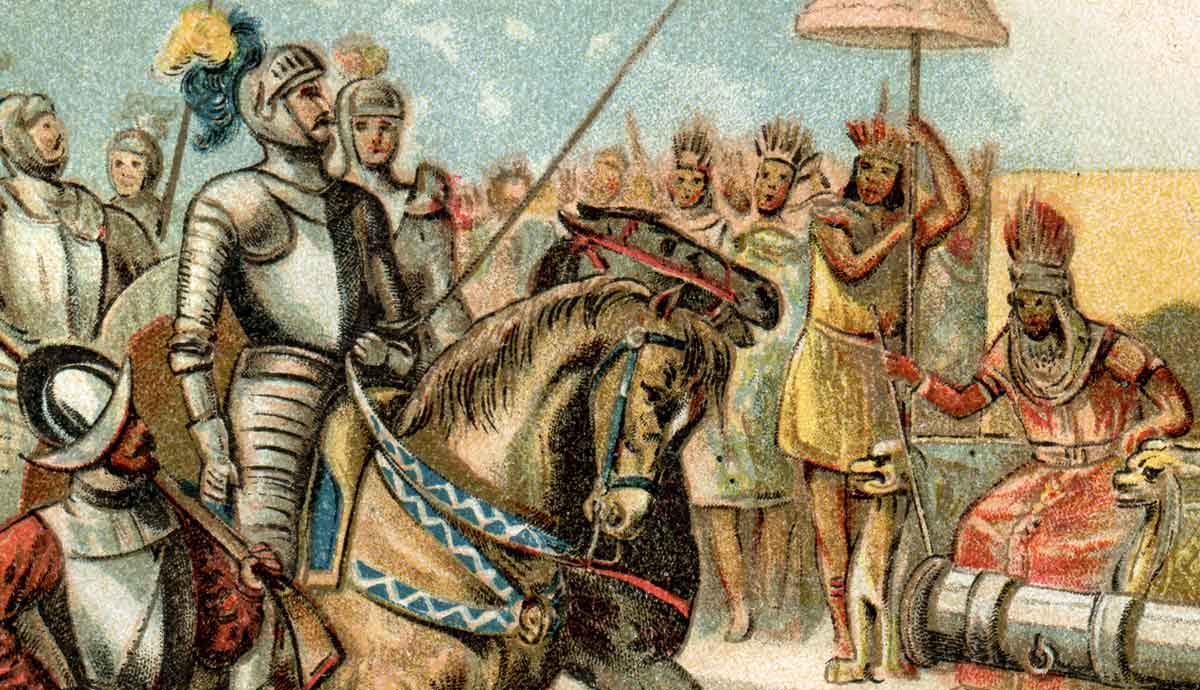

The place: Tenochtitlan, a metropolis built in the middle of a lake, with floating islands supported by piles. The date: November 1519. Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and his men must have been astonished. Tenochtitlan had more inhabitants than London or Paris and, in many ways, was better organized. Standing before Cortés, a 34-year-old university dropout, was the most powerful emperor in the Americas, Moctezuma II. “Gazing on such wonderful sights, we did not know what to say, or whether what appeared before us was real,” wrote Bernal Díaz, one of Cortés’s companions.

The Most Consequential Meeting in History

This moment was remarkable—an entire, advanced civilization had flourished without the rest of the world knowing. But none of those present had any idea of its true implications. When Cortés met Moctezuma—and no, they didn’t hold or shake hands as some images suggest; no one was allowed to touch the emperor—the descendants of those who, at the dawn of history, migrated eastward from the Fertile Crescent and those who moved to the other side of the world were finally reunited. Globalization had begun. It was “the most astonishing encounter in our history,” as semiotician Tzvetan Todorov put it.

Did Cortés, the failed law student, the farmer, the adventurer, kneel in reverence before the divine monarch, awestruck by the almost supernatural scene of the floating city with snow-capped volcanoes in the background, accompanied by his 500 Spaniards but surrounded by more than a quarter of a million of Moctezuma’s warriors? Not at all. In less than two years, the great Tenochtitlan, its temples and causeways, were in ruins, its inhabitants on their knees, and Cortés was the master of it all.

To paraphrase historian and geographer Jared Diamond, guns, germs, and the Indigenous allies who helped Cortés played a role in the success of the Spaniards. But it’s also true that, more than once, the conquistador and his men were just a hair’s breadth away from defeat—and from being dragged up the nearest pyramid to have their hearts ripped out and offered to the god Huitzilopochtli. Maybe if the Mexica had reacted more quickly, more brutally, maybe if they hadn’t been so cautious, things would have turned out differently. And world history would have, to put it mildly, taken an abrupt turn.

