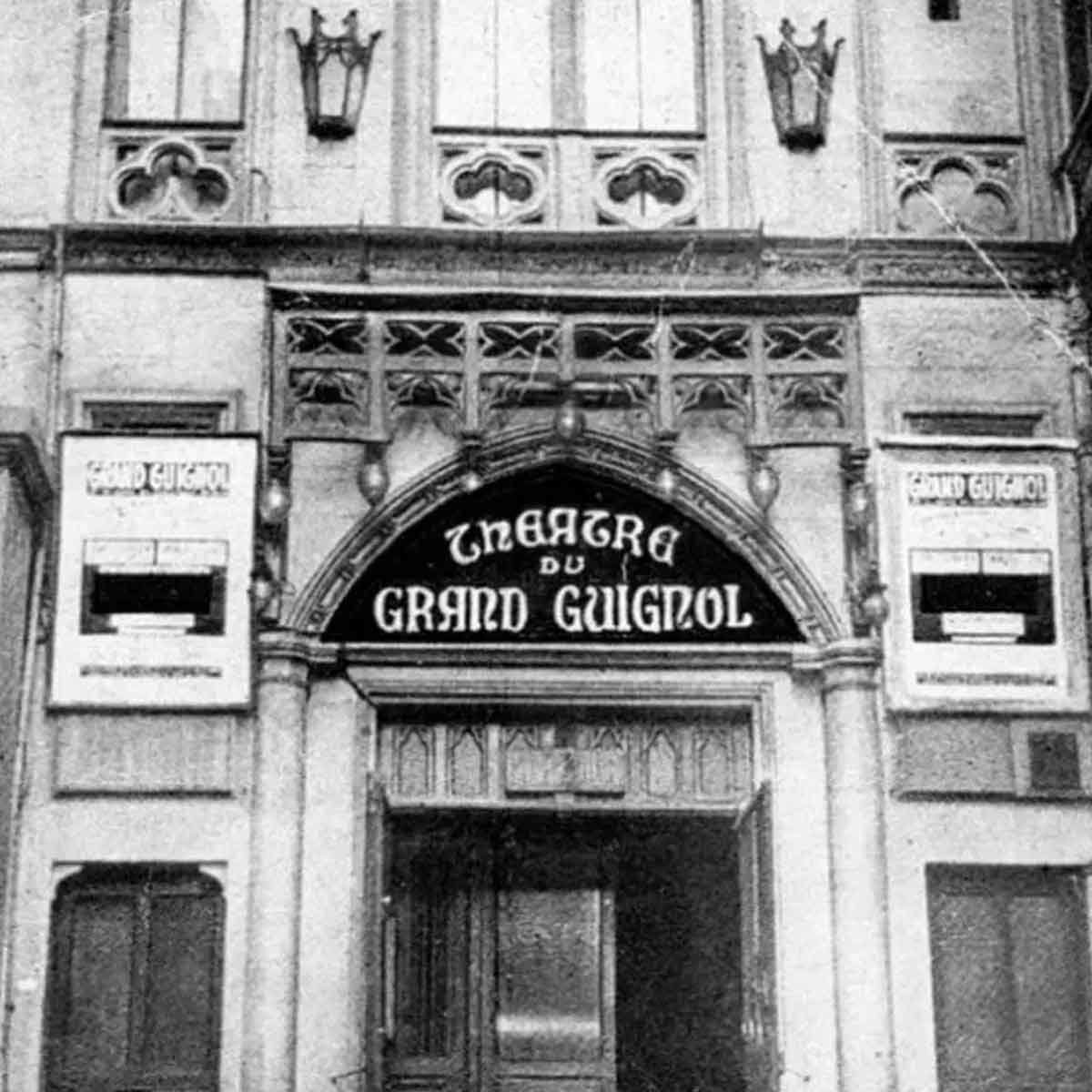

For six decades, The Grand Guignol in Paris kept the title of the most shocking, provocative, and fashionable theater in Europe. Known for its explicit violence on stage and the overwhelming atmosphere of horror, it was innovative and provocative. Read on to learn more about the plays staged at the notorious Grand Guignol Theater and the writers who created them.

