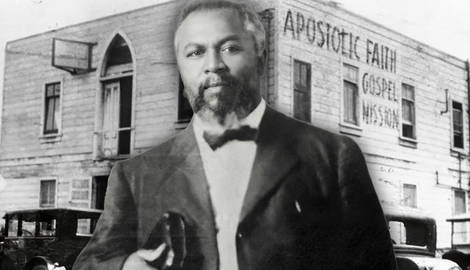

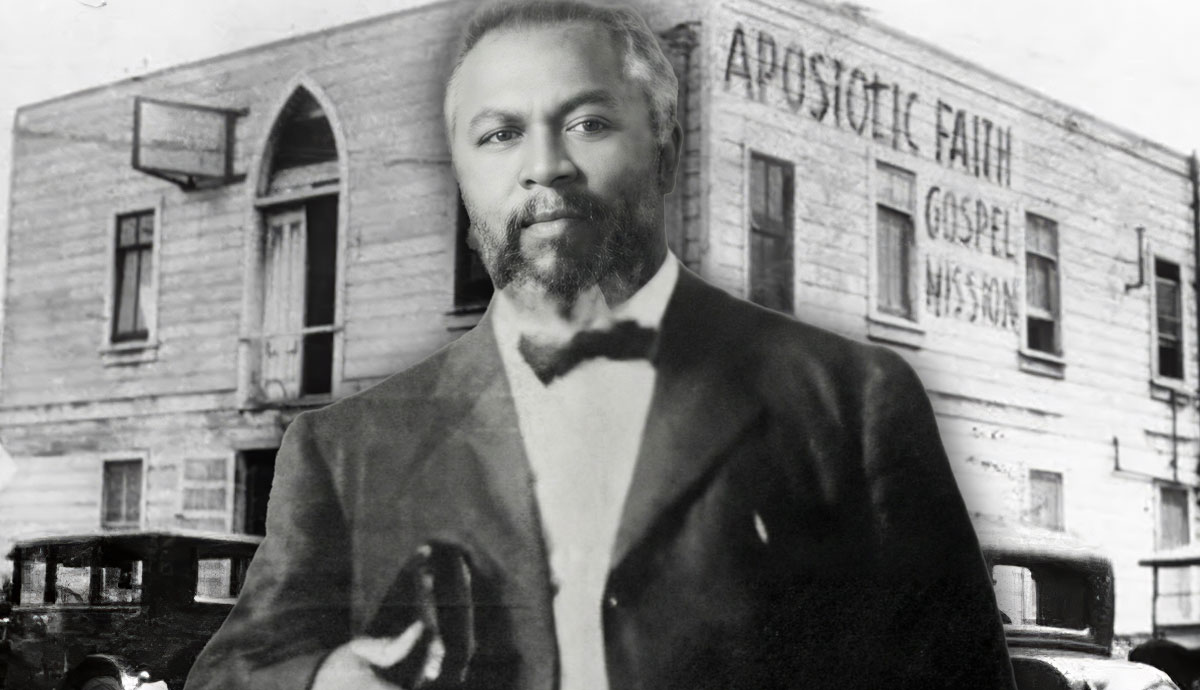

The catalyst that made Pentecostalism a worldwide phenomenon began with the preaching of a marginalized pastor named William J. Seymour in church-turned-stable on Azusa Street in Los Angeles, California. His driving idea was that the miracles of the New Testament could happen again.

William J. Seymour’s Post-War Context

The story of the Azusa Street Revival and, according to historical reckoning, world Pentecostalism, begins with a preacher named William J. Seymour. Born to formerly enslaved parents in Centerville, Louisiana in 1870, Seymour grew up in the troubled post-war era of the American South. The decade after the American Civil War is called “Reconstruction” by historians, since it was defined by efforts on the part of the federal government to rebuild the South as well as to ensure its compliance with the reality of Black citizenship.

The result was decidedly mixed, as many white citizens resisted the new order and sought, in a plethora of ways, to re-subjugate recently freed Black people to white status and interests. The most extreme of these measures were the frequent mob-killings of Black people called “lynchings,” of which Louisiana had one of the highest rates in the USA.

The Revival Occurred Just Before the “Great Migration”

White backlash to Reconstruction was one of several converging factors that led to the “Great Migration” of around six million Black people from former slave-holding states to cities in the north and western regions of the United States. This was also the beginning of a surge in Mexican immigration to the American southwest.

