Few kings in English—or indeed global—history have transformed a country to such an extent as William the Conqueror did when he landed on England’s shores in 1066. The year is still etched into the minds of English people to this day, from schoolchildren to keen historians. But just how was William perceived after the invasion, when he took the Crown of England from the Saxon king, Harold II, following his defeat at the Battle of Hastings? Find out in this article.

Before the Conquest

William the Conqueror was only a name given to the man who was actually William, Duke of Normandy, following his invasion of England in 1066. Born around 1028 in Falaise, Normandy, William was actually a bastard (and he would also come to be known as William the Bastard in his later life), which makes his rise to power even more astonishing given the age that he lived in.

His father was Robert I, Duke of Normandy, and William was born to him and his mistress, a woman known as Herleva. Despite his origins, he eventually managed to claim his father’s dukedom of Normandy by 1047, but he did not fully gain control of it until around 1060 due to the sheer amount of controversy it caused.

However, his marriage to the formidable Matilda of Flanders in 1051 provided him with an important ally in the neighbouring territory of Flanders, and with this newfound power, he was able to secure more local territory, incorporating the county of Maine into his dukedom by 1062.

Did William Have a Legitimate Claim to the Throne?

This is perhaps the biggest question on readers’ minds, so we will address it early on. The simple answer is yes—and this is how.

The English king who William was related to (albeit distantly) was Edward the Confessor—he was William’s first cousin once removed. Edward was childless, and William thus held a rightful claim to the throne. However, while on his deathbed in January 1066, Edward allegedly named the powerful English earl Harold Godwinson as his heir.

William argued that Edward had previously promised the throne to him and that Harold had sworn to support his claim. William was naturally angered when Harold took the English crown for himself.

William responded by building a large fleet and preparing to invade England to take what (in his mind) was rightfully his.

The Battle of Hastings and the Immediate Aftermath

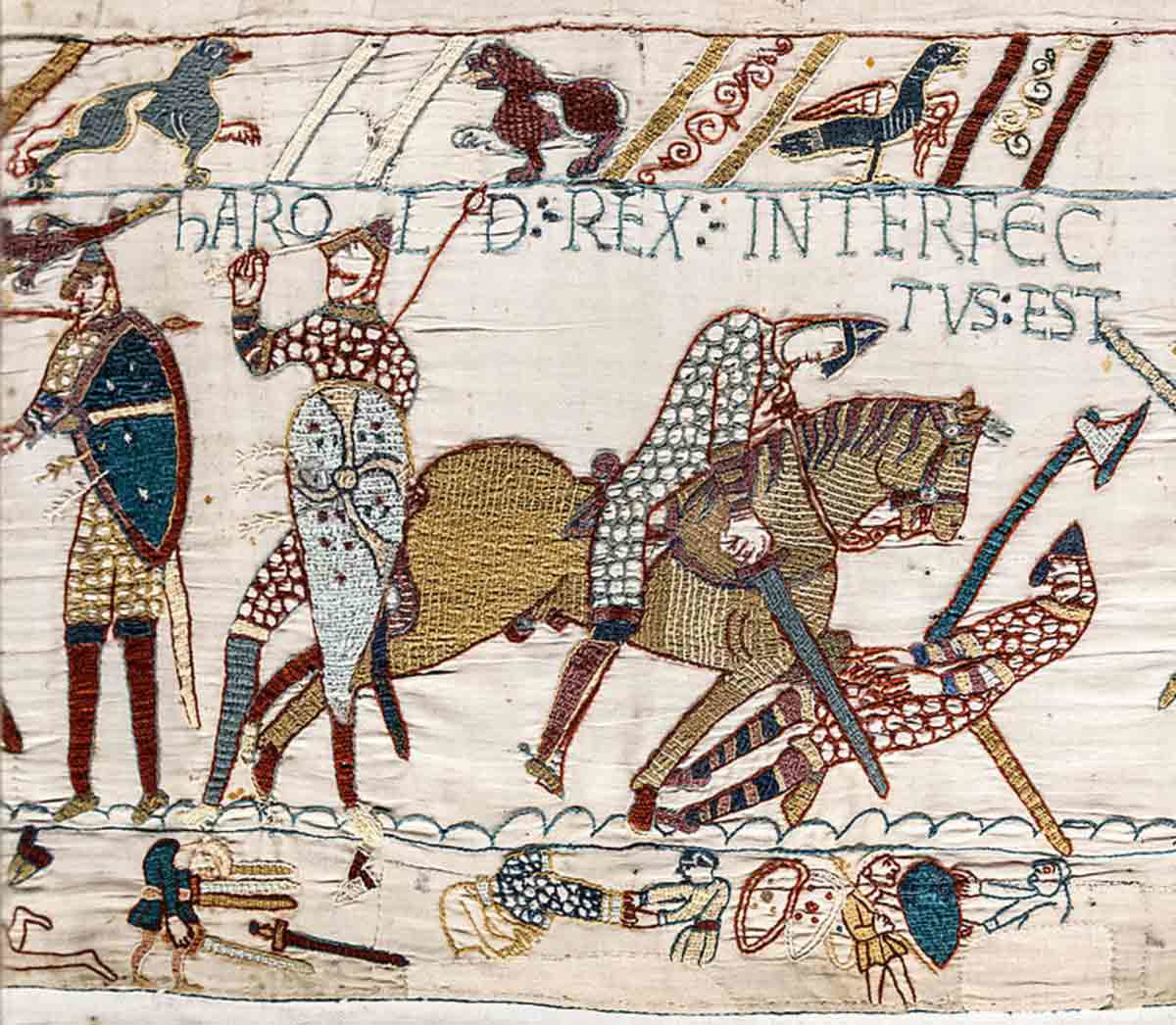

William set sail for England in September 1066 and decisively defeated the English king, Harold II, at the Battle of Hastings on the south coast of England on October 14 the same year.

