The Ainu, native to the region of Hokkaido, are one of the oldest indigenous people in Japan. Their unique culture, language, and history predate the creation of modern Japan and set them apart from the rest of the country.

Located in northern Honshu, Hokkaido, and parts of the Sakhalin and Kuril Islands, the Ainu have upheld a distinct cultural identity for centuries in the face of increasing pressure to assimilate into the dominant culture of mainland Japan.

One of East Asia’s most overlooked people, the Ainu, have fascinating origins and a rich culture.

Origins of the Ainu

The exact origins of the Ainu people have long been debated by historians, anthropologists, and archeologists. The prevailing theory is that they are descendants of the early Jomon people, an ancient hunter-gatherer society that roamed across the Japanese islands approximately fourteen thousand years ago. The early Jomon people were famous for their use of pottery, which used intricate designs that distinguished them from later indigenous groups. Preserved remains of the Jomon people have since been studied by anthropologists who have determined that they are genetically more closely related to the Ainu than to any subsequent ethnic group that inhabits modern Japan.

Over thousands of years, the Japanese archipelago saw migrations from numerous peoples of the Asian continent, including the Yayoi people, who arrived around 300 BCE, bringing rice agriculture, metal work, and new technologies with them. While the newly arrived ethnic groups mixed with the native Jomon peoples of Japan, the isolated northern regions of the country were sparsely populated, and the Ainu who lived there carried out a less integrated way of life. This separation from mainland Japan led them to develop a unique culture that remained quite distinct, including customs and language.

Many historians believe that despite their isolated nature, the Ainu may have been influenced by neighboring cultures from the Russian Far East, particularly the Nivkh and Uillta peoples, with whom they share certain cultural and genetic traits. These shared traits have led some anthropologists to believe that the Ainu were part of a broad network of peoples who traded across northern Asia and had more in common with their neighbors to the north than those living in mainland Japan to the south.

Key Components of Ainu Culture

Throughout their pre-modern existence, the Ainu lived as hunter-gatherers with a semi-nomadic lifestyle dependent on the natural landscape. The Ainu fished extensively in the rivers of Hokkaido and hunted bears and deer in the forests. In contrast to the Yayoi peoples of the south, they did not develop rice-based agriculture and instead relied on wild plants and animals for sustenance and trade. The harsh yet bountiful ecosystem of Hokkaido greatly influenced their way of life as it discouraged settlement and persuaded a more nomadic lifestyle.

Despite this lifestyle, the Ainu built permanent homes known as chise, which were made of materials such as bamboo, wood, and straw. A collection of chise was commonly gathered together in a village called a kotan, which was made up of a few families and was often located near a river that provided food and transportation. Within the Ainu community, there existed a strict social hierarchy in which the older men of the village took on a leadership role.

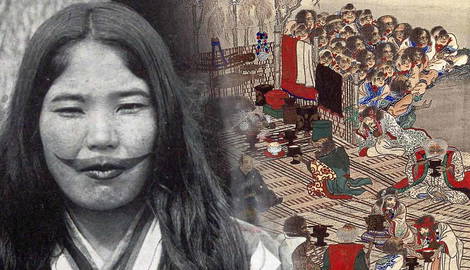

In Ainu society, men primarily hunted and gathered food, while the women of the village contributed by harvesting edible plants and weaving textiles. Women were also responsible for the practice of anchi-piri, in which women were decorated with tattoos around the mouth and hands. These markings were seen as signs of beauty and maturity. Tattoos were also thought to serve a religious purpose, as the Ainu believed that evil spirits could not enter the body after death if the mouth had been tattooed.

The Spirituality of the Ainu

The spiritual beliefs and practices of the Ainu were highly sophisticated and are one of the most unique aspects of their isolated culture. The Ainu belief system was based on animism, the belief that all aspects of nature, especially the animals, plants, mountains, and rivers, are inhabited by god-like spirits known as the kamuy. Notably, a spirit could either have malevolent or benevolent qualities depending on the interpretation of signs and symbols. The most worshiped of all the animal spirits was the bear, which was seen as the living embodiment of a mountain god.