The Grand Guignol Showers

Over the sixty years of its existence, Le Grand Guignol scared, shocked, and stirred public scandal. That shock value, however, made the theater unwelcome in the majority of high-brow research projects. Unfairly dismissed as crude entertainment, The Grand Guignol was greatly undervalued as a tool of social commentary, an experiment in narrative construction, and a revolutionary way of communicating with the audience.

Oscar Metenier, the theater’s founder, revolutionized the narrative structure of its performances. Instead of one several-act play, he introduced up to five short pieces per evening. His most significant addition, however, was the order of those pieces: calling them hot and cold showers, Metenier decided to alternate comedies with dramas, achieving maximal emotional impact.

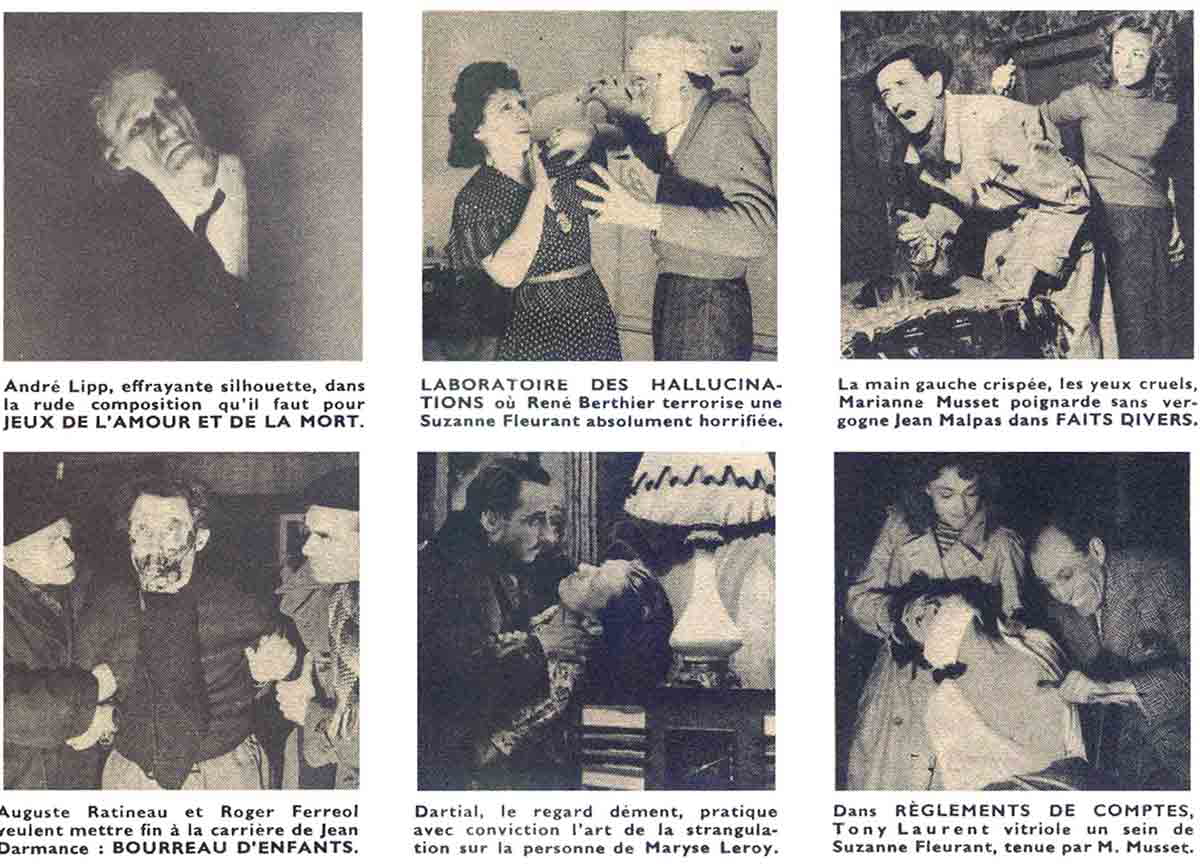

After the theater’s owners changed and the degree of shock began to rise, directors mixed erotic farces with gory horrors, saving the bloodiest of them for the closing part of the performances. Under the disguise of explicit and seemingly crude entertainment, playwrights and actors managed to address larger social issues and shared fears. Taboo topics made the core of The Grand Guignol’s sphere of expressive interests, making the theater both shocking and appealing to the crowd.

