Before the Protestant Reformation flourished, mainly due to the printing press, several movements, both heretical and within orthodox belief, emerged in Christianity. One of these groups, the Waldensians, emerged in the 1100s and would have an impact on the Reformation a few hundred years later.

When the Waldensians Emerged

Sometime in the mid to late 1100s, a merchant from Lyon, France who went by the name Peter Waldo or Peter Valdez (it is unknown if his actual first name was “Peter”) gave away his property and wealth and began preaching the gospel. He espoused the value of poverty and sought to bring the gospel and the Word of God to the people so they could understand it.

Waldo would travel around the Lombardy region, which at the time was a breeding ground for other similar religious movements, many eventually declared heretical by the Roman Catholic authorities. Waldo was unique among these movements in that he was never an ordained priest or church leader.

Waldensian Beliefs

Waldensians generally held to the same core Trinitarian beliefs that were held by most catholics, as laid out in the Nicene or Athanasian Creeds. The most defining characteristic of Waldensians was their high value on personal poverty, sometimes to the extent that they considered it essential for proper Christian living.

The Waldensians differed from Catholicism in several ways. They spurned some of the beliefs which they saw as extra-Biblical, such as the use of relics and the ability of priests to forgive sins or withhold forgiveness. According to the anonymous poem written by a Waldensian in the 1100s called la nobla leyczon – “The Noble Lesson” –

“That all the Popes which have been from Silvester to this present,

And all Cardinals, Bishops, Abbots, and the like,

Have no power to absolve or pardon,

Any creature so much as one mortal sin;

‘Tis God alone who pardons, and no other.”

The Waldensians held to the concept that would become known in the Reformation as the priesthood of the believer – that all believers, in a sense, were priests that had direct access to God through Jesus Christ and could generally perform priestly duties. One other prominent belief held by the Waldensians is their rejection of infant baptism, particularly as the movement progressed.

Some views attributed to the Waldensians from both later Protestant supporters (such as viewing the Pope as the Antichrist) and Roman Catholic opponents (such as the Waldensians being non-Trinitarian) are suspect. Much of the Waldensian material that remains came either through sources appearing many years after the movement was founded, or through its harshest opponents.

What Did the Waldensians Accomplish?

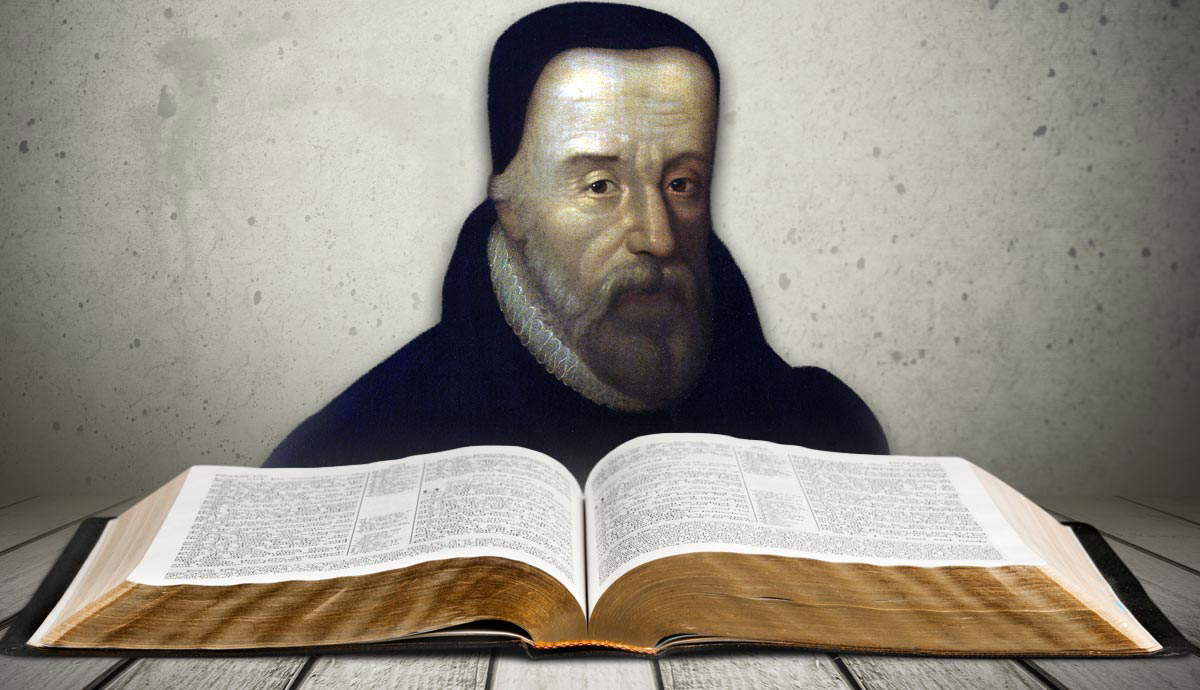

Probably the greatest accomplishment of Waldo was his production of the first New Testament into a common language. He commissioned a group of Lyon monks in 1170 to translate the New Testament from Latin into the Franco-Provencal language of the people to whom he preached. While the Roman Catholic leadership attempted to suppress his movement, the production of a vernacular Bible allowed the Waldensian movement to spread further into other parts of Europe. They also provided a sort of inspiration for the Reformation in later years, acknowledged by Martin Luther and even cooperated with John Calvin.

What Happened to the Waldensians?

In 1184 a formal excommunication from the Roman Catholic Church under Pope Lucius III was given to the Waldensians as well as various other heretical groups, such as the Cathars and Humiliati. Unlike many other groups deemed heretical, the Waldensians would survive as a movement despite several harsh persecutions, and would spread beyond Lyons into other areas, particularly Germany.

When the Reformation began in 1517, the Waldensians found kindred spirits and would be absorbed into the movement by 1532. However, their basis in France, which remained predominantly Catholic, ensured their continued persecution throughout the Reformation. The Waldensian Church persisted, and remains as an active congregation into modern times.