The number of Japanese people moving to Los Angeles was also increasing quickly at this time, and Chinese immigrants continued to arrive in California as well. The revival at Azusa Street took place at the beginning of this era of increasing diversity in Southern California. This would prove to be a crucial aspect of world Pentecostalism’s beginning, and would be part of what made William J. Seymour its central figure.

Charles Fox Parham Developed a Theology of Pentecostalism

While Seymour is rightly credited for bringing Pentecostalism to the world via Los Angeles, he was not the first to draw an essential connection between being filled with the Holy Spirit and speaking in tongues. This phenomenon had appeared at points throughout Christian history.

While growing up in Iowa, Charles F. Parham had experienced a miraculous healing of his legs as a teenager—an experience that led him to become a preacher later in life. As an adult, he grew dissatisfied with the Methodist form of religious practice in which he was ordained as a lay preacher and became involved in the “Holiness” movement that had lately begun to emerge out of traditional Methodism.

Parham began to travel the United States in search of a more miraculous spirituality. During his travels to various Bible colleges, he encountered people who spoke in tongues, and interpreted this as their having been endowed with a divine gift that allowed them to speak in literal, human languages that they had never learned.

Seymour’s Search Concurred with Parham’s

In 1900, Parham opened the Beth-el Bible School in Topeka, Kansas. But after facing opposition to some of his controversial ideas, he left this school only a year after its opening. Leading revival meetings along the way, he eventually ended up in Texas where, in 1905, he opened the Houston Bible School.

Meanwhile, however, William Seymour had been on his own journey of faith. A preacher himself, but with almost no opportunity for education in the South, Seymour had journeyed north as a young adult. Though raised a Baptist, he had an experience of conversion in a Methodist church in Indianapolis, Indiana. Both there and during a year of study at a Bible school in Cincinnati, Ohio, Seymour experienced a progressive form of the Christian gospel in racially integrated contexts. This would later become a key aspect of the Pentecostal movement.

Seymour Moved to Los Angeles

In 1905, Seymour met Charles Parham in Kansas while Seymour was pastoring a church there. Seymour became fascinated with Parham’s ideas about the filling of the Holy Spirit, and decided to go to Houston to study under him. Due to “Jim Crow” segregation laws, Seymour had to learn by sitting in the hall of Parham’s tiny Houston Bible School outside the classroom door.

Though the law prevented Parham from integrating his classes, Seymour soon realized that racism was also part of Parham’s theology. In particular, Parham held to a conspiracy theory called, “British Israelism,” which viewed British white people as the descendants of the ostensibly “lost” ten tribes of Israel. Seymour grew uncomfortable with this and other of Parham’s ideas and, though embracing fully Parham’s theology on the filling of the Holy Spirit, decided to leave Houston within two months of his arrival there. Seymour would later break more decisively with Parham and his brand of Pentecostalism, but only after inviting Parham to be a part of the Azusa Street Revival.

The Pentecostal Movement Begins

Accepting an invitation to pastor a Holiness church in Los Angeles, Seymour arrived there in February of 1906. His ministry at the church, however, was short-lived. Finding his teaching on the gift of tongues and the filling of the Holy Spirit foreign, he was quickly—and literally—barred from the church. Seymour, thus, found himself having to gather a small group of interested students in homes of patrons for prayer meetings.

But the meetings quickly grew. On April ninth, 1906, after Seymour had been in Los Angeles for less than two months, the first group of individuals received the “baptism” of the Holy Spirit and spoke in tongues. Seymour himself received the gift three days later. This became the marker of the beginning of the Azusa Street Revival. Soon the crowds of daily attendees had outgrown homes, and Seymour had to secure a local church building, which had lately been used as a horse barn and warehouse, to accommodate them.

