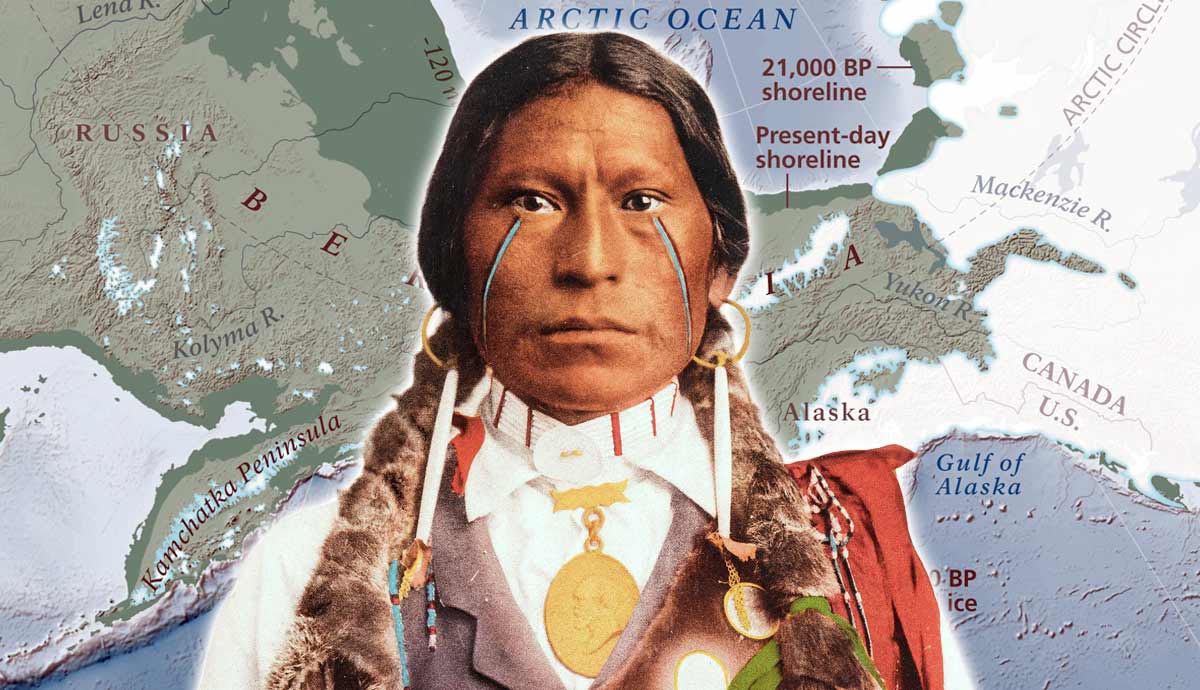

The Native American story began some 15,000-plus years ago. Using a now-submerged Arctic land bridge, they crossed from Siberia to Alaska. The land bridge, now known as Beringia, emerged during a period of low sea levels during the last Ice Age. Connecting North America and Asia, this 1,000-mile corridor existed as part of the tundra, with vast megafauna. Groups of hunter-gatherers crossed Beringia, following Ice Age herds like bison or mammoths. While some groups passed through, the current theory is that others settled in, remaining for generations. Beringia remained crossable between 30,000 and 12,000 years before disappearing under the ocean.

A Genetic Difference

A key similarity between Native Americans and Asian groups is genetics. The current theory is called the “Beringian Standstill Hypothesis.” This states that as groups slowly crossed Beringia, their isolation created genetic differences from their Asian ancestors. Some groups remained in place, possibly for as long as 10,000 years. The genetic difference would increase the further Native Americans traveled from Beringia. Yet, both Native Americans and northeast Asians traced their heritage to a common ancestor 25,000 years ago.

The Two-Route Theory

It is thought that “Paleo-Americans” used two routes to roam deeper into America. This migration occurred in multiple waves over centuries.

- Ice Free Corridor: Hunter-gatherer groups migrated between two great ice sheets. They spread through central Canada, next moving south along the Rocky Mountains. The later Clovis culture may have emerged from this movement. Archaeologists date the first Clovis sites back to nearly 13,000 years.

- Coastal Migration: These seafaring people sailed south, moving south to points in South America. Archaeological evidence and local people’s oral histories confirm this route. A prime example is Triquet Island (British Columbia), dated to around 13,600 to 14,100 years ago.

Evolving from Travelers to Cultures

As the founding groups settled across the Americas, they adapted to local environments around 13,000 years ago. The wanderers became semi-nomadic or established permanent patterns. The first to emerge (though debated) was the Clovis Culture. Known for its game-changing spearhead, this spearhead enabled hunters to tackle bigger megafauna species. Knowledge of this spread across North America and south to even Venezuela, either in settlements or stuck in animal skeletons.

The Clovis Culture gradually evolved into more local traditions, such as Folsom and Dalton (roughly 10,000 years ago). They came after the megafauna’s extinction. For example, improving the Clovis spear point meant better hunting for smaller species. Necessity led to creativity, so tools like microtools and scrapers were created. Regional differences crept in as the Paleo Americans adjusted to local situations. Smaller groups used better hunting strategies. Examples include kill sites and tool caches, representing a more sophisticated society.

By 8000 BCE, the Ice Age stood only as an ancestral memory. During this Archaic Period, native societies became complex. Broader foraging meant hunting, though still important, mixed in with resources like wild plants and fishing. Trade began between groups and settlements, like the oval-shaped complex Watson Brake in Louisiana.

Continuation and Development

The centuries between 2000 BCE and 1000 CE witnessed faster advancement. As complex societies formed, they created or increased distant trading contacts. Some spanned hundreds of miles, like the Hopewell tradition (200BCE to 500 CE). This far-flung network of tribes connected groups from Canada to the Gulf Coast. Besides usual trade goods, exotic items like copper from the Great Lakes to Gulf Coast shells changed hands.

Cahokia, part of the Mississippian Culture, emerged circa 1050 CE-1350 CE. Cahokia is considered a true city, particularly in terms of architecture, politics, and social hierarchy. It was the largest city of its time in North America.

A Linguistic Heritage

As mentioned, migration across Beringia came in waves in either direction. That said, Native languages developed into families and others with no correlation (Haida). Specific languages still show connections to Siberia. One family, the Na-Dene, shows that Navajo and Apache have kinship with the Siberian Yett languages.

Today, in North America, there are three hundred languages. More than a few are extinct or slowly being revived. These fall under thirty or so language families. If all of the Americas are included, the count reaches over 900 indigenous languages.

Oral Traditions as History

Though usually non-linear, oral histories can confirm Native American origins. These show origin stories, lineages, and ancestry. They show routes, sacred sites, or changes like the Ice Age in their past. Actual confirmation has been made several times. Alaska’s Tlingit tribe used oral tradition to show archaeologists where a 500-year-old village sat, confirming their predecessors’ story. The Native American origin story encompasses scientific, cultural, and spiritual traditions, and we now have a solid understanding of this rich past. However, it shouldn’t be written in stone, as the whole picture is not yet fully known.