Playwright’s Paradise: The Writers Behind the Grand Guignol

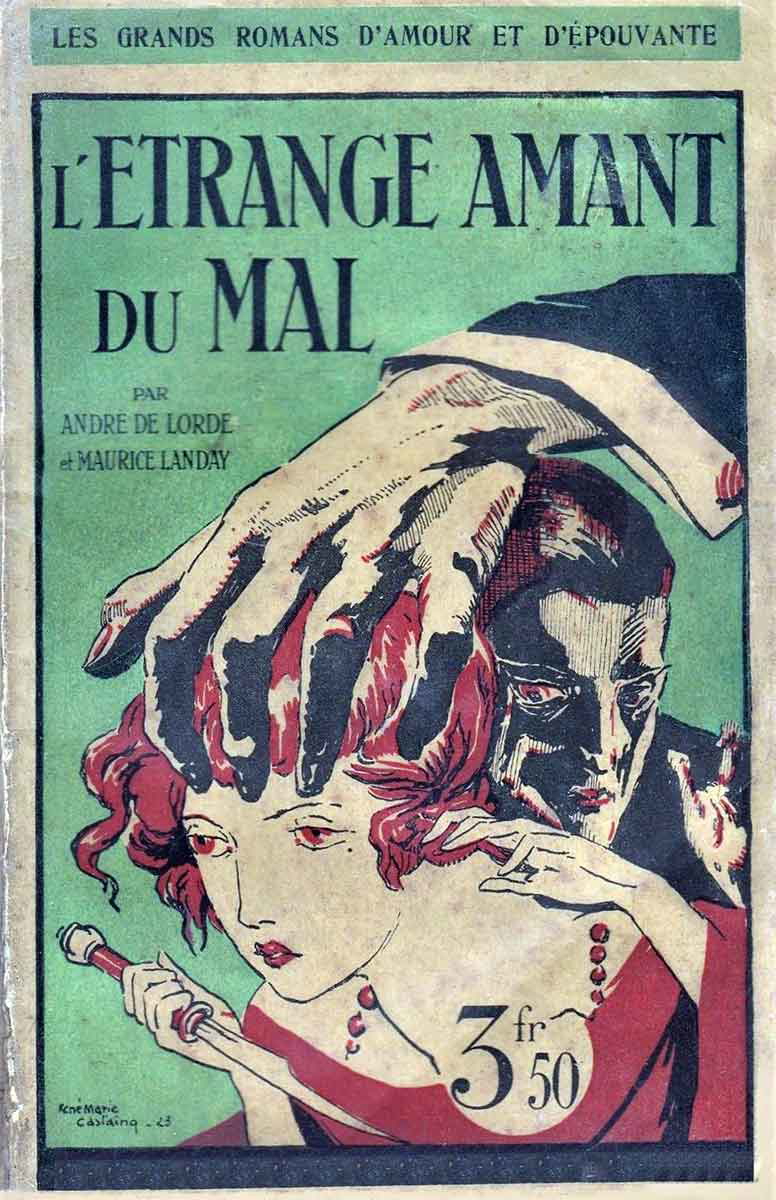

Over the decades of its existence, The Grand Guignol employed many writers, but not one of them was as successful and prominent as Andre de Lorde, who was known as The Prince of Terror. He seemed to be in equal parts the theater’s mastermind and its morbid creation. Noticing an unnerving obsession of the young boy with death, de Lorde’s father, a prominent doctor, attempted to cure it by taking his son to funerals and dissections. The effect, unsurprisingly, was quite the opposite and, by further traumatizing de Lorde, defined his future path.

Still, Andre de Lorde was far from a violence-obsessed maniac. He was a talented and intellectual writer with a perfect understanding of drama and suspense. People fainted during his shows not only because of the extremely naturalistic stage effects but also because of the palpable tension and the atmosphere of fear in the room.