After the battle, William made his way to London, and he was crowned on Christmas Day 1066 at Westminster Abbey, thus becoming King William I of England. For some contemporaries, this was the beginning of the end—the French had invaded England! For others, it was a fresh page in the already culturally diverse history of England.

William knew that he had to return to Normandy to solidify his rule there, so he made the conscious decision to leave two of his most trusted men in charge of England. One was Odo, his half-brother (who was also the Bishop of Bayeaux), alongside William FitzOsbern, who was the son of his former guardian.

William headed back to Normandy, trusting many of the former English sheriffs to remain in charge of their original posts while England was under the guardianship of Odo and FitzOsbern.

Of course, it did not take long for trouble to arise, particularly in Saxon strongholds, and especially for those who remained loyal to the late King Harold.

The Early Rebellions

Northern England has long been known as a hotspot of rebellion. Recent examples include the Miners’ Strikes in the 1970s and 1980s in reaction to Margaret Thatcher’s government and the Jarrow March in the 1930s. Further back, it was the Houses of York and Lancaster that vied for power in the 15th century, but even long before that was one of the most important events that pitted the north against the ruling class.

One of the most famous events in William’s reign would become known as the Harrying of the North—a systematic oppression of the northerners in his kingdom who rebelled against him.

In 1068, two of the leading rebels in England, Edwin, Earl of Mercia, and his younger brother, Morcar, had had enough of William’s oppressive rule. They revolted against him with the support of Gospatric, Earl of Northumbria.

The king got wind of his rebellion and marched through Edwin’s lands, constructing Warwick Castle on the way. It did not take long for both Edwin and Morcar to succumb to the king’s power, but William was far from done.

William built York Castle and Nottingham Castle as symbols of his strength and power, as well as the castles of Lincoln, Cambridge, and Huntingdon, placing fervent supporters of his cause in each to discourage local uprisings.

The Harrying of the North Continued

In 1069, Edgar Ætheling, a great-grandson of King Æthelred II and, therefore, a valid claimant to the English throne, rose up against William.

Edgar attacked York, and while William returned and built a second castle, Edgar still remained free and instead opted to join up with King Sweyn II of Denmark, who had sent fleets to attack the Yorkshire coast, as well as Shrewsbury and Exeter.

Together, Edgar and Sweyn took York, and Edgar was proclaimed king by his supporters. William headed north and symbolically entered York on Christmas Day 1069, wearing his crown to show who the real king was.

William then paid off the Danes, while Edgar fled to Scotland. Just like before, William was not finished with the rebellious north. As a demonstration of his power and ruthlessness, he marched north to the River Tees, ravaging and burning the countryside where he went so that the northerners would struggle to cultivate the land and grow crops.

William then turned west, marched across the Pennines, and built the castles of Shrewsbury and Chester. This episode in William’s reign was all but over by April 1070.

The Revolt of the Earls

It was not just the common people that William had to deal with when it came to revolts and rebellions. In the 11th century, governing one dukedom was difficult enough—let alone governing a dukedom and a newly-conquered kingdom. William had to manage wars and trouble on two fronts. The next major revolt in England was the Revolt of the Earls in 1075.

Interestingly, the exact reason for the Revolt of the Earls is unclear. What we do know is that it happened at the wedding of Ralph de Gael, the Earl of Norfolk. Waltheof, the Earl of Northumbria—despite being one of William’s favorites—was also involved.

However, William’s most fervent supporters, including Odo, proved their worth to him by preventing the rebellion from spreading. Ralph was trapped in Norwich Castle by Odo, before leaving it under the control of his wife and escaping to Brittany, where he attempted to continue the revolt, to little avail.

William returned to England to celebrate Christmas at Winchester in 1075 and dealt with the aftermath of the rebellion, executing Waltheof in May 1076.

William at Home

Naturally, to be a successful medieval king, one had to be a savvy military tactician—and this was no different in William’s era.

As has previously been mentioned, he made a huge effort to establish his military dominance but also to increase the security of England during his reign, building castles—the ruins of many of which are still standing almost 1,000 years later.

William is also credited with building the White Tower—the famous keep at the Tower of London, which is still visible and can be visited today, in the heart of the English capital.

William is also credited with taking acres and acres of land—approximately 36 parishes’ worth—to establish the New Forest as a ground for hunting, one of his favorite sports. The forest still stands today and is a refuge for much of Britain’s native wildlife.