What if Moctezuma had not just defeated the Spaniards, but annihilated them, wiping out any trace of their presence from the continent?

The Sad Night

It may have all started on June 30, 1520, a moment etched into the memory of every Mexican child as the infamous Noche Triste, or “Night of Sorrows.” For the first and only time, Spanish forces faced total defeat—almost annihilation. The Mexica had every reason to be furious: in the absence of Hernán Cortés, who, though ruthless, wielded diplomatic tact, one of his captains, Pedro de Alvarado, a blond Spaniard the Mexica nicknamed “the Sun,” committed a massacre in the heart of Tenochtitlan. The Mexicas had been peacefully celebrating the Toxcatl Festival at the Templo Mayor when the bloodshed began.

A survivor later described the horrific scene to Bernardino de Sahagún:

“Suddenly, they began to slash and stab the people. They cut them down with swords, wounding them deeply. Some were attacked from behind, immediately falling to the ground with their entrails scattered. Others had their heads severed, cleaved right off. Some were struck in the shoulders, their bodies ripped open. They cut others in the thighs, or the calves, or straight through the abdomen. Intestines spilled everywhere. Some, in vain, tried to flee, dragging their guts behind them, tripping over their own entrails.”

When Cortés returned to the city, he ordered his men to flee under the cover of darkness, but they were discovered, and a brutal battle followed. By dawn, hundreds of Spanish and Indigenous bodies floated in the waters of Lake Texcoco. Cortés had lost his treasured city, and the defeat was near total. Legend says that, crushed by his misfortune, he sat beneath a towering ahuehuete tree and wept bitterly—the origin of the name “Noche Triste.”

Interestingly, this so-called “Tree of the Sad Night” could still be seen in Mexico City until recently, along the Calzada México-Tacuba roadway. What remained of it was destroyed in a fire in 1980. Today, only a colossal, charred stump stands. In 2021, the Mexican government renamed it the “Tree of Victory.” The avenue is now called Calzada México-Tenochtitlán.

This renaming—from “Sad Night” to “Night of Victory”—reflects Mexico’s way of reinterpreting its past. It’s a clear sign that the collective subconscious still holds onto the notion of an Aztec victory, even in retrospect. And that possibility was more real than ever on that fateful night, as Cortés, battered and defeated, gathered his forces to ultimately make another, this time successful, attempt to besiege the powerful Aztec capital.

The Defeat of Hernán Cortés

Now, instead, imagine this: that symbolic tree standing tall today in 2024, in a city still called Tenochtitlan—a name many now wish to restore—at a square that has always been known as the Victory Square. Imagine history books pointing to it as the place where European colonization was checked. Imagine that in 1520, Cortés was captured and sacrificed atop the tallest pyramid the morning after Noche Triste. The history of modern Mexico—and indeed the entire world—would have unfolded completely differently.

Would Cuitláhuac, the new Aztec emperor, have been content knowing Cortés had fled, making the painful journey back to Veracruz, only to sail back to the Caribbean for a second chance? Hardly. Cuitláhuac was already organizing an army of half a million warriors, far greater than all the Spanish forces stationed in Cuba. (Tragically, Cuitláhuac died of smallpox weeks later.)

