The Muslim conquest of Iberia began as an intervention. Under Visigoth rule since Rome’s fall, a fractious civil war broke out by the early 700s. Sensing an opportunity, in 7ll CE the Umayyad Caliphate’s army crossed the Strait of Gibraltar. At the Battle of Guadalete, the Muslims destroyed the Visigoth army and king, causing all organized resistance to collapse afterwards. By 718, the Umayyad Caliphate controlled the Iberian Peninsula, except for Basque-controlled regions and a small northern part called Asturia.

The First Decades Led to a Caliphate

Post 718 saw Iberia become a Umayyad Caliphate province with Cordoba as its capital. The enduring name of Al-Andalus emerged for the region, a translation of the Latin name Spania into Arabic. The rise now began.

The Umayyad Caliphate’s hold on Al-Andalus lasted until 750. Overthrown by the Abbasids, one Umayyad prince, Abd al-Rahman I, fled to Cordoba, establishing the Umayyad Emirate. The Emirate remained independent due to remoteness and a Berber population.

The Golden Age Begins

Al-Rahman’s reign corresponded roughly with the Islamic Golden Age (750 CE-1258 CE). Like similar Muslim areas, a wave of knowledge, enlightenment, and preservation occurred—centers of learning developed in larger cities, like Baghdad or Cordoba.

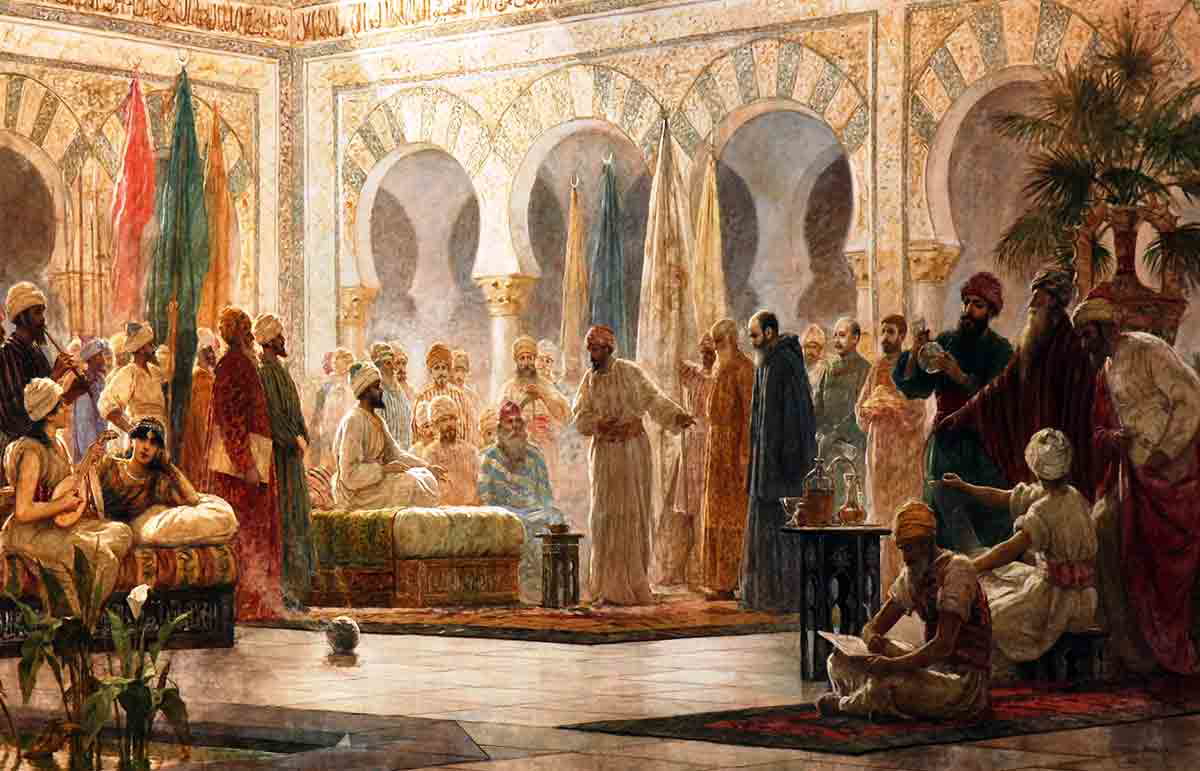

929 CE witnessed the Emirate’s change to the Caliphate of Cordoba under Al-Rahman III. As the Golden Age flourished, Cordoba transpired into one of Europe’s greatest cities. The city’s libraries became international centers of knowledge, matching Baghdad’s House of Wisdom. Advancements in algebra, medicine, philosophy, and astronomy occurred concurrently. Islamic scholars made their contributions or updated Greek or Roman knowledge. Scholars like Averroes or A-Zahrawi contributed to scholarly knowledge and medicine. Further achievements by Andalusians also refined astrolabes and contributed to algebra.

The Marvel of Cordoba

Of Al-Andalus’s cities like Seville, Cordoba became a vibrant, multicultural hub. The Umayyad rulers made Cordoba a jewel. By the 10th century, estimates reached over 500,000, with people dwelling around the city, making this one of Europe’s largest. With lavish gardens, paved streets and even street lighting Cordoba stood apart.

Cordoba grew famous for its Moorish architecture, specifically the Great Mosque of Cordoba. Renowned for its unique red and white arches, the Umayyad rulers built the mosque in 786 with later additions.