Seymour Established the Apostolic Faith Mission

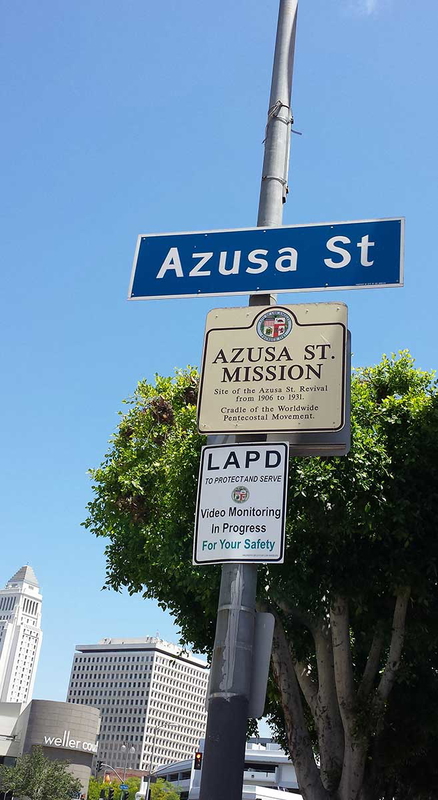

The building was the Stevens African Methodist Episcopal Church at 312 Azusa Street. It was renamed the Apostolic Faith Mission—known popularly as the Azusa Street Mission—and one of the most significant religions movements in modern history was born.

Beginning on the ninth of April, 1906, the Azusa Street Revival meetings occurred almost continuously—daily and often more than once daily—for three full years, after which they gradually grew less intense until they finally ended. The Apostolic Faith Mission, which from the beginning was not safe for large gatherings, was eventually torn down—a testament to the humbleness of this massive movement’s origins.

What Happened at the Revival Meetings?

Some of the members of the Pentecostal church with crutches and canes deposited in the church by those who have been healed by the church, Chicago, Illinois, by Russell Lee, April, 1941. Source: Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017788968/

Eyewitness reports suggest that the meetings were not characterized by noise or disarray. Rather, the environment was hushed and peaceful. Hymns were sung without instrumental accompaniment. The preaching was dogmatic. Seymour was passionate about what he considered to be sound doctrine, and would often address fine points of theological concern in his messages.

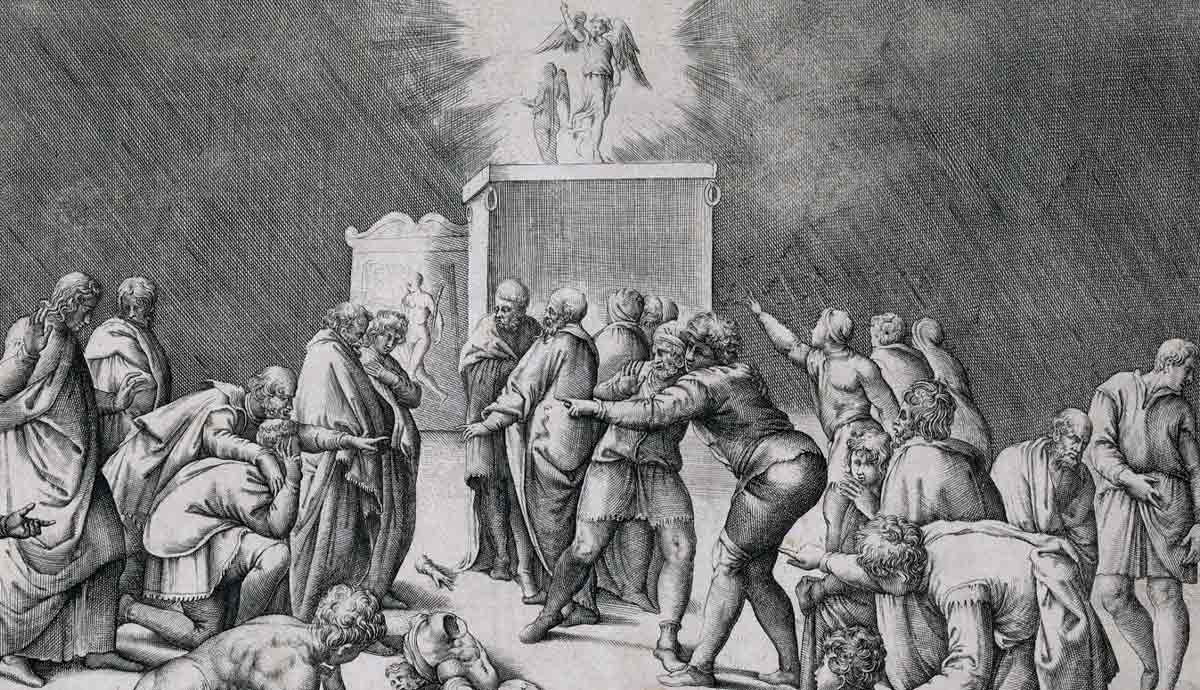

Reports of hundreds of healings emerged from the meetings, with claims that the walls of an upper room at the Faith Apostolic Mission was lined with the crutches that healed people had left behind. Exorcisms also became a familiar part of the meetings.

