The story of the horned Moses can be approached from several angles. Due to horns’ medieval association with the Devil, depictions of a horned Moses may betray a troubling antisemitic bias. But, originally, the bizarre image stemmed from an odd translation choice made by one of Christian history’s greatest scholars.

Jerome’s Vision for a Latin Translation of the Bible

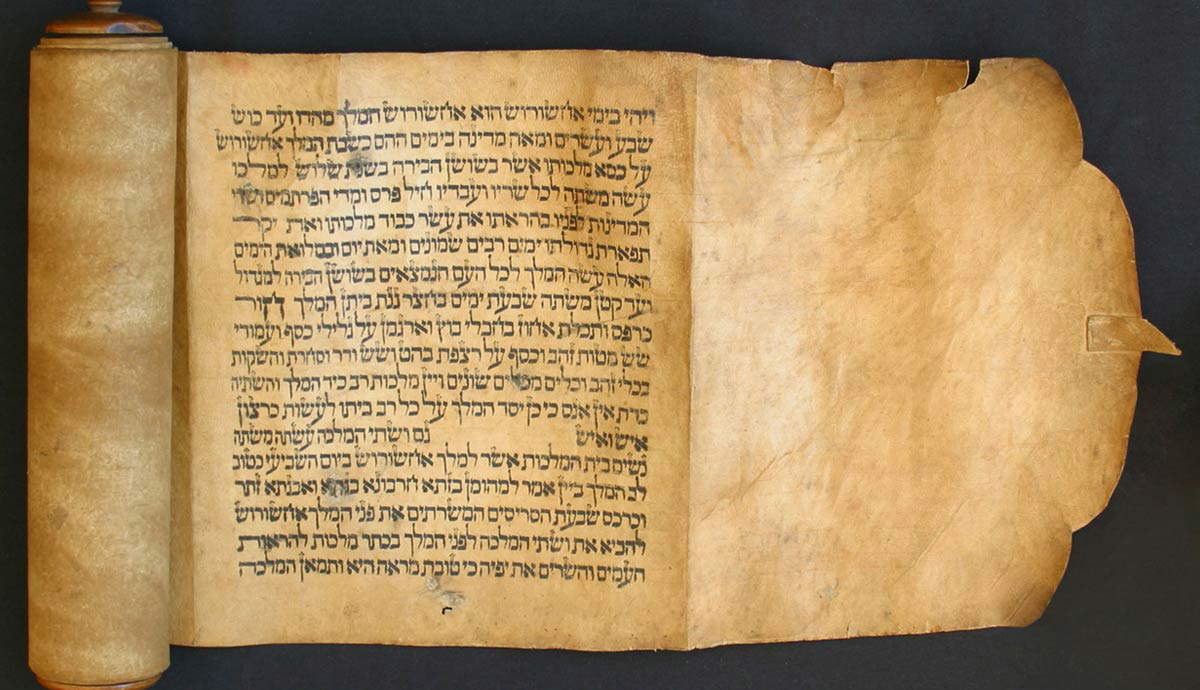

While the vast majority of Christians in his day used the Old Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible as their primary Old Testament text, a Christian scholar named Jerome became convinced that, not only should the Bible be translated from Hebrew as its original language, it should also be made available in the public language of the West. Having been commissioned by Pope Damascus I to work on the Latin translation of the New Testament, he also began creating a Latin translation of the Hebrew Bible in the late fourth century. Eventually, the entire Hebrew Bible was made available in Latin.

The impact of Jerome’s work was beyond significant for Western Christianity. Not only did Western Christians come to see the Hebrew Bible rather than the Old Greek version as its standard text, Jerome’s Latin Bible gradually became so popular in the West that, eventually (in the sixteenth century), it was made the official Bible of the Roman Catholic Church. It is known today as the Latin Vulgate translation.