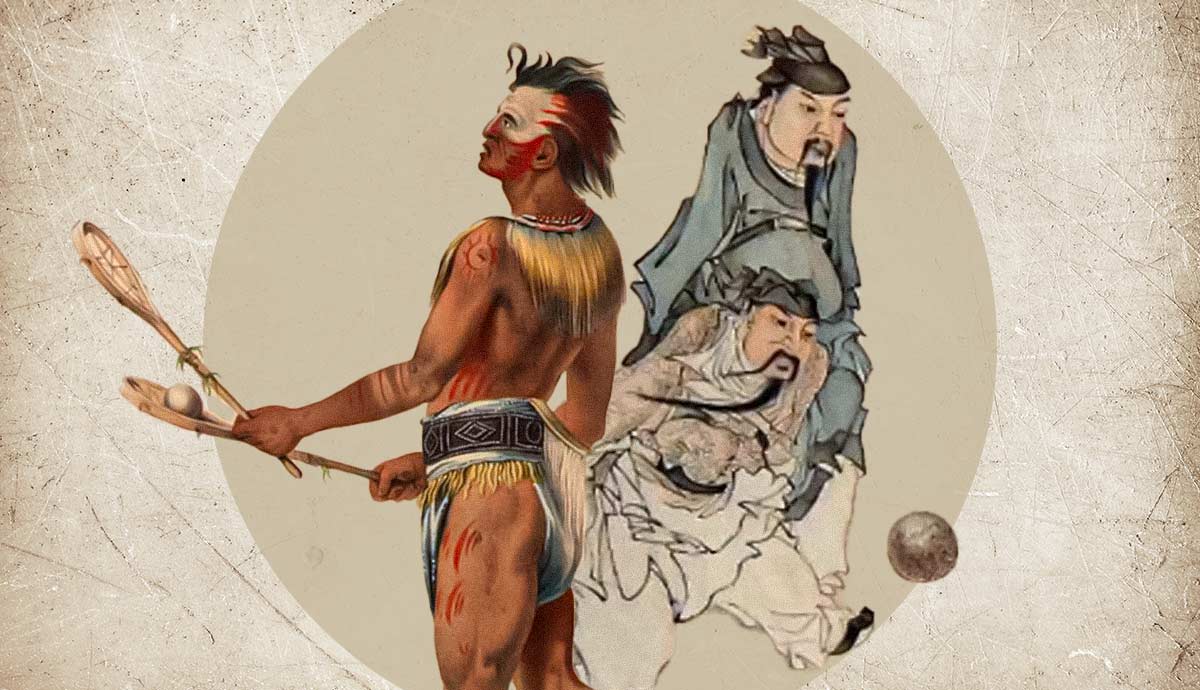

Revenge would have come swiftly. The Mexica were far from ignorant. They would have adapted to the new mechanics of warfare, adopting Spanish swords and forming a powerful Indigenous cavalry just as North American tribes later mastered horseback warfare. They might not have forged European-style firearms, but they could have easily incorporated remaining Spanish arms into their arsenal. In fact, their Empire already had the necessary materials to make gunpowder and forge metals—more than one Spanish defector could have taught them how.

The Aztecs Retaliate

Could a strengthened Aztec empire have commandeered Cortés’s thirteen brigantines, armed with cannons, left behind on Lake Texcoco? Could they have used them not only to destroy the colonizers in the Gulf of Mexico, but to invade Cuba and wipe out Spanish settlements? It’s plausible. The Mexica were no strangers to water; after all, they built a magnificent city on a lake. A Caribbean naval war, akin to Mediterranean conflicts, might have unfolded.

However, based on their culture, a more likely outcome would have been a fortification of defenses and the embrace of isolationism. This could have delayed European presence for at least a century, perhaps, reducing the spread of disease and limiting Christianity’s influence.

Meanwhile, the news of the Inca Empire’s fall at the hands of Pizarro would have eventually reached the Mexica, fostering a stronger pan-Mexican unity and a more determined defense of their borders. Europe, upon learning of Cortés’s destruction, would have reeled in shock. Spain’s conquest efforts might have been halted entirely, and the Aztec Empire would have gained a newfound respectability.

No empire, however, could escape globalization forever. But perhaps the Mexica—and all of the Americas—might have resisted longer, on their own terms. Would this have led to more equitable relations—robust trade instead of subjugation? Perhaps. More importantly, without the immense wealth of Mexico flowing into Spain for centuries, capitalism might have been restrained, and Europe would be less advanced today. Without a continent to evangelize, Catholicism might have remained confined to the Mediterranean, while an Indigenous religion continued to thrive in the Americas, with millions still speaking Nahuatl, the language of the ancient Mexica.

Beyond Heroes and Villains

Mexico would exist today in a similar, yet vastly different form—a militarily powerful, even territorially expansive state, from Oregon to Panama. And certainly, a strong Aztec empire would have led to a smaller United States with less room for expansion.

Spain and Europe, no doubt, would have lost much without the conquest. Consider that the Americas might have lost out as well. As brutal as the clash between these two worlds was—personified in the meeting of Cortés and Moctezuma on the shimmering waters of Tenochtitlán—the result might ultimately be considered a step forward for humanity. It enriched the cultures, economies, art, and gastronomy of both continents.

It’s impossible to know how history might have unfolded had it followed a different path. But in considering the possibilities, it remains essential to resist the simplistic view of the Indigenous as inherently noble and the Spaniards as inherently evil. The Spanish Conquest, or Indigenous Resistance, as it’s now referred to by the Mexican government, was driven by forces far greater than its players.