Al-Andalus, and especially Cordoba, exemplified the Spanish term “convivencia,” or roughly, peaceful coexistence. Muslims, Mozarabs (Christians under Muslim rule), and Jews intermingled on city streets. The city boasted a Juderia, or Jewish Quarter, known for its patios. Other important Andalusian cities included Toledo, Seville, Cadiz, and Granada.

Commerce and Dissemination

The Moors settling in Iberia placed them within the Mediterranean trading network. Like the Byzantines, the Andalusians connected North Africa, Europe, and the Middle East economically. Luxury, agricultural, and manufactured goods originated or changed hands in the Caliphate.

Al-Andalus’s location, combined with such a mix of peoples, led to social and cultural exchanges. Ancient Greek, Roman, Indian, and Persian knowledge passed into Christian Europe. This dissemination would later contribute to Europe’s Renaissance.

The Fracture, Decline, and Fall

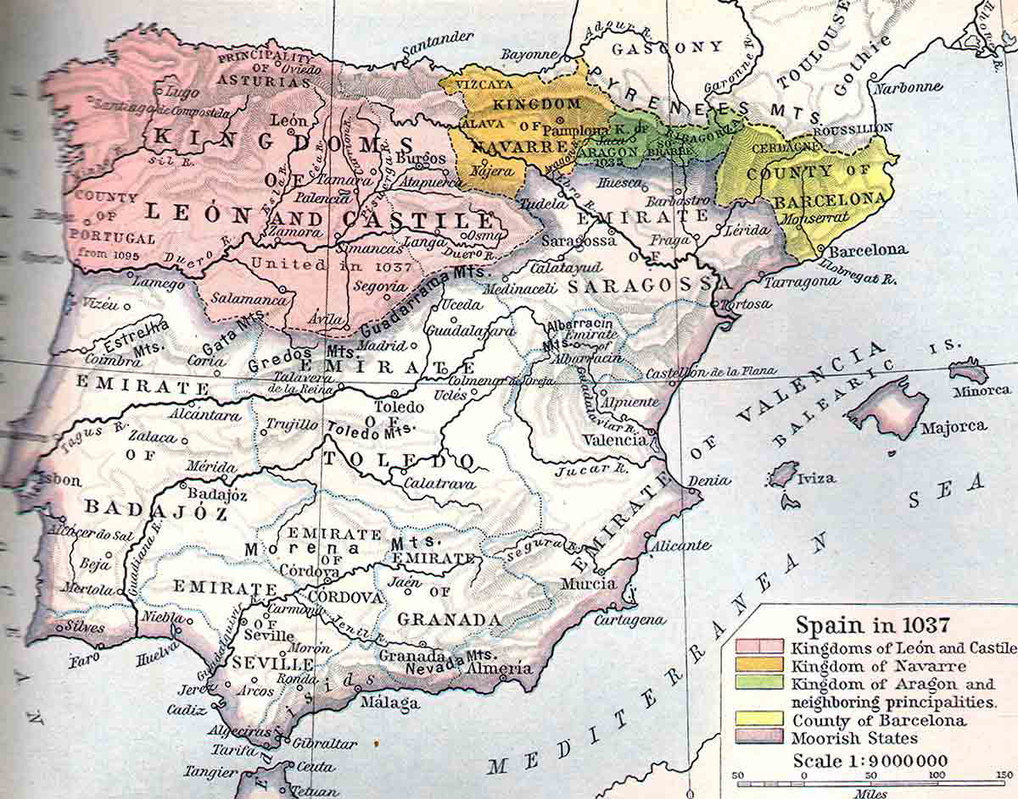

The Moor’s rise and stability ended in 1031. In the Caliphate of Cordoba, the Caliph’s assassination by a rival faction caused a twenty-year civil war. The Caliphate fractured into numerous principalities termed “taifas.” Though independent, each territory now became vulnerable to the growing Christian Reconquista. This not-quite-named crusade’s first major victory came in 1085 with Toledo’s fall. The Moor’s woes in al-Andalus only grew.

The Taifa royals invited the North African Almoravid dynasty in to fight. These new Muslim forces did, stopping the Christians in 1086. Yet the Reconquista kept gathering momentum, capturing Moorish territory.

In 1147, a second Berber Muslim dynasty, the Almohads, seized control of al-Andalus. These stricter yet tougher Muslims stabilized the conflict, if temporarily. Yet Christian victories kept coming after the 1212 loss at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa. This defeat opened Iberia for further conquest. Important centers quickly fell, such as Cordoba (1236) and Seville (1248).

The Nasrid dynasty, founded in 1232, established the Nasrid Emirate of Granada, al-Andalus’s last Muslim unit. The Christian forces continually chipped away during the 13th and 14th centuries. All effective Muslim resistance ended at the 1340 Battle of Rio Salado. Only Granada in southern Iberia stood until the final battles of 1492.

The Last Chapter

Al-Andalus’s final story played out in the last few decades of the 15th century. Granada craftily paid tribute to Christian kingdoms to buy time. The Reconquista’s final push started in 1482, inexorably grinding towards Granada’s defenses. The resulting siege ended on January 2, 1492, with Granada’s surrender. With this last Muslim bastion gone, and Spain under Christian rule, 700 years of al-Andalus ended.