De Lorde frequently collaborated with doctors and scientists to make his plays more realistic. The most prominent co-author of de Lorde was the psychologist Alfred Binet, famous for inventing the Binet Intelligence Test. Plays written by the duo were often considered the goriest and most unnerving in the Grand Guignol repertoire. Some of them expressed concerns about the contemporary state of psychiatric institutions and the incompetence of doctors leading to patients’ suffering.

We know that despite the widespread fame, not every project of the notorious theater was successful. In 1925, The Grand Guignol staged a play based on the novel The Pit by Russian Naturalist writer Aleksandr Kuprin. Kuprin was not a fan of The Grand Guignol but desperately needed money. The Pit was a scandalous novel that, a decade before, caused a stir in Russian-speaking circles for its overtly dramatic, hopeless, and explicit image of an average Moscow brothel. The characters, women forced into sex work, beaten and abused by brothel owners and their clients, desperately looked to either get out or to avenge their fate.

The stage adaptation of The Pit greatly annoyed Kuprin, as he believed that the exaggerated violence only mocked his characters. In Max Maurey’s version of The Pit, Zhenya, the sex worker who contracted syphilis, dramatically slit her own throat onstage, wheezing loudly. At the same time, in the original text, she hung herself in a bathroom while hiding from a brothel doctor.

Onstage Violence and Its Absence

In classical theater tradition, violence mostly happened off-stage, with some notable exceptions of outstandingly dramatic suicides or long-awaited acts of piercing the antagonist with a sword. The Grand Guignol, on the contrary, made grotesque open violence the central element of their story and its culmination. Exceptions to that rule were rare yet somehow even more blood-curdling than on-stage decapitations and blood transfusions. The play On The Telephone demonstrated no explicit violence on stage and barely any activity at all. The only character was a man sitting in a room and hearing his wife and children being murdered at the other end of the phone. The actor had no interaction with the audience and no dynamic action, thus making his performance even more unsettling and chilling.

