William Hogarth was one of the most popular British artists who created works that were understandable to all classes and groups of his contemporaries. Hogarth was famous for his satirical lessons in the form of popular engravings, but some sources suggest he was not as morally pure as he appeared to be. Read on to decode William Hogart’s work and understand the lessons he taught his audience in the 18th century.

The Groundbreaking Career of William Hogarth

William Hogarth had a remarkable life and a surprising career path. Born into a poor family with a father who was a teacher with eccentric business ideas (such as opening a cafe where everyone spoke only Latin), Hogarth spent his childhood looking for ways to feed his mother and siblings, as his father was confined in a debtors’ prison. One of the occupations available to him was commercial engraving. While working, he constantly trained and studied fine arts to become an illustrator. Gradually, his skill and dedication made him popular amongst affluent clients. Still, his most famous works were the reprints of his satirical series on human vices, teaching moral lessons to his contemporaries.

Hogarth usually painted his series before making etchings based on them. Prints of Hogarth’s stories were immensely popular across Europe and even became the basis of artistic knowledge for some famous artists. For instance, the mother of James McNeill Whistler, a strict and conservative Christian, gave her son books with Hogarth’s prints while he was ill. Thus, these images became Whistler’s first encounter with art and propelled his further interest.

Hogarth was rather fond of self-portraits, so we know enough about both his physical appearance and the way he wanted to be seen in society. Sometimes, he painted himself in powdered wigs and formal attire, indicating his status as a gentleman, but sometimes he preferred a more romantic image. In his most famous self-portrait, he depicted himself wearing a Westernized version of a kimono, adding an exotic flair to his image, with his pet pug beside him. If you cannot recognize a pug in the image, it is mostly because the breed has transformed over the past two centuries due to both changing breeding trends and genetic mutations that seriously compromised dogs’ health.

A Harlot’s Progress: Hogarth’s Take on Sex Work

One of the most famous series of moralizing engravings created by William Hogarth was the set of six images showing the path of the main character, Moll Hackabout, from a naive country girl to an ill and destitute sex worker. Looking for work in service, Moll is taken advantage of and forced to work as a prostitute. Soon, she receives a prison sentence, falls ill, and dies, leaving behind her illegitimate young son.

Hogarth was the master of little details that made his images more complex than they seemed at first glance. Most of these details would mean nothing to a present-day viewer but were clear to Hogarth’s contemporaries. For instance, as the story of the unfortunate sex worker progressed, Hogarth’s heroine started to wear faux beauty marks glued to her face. Apart from judging her excessive vanity and obsession with recent fashions, Hogarth also hints at the possible venereal diseases she might have contracted during her work. In the 18th century, sex workers often used fake beauty marks to cover the early signs of syphilis. In the scene where the heroine distracts her wealthy patron so that her lover can escape, the mole plastered on her forehead indicates her corruption, both moral and physical.

A Rake’s Progress: Cautionary Tale for Young Men

Another immensely popular series warned British young men from recklessly spending their fortunes on gambling and women. A Rake’s Progress, told in eight images, presents another set of fictional characters—Tom Rakewell, an heir to a rich merchant, and his pregnant lover Sarah, whom he promises to marry with no intention of keeping his promise. Rakewell spends all his fortune on gambling, horse races, and orgies, gets robbed by sex workers, thrown in prison for accumulating debts, and ends up in the infamous Bethlem Hospital for the insane.

All this time, Sarah, at first pregnant and then with her illegitimate child in her arms, tries to save her lover from his fate, paying his debts and comforting him. Still, Rakewell rejects her help, turning into another Bethlem resident visited by wealthy ladies for the thrill of seeing a madman.

Hogarth used the painted versions of this cautionary series as advertising to attract buyers and typographies who wanted to print copies of them in the form of engravings. Due to the printing process, these images were typically reversed, with some details omitted or altered.

Marriage A La Mode

A less popular series by Hogarth titled Marriage A La Mode (meaning “fashionable marriage”) focused on arranged marriages and their detrimental consequences for everyone involved. The plot was as simple as it was typical for Hogarth’s time: an heir to an aristocratic family who lost all their wealth plans to marry the daughter of a nouveau riche merchant to retain familial prestige and wealth. The first image of the series depicts the prospective spouses signing a marriage contract.

Despite the seeming seriousness of the matter, no one is actually interested in their future partner. The bride shamelessly flirts with a lawyer while the groom is too busy observing his own reflection in a nearby mirror. The marriage quickly turns to disaster as the couple is clearly uninterested in each other while enjoying affairs on the side. A small dog finds a lacy lady’s cap in the husband’s pocket, once again indicating his infidelity.

Gradually, the unfortunate family collapses as the husband, ill with syphilis, challenges his wife’s lover to a duel and gets killed. The lover is executed, and the now-widow dies by suicide. Even the new generation of the family has no future in Hogarth’s mind: the couple’s little daughter, shown on the last plate, has dark spots on her face, indicating hereditary syphilis that she inherited from her father. Unlike Hogart’s other moralist series, Marriage A La Mode has a much more compassionate tone. The characters are the victims of a situation they never chose and have no way out of the unfortunate union.

Hogarth’s Fight With Bad Habits: One Portrait at a Time

Apart from designing visual moral lessons for a wider public, Hogarth also worked on commissions exposing his clients’ vices and praising their virtues upon consent. Among the most famous images of that kind was the not-so-flattering portrait of Francis Matthew Schutz, the cousin of Prince of Wales and notorious partygoer. Annoyed with Schutz’s drinking habits and excessive interest in women, his wife commissioned a portrait from Hogarth, showing her husband vomiting into a chamber pot after a rough night.