The Azusa Street meetings were of modest size, ranging from one hundred to fifteen hundred people. But the movement they spawned, and their influence on Christianity writ large, was enormous. Prominent church leaders from all over the United States came to witness the revivals for themselves, and many changed their view of spirituality and theology as a result of what they saw.

Finding the Roots of Pentecostalism

Looking back, Pentecostalism can be understood, metaphorically, as a tree. It has many branches, but they all come from the trunk, which is the Azusa Street Revival. But, what about its roots? While the sensational phenomena that define Pentecostalism may seem to have sprung up spontaneously, it emerged from deep historical roots. Quakerism, and the Holiness tradition that came out of Wesleyan Methodism are among these.

Pentecostalism’s emphasis on a personal experience of the divine ally it closely with Evangelicalism, with which it shares many of the same roots. William Seymour considered the revival he was leading to be in continuity with several eighteenth-century revivals in America, Europe, Australia, Asia, and Africa. Once word had gotten out of what was happening on Azusa street, the emerging Pentecostal movement spread around the world, most of the time through missionaries or local people who were already located in those places, far away from Los Angeles.

A Multiracial, Multiethnic Movement

The Azusa Street Revival occurred when racial segregation efforts were peaking in American culture. While the fantastical and miraculous phenomena that reportedly happened at the revival would eventually dominate the reputation of Pentecostalism, the truth is that American religion had experienced many such phenomena in previous revivals.