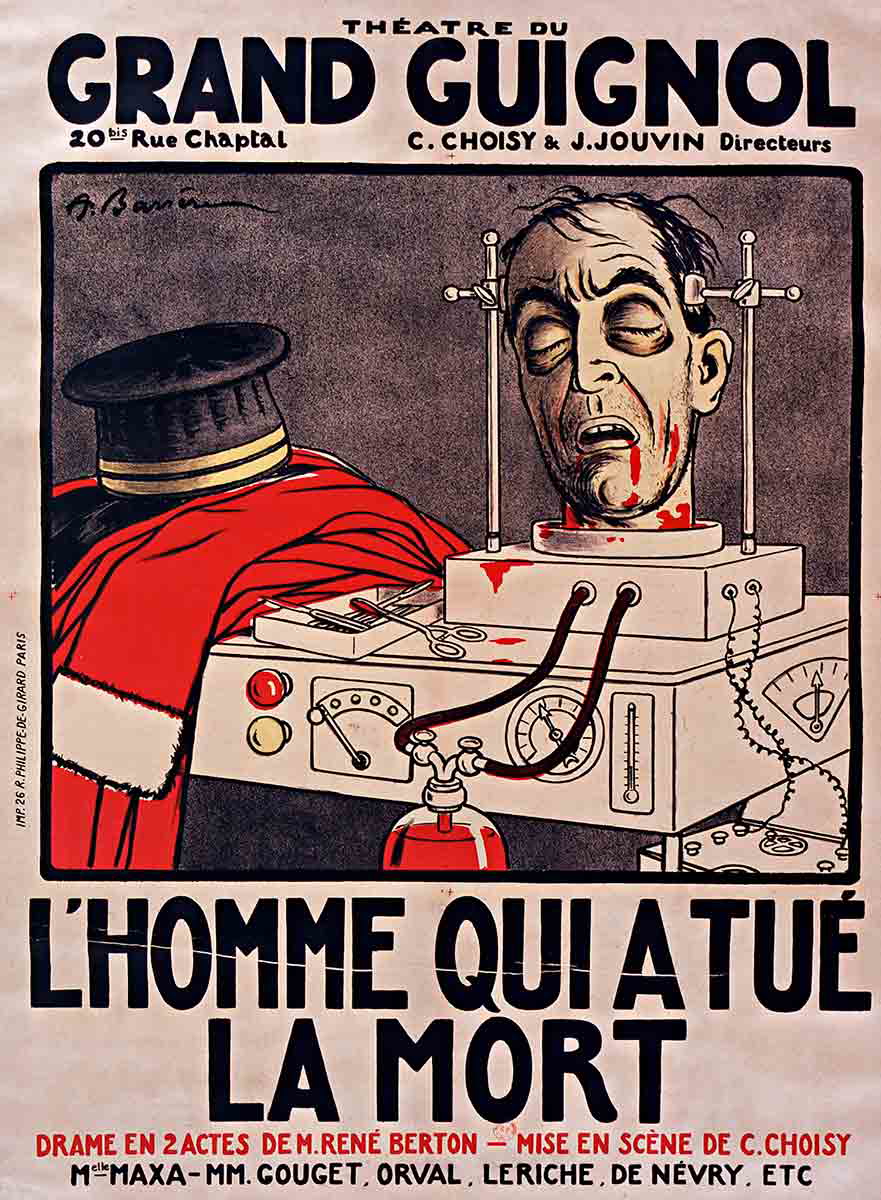

Technology and its abundance in modernity, in fact, enriched the horror vocabulary of The Grand Guignol. The play Horrible Experience explores the tragedy of a scientist whose daughter died in a car crash. Distraught by the loss, the father attempts to bring her back to life with modern machinery but ends up losing his life to the reanimated corpse. World War I also greatly contributed to the diversity of on-stage murder and torture. Poisonous gasses, experimental surgeries, and horrible mutilations were added to the theater’s repertoire.

A Crime at the Madhouse

One of the most popular and horrifying plays of The Grand Guignol, A Crime at A Madhouse, was co-written by Binet and de Lorde. A young girl, cured of her mental illness, is supposed to leave the asylum, but the nurse, a fanatical nun, refuses to let her go due to the girl’s supposed lack of faith in God. The girl is concerned about the threat posed to her by older patients, but the doctor dismisses her claims as symptoms of illness. At night, one of the patients, a one-eyed murderer, convinces others that a cuckoo bird hides behind the girl’s beautiful eyes and blinds her with a knitting needle.

The play, like many other writings by Binet and de Lorde, did not only focus on explicit and horrifying violence but reprimanded the way asylums and mental institutions functioned at the time. Filled with ignorant nuns and indifferent doctors, these institutions could neither help nor protect the patients, resulting in more violence.

The Last Torture

Many of the plays performed by The Grand Guignol exploited the legacy and practices of French colonialism in one way or another. Many pieces labeled as exotic described events on faraway lands under French colonial rule, sometimes loosely based on reality. The Last Torture had its origins in the 1899 Boxer Rebellion, a violent anti-colonialist uprising in North China.

On the surface, the play seemed to fall into the category of typical racist and imperialist pieces of writing of the time. Chinese rebels were never seen onstage or given a voice—the only evidence of their presence was violence. Over the course of the play, French sailors, nuns, and merchants suffered horrible mutilations and gruesome deaths from the unseen enemy. Still, many theater experts argue that The Last Torture was subversive in its grotesque violence. Although the bloodshed was indeed carried out by the Chinese, European colonialists were framed as the initial sources of it.

The Social Dimension of The Grand Guignol

The name of the theater itself contained a hint at the social significance of the Grand Guignol’s activities. Initially, Le Guignol was the name of a character of a popular puppet theater that aimed at adults rather than children, focusing on social issues and the burdens of the working class. Guignol, supposedly modeled after a Lyon silk worker, was kind but not too smart. Constantly taken advantage of by those in power, he usually managed to sort things out with his resilience and wit. Gradually, Guignol’s name became synonymous with puppet theater as a whole.

The Grand Guignol, despite its erotic and gory facade, essentially did the same thing as Guignol the puppet. In a shocking form of provocative plays, the theater company spoke of domestic violence and social inequality. Its exotic plots highlighted the horrors of colonial violence, and stories of mad scientists questioned the ethical limitations of medical experiments. For example, one of the most famous pieces, A Crime at the Madhouse, reflected upon the inhumane conditions inside mental institutions and the violence enabled, if not encouraged, by their incompetent administration.