The Administration of the New Kingdom

But just how did William the Conqueror manage to rule this brand new kingdom, with its unusual language and customs?

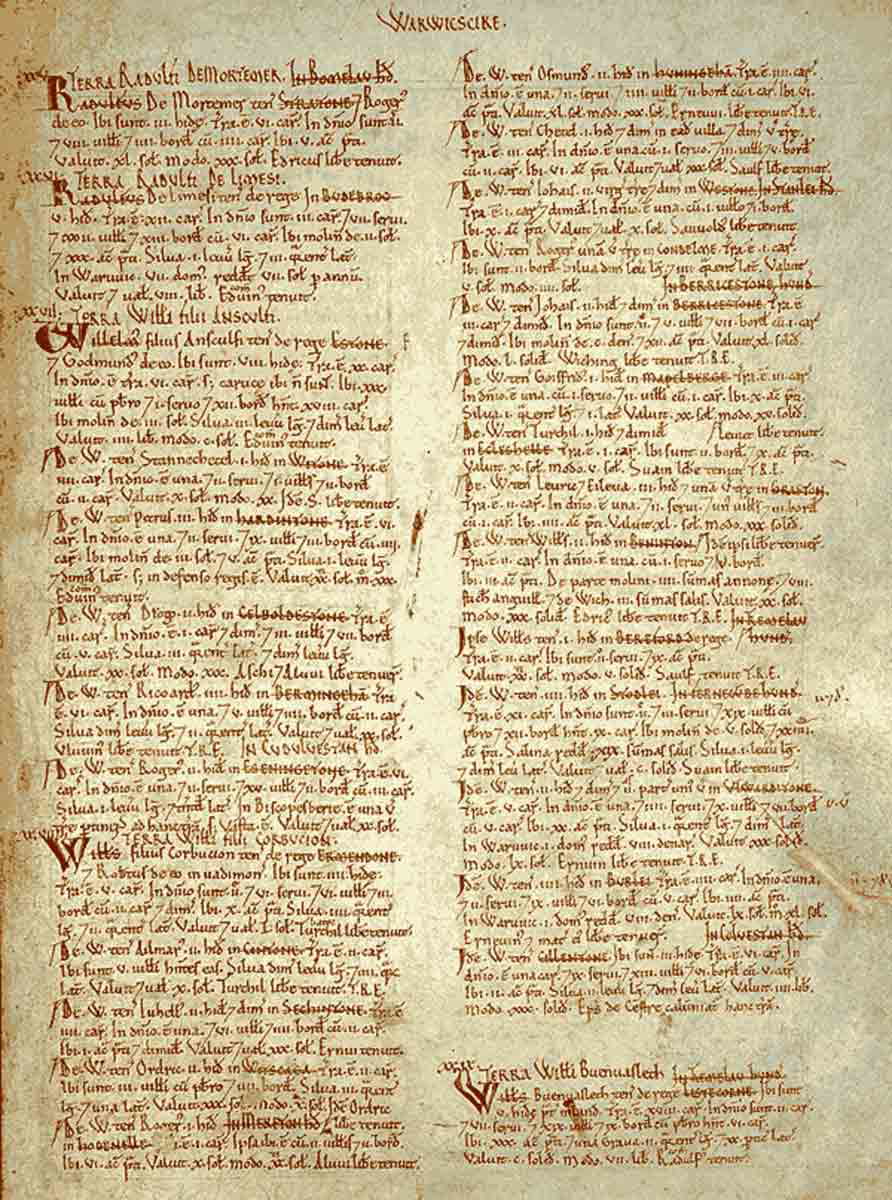

Perhaps the most famous example is the Domesday Book, which was ordered at Christmas in 1085 and completed around August 1086.

The Domesday Book was a great survey of the kingdom, listing the different towns, parishes, cities, and landholdings so that the king could gather an idea of how to tax the kingdom appropriately and rule it generally. Almost all towns, parishes, and villages south of the River Tees were listed, and it is one of the most important primary sources for the Medieval Era for historians.

William’s Death and Legacy

Naturally, there would be controversy as soon as William died—should his (currently warring) sons rule Normandy or England?

The crown of England was passed to his second-eldest son, who would go on to rule as King William II of England, and another of his sons, Henry, would succeed his brother as king and reign for an incredible 35 years as King Henry I of England.

This fully established not just William’s legacy but the legacy of the Norman conquerors—England would be ruled by Normans and descendants of Normans for hundreds of years.

As for William’s legacy and reputation, he is still clouded in controversy. Some see him solely as a conqueror, the greedy Norman duke who stretched too far and took more than he needed.

Others, however, have a more nuanced view—William was a strong leader who knew when to step back and let others work for him, as was seen with his fervent supporters helping him to suppress the Earl’s Revolt in 1075.

William was also ahead of his time in terms of administration: the Domesday Book of 1086, compiled a year before his death, still remains one of the most important primary sources for the medieval world that we have access to today.

Overall, William the Conqueror, King William I of England, was perceived as a strong but ruthless leader at the time, and still is to this day—a ruler who firmly established how England would be governed for the centuries to come.