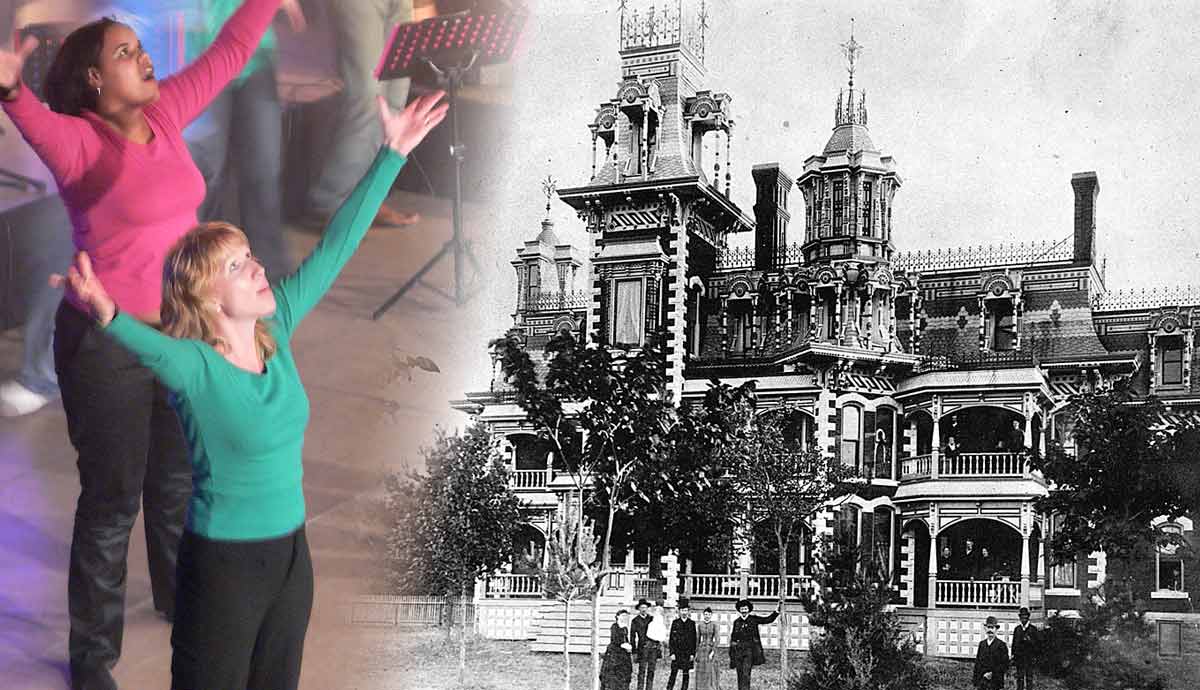

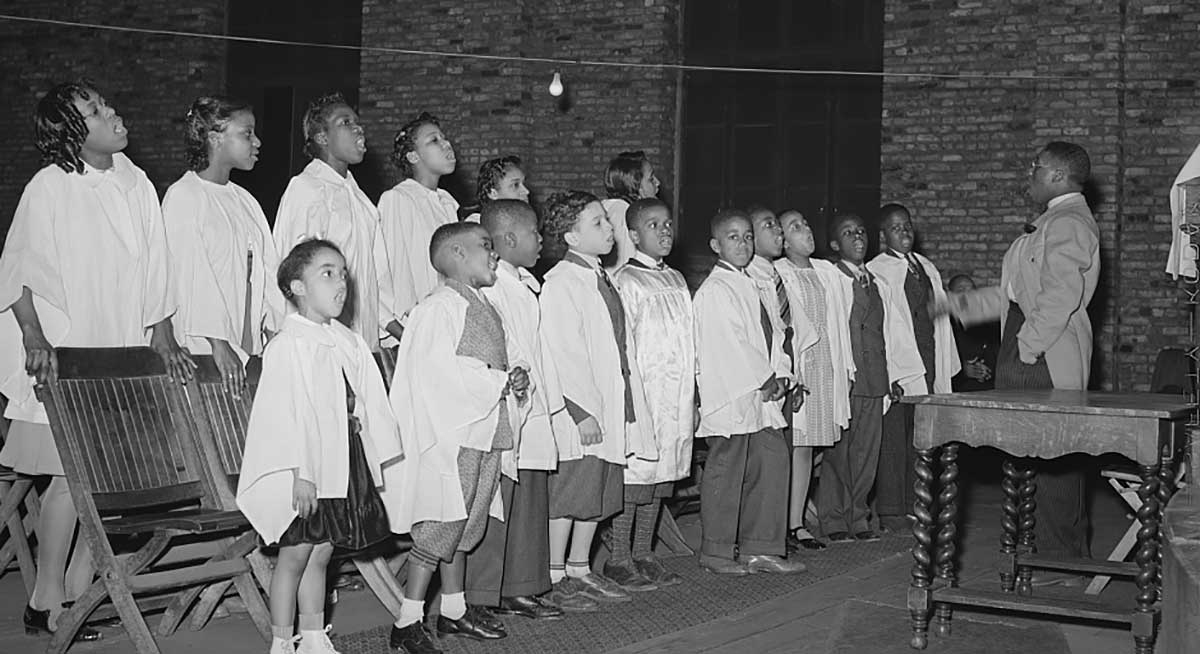

The real scandal that Seymour’s leadership caused was the audacious racial and social mixing that transpired at the Azusa Street Revival. Black, white American, Hispanic, Russian, Japanese, Chinese, and people of European ethnicities were not only mixing together in the same worship services—which was scandalous enough—they were also laying hands on one another’s shoulders for prayer, falling down on the floor side by side or into each other’s arms in spiritual ecstasy or during healings and exorcisms, and interacting in other ways deemed wholly inappropriate for a mixed-race gathering.

In addition, early Pentecostalism’s emphasis on the Holy Spirit’s equal gifting of men and women provoked further objections.

Criticism of the Revival’s Multiracialism Came from Inside and Outside of Early Pentecostalism

The initial objection to this racial mixing came from Charles Parham himself, who used racist language to condemn what he saw when he visited the revival in 1906. He continued to publish his attacks for years afterward. Parham’s central objections were theological, but they were always laced with racist ideology and rhetoric. Local newspapers were also roundly critical of the Azusa Street gatherings due, in great measure, to their interracial composition.

Seymour, however, believed that the movement’s multi-racial, interethnic character was essential to its biblical underpinning, since the “Pentecost” described in the New Testament was likewise overly interethnic. Theology aside, Seymour was certainly right: no movement has matched Pentecostalism in its ability to defy ethnic and racial barriers.