The artist spared no detail, showing the model obviously suffering from a merciless headache. Above the bed, he painted a lyre with an inscription from Horace expressing the character’s past love for women that he had to quit, metaphorically hanging his lyre to rest. Some historians believe the inscription was a call for Schutz to mind his manners as a married man. Others are less favorable, suggesting that years of drinking have affected Schutz’s intimate health beyond repair.

It is unclear if the image had fulfilled its goal of curbing Schutz’s vices, but it surely made his heir uncomfortable enough. At some point in the painting’s history, it was retouched, with the pot painted over with an image of newspaper. Francis Schutz was then seen reading in his bed, curled in a weird position and reading intently. The only thing hinting at the original purpose of the work was the inscription on the back of the canvas, informing the viewer of Mrs. Schutz’s commission and her dedication to reforming her husband. Only after cleaning the image from traces of later involvement was the true purpose and meaning of the work revealed.

William Hogarth and the Hellfire Club: Was He a Hypocrite?

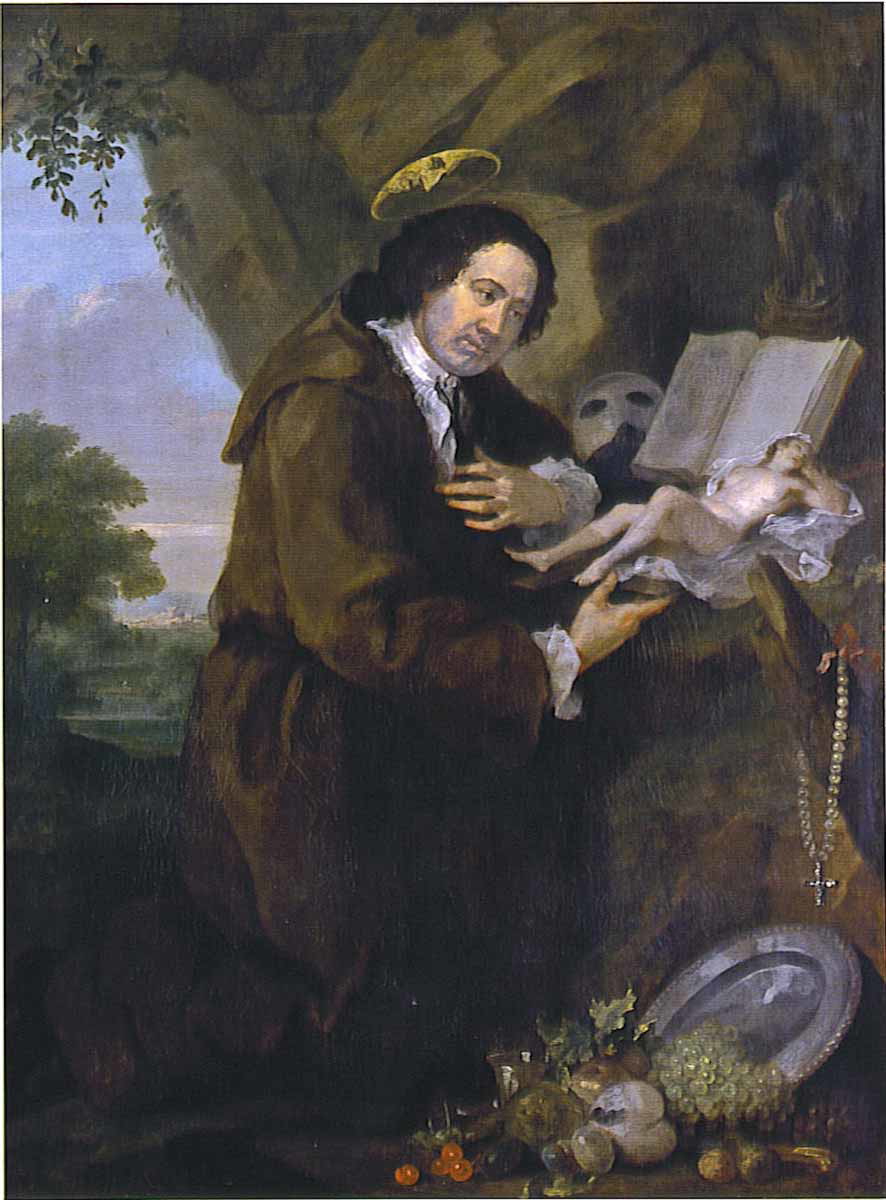

Despite dozens of moralistic images painted by Hogarth, many art historians doubt his own moral qualities and have reasons to believe that he was not as well-behaving as expected. His affiliation with the infamous Hellfire Club raises enough suspicion. The term Hellfire Club referred to several organizations in British history, all of them being exclusive clubs for male aristocracy, equally interested in political intrigues and various forms of depravity. The club’s edition, which Hogarth was affiliated with, was organized by Francis Dashwood. Dashwood arranged a gentlemen’s club parodying the structure of the Franciscan monastic order, focusing on parties, blasphemy, and other joys prohibited by the church. The organization quickly became notorious for its debauchery, orgies, and pagan rituals.

William Hogarth personally knew Dashwood and allegedly attended several meetings of the Hellfire Club. The most obvious evidence of their connection, however, is the notoriously blasphemous portrait of Dashwood painted by the artist in the 1750s. There, the club founder was presented as Saint Francis, wearing a monastic robe. However, instead of the Holy Scripture, he reads a copy of a popular erotic novel of the time and gazes intently at the figure of a nude woman instead of the crucifix.