The elaborate Iomante ceremony was one of the Ainu’s most sacred rituals and formed a key part of their religious beliefs. During the Iomante ritual, a bear cub would be taken from the wild and raised by the Ainu community, treated with reverence, and worshiped as a living embodiment of the kamuy. Once the bear had reached maturity, it would be sacrificed, and the meat would be eaten and distributed among the community, releasing the spirit from its earthly prison and benefiting the community in the process. The Ainu believed that following the sacrifice, the spirit of the bear would ascend to the spiritual world and tell the other kamuy of the kindness it experienced while living among the people, therefore securing good tidings for the village.

Aside from the bear, other animals, such as owls, wolves, and foxes, held special significance for the Ainu and were revered as gods. They held special rituals in their honor and performed dances that were intended to maintain the harmony between the world of the living and the spirit world. The spirituality of the Ainu penetrated deep into every aspect of their culture, influencing their art, mythology, and daily life.

Exploring the Ainu Language

Despite sharing a few common words and phrases with Japanese, the Ainu language is considered to be completely unique, meaning it is not related to any other linguistic group. The origins of the Ainu speech are unknown to this day. Existing primarily as an oral communication system with no written text, the language was passed down through generations of storytelling, songs, and religious rituals. As a result, the Ainu oral tradition is incredibly diverse, with epic tales known as yukar being passed down by family members.

In addition to oral literature, the Ainu communicated their beliefs through songs called uppopo, which were sung during events such as the Iomante ceremony. These songs also covered mundane topics such as daily life, nature, and historical events. For the Ainu people, singing was more than a way to pass the time; it was a method of passing vital information down to younger members of the community.

After centuries of integration and marginalization from the Japanese-speaking mainland, the language of the Ainu is considered critically endangered today. It is thought that as few as a hundred native speakers of the language remain, though efforts to preserve the language are gathering pace. Language preservation projects are underway, and the oral literature of the Ainu is being recorded for future generations.

Contact Between The Ainu and Mainland Japan

The historical relationship between the native Japanese islanders and the Ainu people is long and complex. For years, the Ainu traded goods such as animal skins, dried fish, and furs with the Japanese in exchange for metal tools and other goods. However, towards the 13th century, settlers from the mainland began to encroach further upon the sacred hunting grounds of the Ainu in Hokkaido, eventually leading to increasing conflict between the two peoples.

This conflict came to a head during the Koshamain Revolt in 1457, during which a number of Ainu rebelled against the Japanese settlers. While the revolt was crushed by the superior Japanese forces, an atmosphere of tension remained. During the Edo period, the Matsuma took control over much of southern Hokkaido and established a trade monopoly in the region, further marginalizing the local Ainu traders.

One of the most transformative periods for the Ainu came during the Meiji Restoration in 1868, when the Japanese emperor attempted to consolidate control over the disparate regions of the island archipelago. During this time, Hokkaido was officially annexed by the Japanese, and the Ainu were forced to assimilate into Japanese society. A number of their traditional customs were banned, and they were forced to learn Japanese and change their names. In 1899, the Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act was put forward as a legal framework that would help to secure the rights of the Ainu within the Japanese state, but instead, it served as a mechanism by which land belonging to the Ainu was forcibly confiscated.

The Decline of the Ainu

With the dawn of the 20th century, the forced assimilation of the Ainu into Japanese society became a key goal for the Meiji-era government. New laws disrupted the traditional way of life; lands were seized and converted for agricultural development and were settled by Japanese farmers. As a result, the Ainu were unable to make a living, and without their traditional hunting grounds, they found work on farms and in mines.

Furthermore, the Japanese government prohibited certain ceremonies from taking place, such as the bear-sending ceremony, and discouraged the use of the Ainu language entirely. As Japan continued to modernize, the academic consensus in the nation was that the Ainu were primitive people who were on the verge of extinction. This officially sanctioned viewpoint resulted in widespread discrimination against the Ainu, leading to them existing on the fringes of Japanese society. Today, the Ainu language, once spoken widely across Hokkaido, has all but disappeared, and the remaining population is as few as ten thousand people in Japan.