Written Hebrew Does Not Necessarily Include Vowels

Hebrew words are typically built from three-consonant “roots.” While more consonants must be added to form certain conjugations of verbs, in the case of the most common form of verbs conjugated in the third-person singular, usually all that can be seen of the written word is three consonants. Similarly, when it comes to singular nouns, many Hebrew words appear as three juxtaposed consonants. And yet, the vowels can be crucial for understanding the meanings of words.

Of course, this goes without saying, since vowels make a difference in any language! But in Hebrew, as in other Semitic languages, there is a catch: the vowels are not necessarily written. Sometimes, vowels are indicated by a precise pointing system that uses dots and dashes above and below the Hebrew consonants. But these are not necessary for speakers of the language, since, due to a lifetime of speaking the language, they know intuitively where the vowels should be even without these vowel marks.

Jerome Decided to Translate k-r-n as a Noun Instead of as a Verb

Because of the ambiguity regarding where vowels are placed in Hebrew, something strange happened while Jerome was translating Exodus thirty-four from Hebrew to Latin. This chapter tells the story of when Moses received the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai. As Moses descended from the mountain, the Hebrew text of verse twenty-nine says that his face “shone,” from the Hebrew root k-r-n, with light.

But, the relatively rare, three-consonant root of the Hebrew verb for “to shine”—k-r-n—is the same as the Hebrew root for the noun meaning “horn.”

An Anatolian Greek scholar and convert to Judaism named Aquila who had lived three centuries before Jerome had chosen “horn” when translating this Hebrew word. In the absence of certainty about what vowels should be pronounced, and perhaps following Aquila’s lead, Jerome chose to translate k-r-n “horn” instead of “shone.” And thus, Moses, having encountered God’s glory, had grown horns.

Horns Are a Symbol of Exaltation and Authority in the Bible

In western contexts, horns eventually became associated with the Devil. But the Bible never associates horns directly with the demonic. Instead, horns are symbols of power and authority, whether it is wielded by good or evil, in Scripture. The corners of the altar in the Israelite Tabernacle and Temple were adorned with horns, and the animals sacrificed thereon were usually males from species that grow horns.

In biblical poetry, the exaltation of a person or groups “horn” signifies their victory or success. Horned celestial creatures—monsters, actually—who appear in biblical apocalyptic texts tend to represent powerful rulers. These often have more than just one pair of horns. Thus, the themes of brilliance, exaltation, glory, and the horns of an animal are actually symbolically related in the Bible. These associations may make Jerome’s (mis)translation of the Hebrew root k-r-n even more understandable.

The Horned Moses May Have Played a Role in the History of Anti-Semitism

However, by the Medieval Era, horns had become widely associated with demonic imagery in Europe. Unfortunately, there is some evidence that the horned Moses in art was not always merely the benign result of an innocent mistranslation; it may have carried with it anti-Semitic overtones.

Moses was not depicted with horns in art until about six hundred years after Jerome first created his translation, and a horned Moses would not begin to appear commonly for several more centuries after that. This means that the slow emergence of the horned Moses correlated with the gradual association of horned mythical creatures (like Pan, fauns, satyrs, etc.) into the demonic. In turn, horns were becoming a staple of imagery depicting the Devil and his minions. European antisemitism, and the visual stereotypes that fuel it, was also becoming widespread and increasingly vicious during this time.

Some historians argue that, in at least some cases, the horned Moses was too readily associated with demonic creatures who were also increasingly being depicted as horned, and that this may have fueled antisemitism. While difficult to prove a causal relationship, the antisemitic bias ubiquitous in Europe by the sixteenth century may have an echo is some artistic renderings of the Jews’ most celebrated prophet.

Some Depictions of Moses Combine Light and Horns

Perhaps in order to keep the horned Moses tradition while also seeking to gently set aside its ridiculousness, many post-medieval depictions of the biblical hero show Moses with two beams of light shining from his head. They are horn-like, yet composed of light particles rather than keratin. These horn-like light beams evoke the halos of angels rather than the headgear of earthly beasts.