As he lay dying in Babylon, Alexander the Great declared his empire would be left “to the strongest.” In the end, his empire devolved into a series of Hellenistic kingdoms. No one man was strong enough to lead one of the world’s mightiest empires by himself. Alexander had earned his epithet through the military genius, charisma, and tenacity that helped him build his empire. His admirable qualities, however, came in equal measure to his abominable ones. With his immense power and military ability came the capacity to destroy whole populations. This gave him a different epithet, one we don’t hear often: “the Accursed.”

Alexander the Great’s Legacy

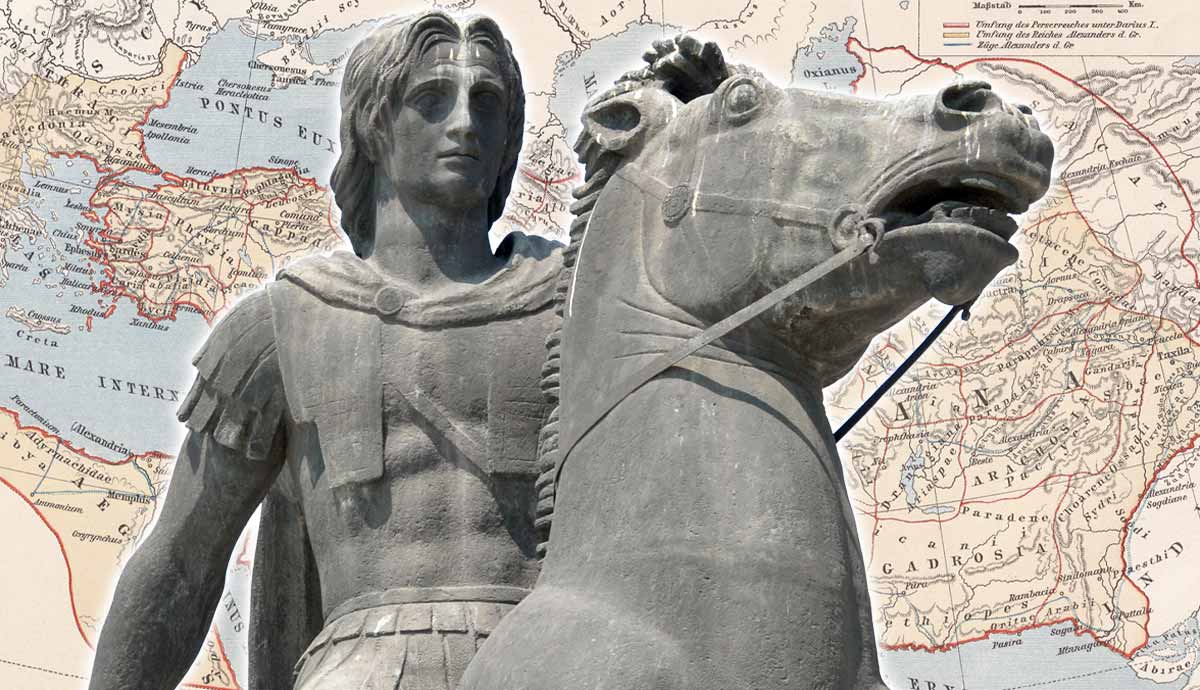

The Western world is saturated with images of Alexander the Great. Oliver Stone’s movie Alexander, paintings, and even a song by Iron Maiden attest to his legend. He is known primarily for his empire, which spanned ancient Greece, Macedonia, and all the way to modern-day Afghanistan. The legacy of this empire was the Hellenistic age. After Alexander died, no one man could control his territory. His generals, also known as Diadochi, divided the land after a series of bloody wars, which gave rise to the Hellenistic kingdoms of Ptolemaic Egypt, Seleucid Asia (mainly Syria), and Antigonid Greece. Smaller Hellenistic kingdoms also arose, including Pergamon. These regions were conscious of how they were brought into existence and disseminated Alexander’s legacy through coins, literature, and oratory propaganda.

Stories of Alexander’s greatness started during his own lifetime. His court historian Callisthenes wrote accounts of Alexander’s party being guided through the Western Egyptian desert to the Siwa Oasis by ravens. Callisthenes interpreted the ravens as divine intervention, neatly foreshadowing the Oracle’s revelation that Alexander was the son of Zeus. Alexander frequently fashioned himself after gods and heroes. Arrian describes how after making it through the hazardous Gedrosian desert, Alexander led a drunken march in imitation of a Dionysian triumph, as if he were Dionysus himself. He and his close friends feasted and drank as they rode on a double-size chariot. The army marched behind, drinking as they went, accompanied by flute players filling the landscape with music. Both Alexander and his historian went to lengths to present him as divine and ensure that all knew of him and all would remember him.

Megalomania and Godhood

Alexander made sure to remind others of his divinity and accomplished seemingly impossible feats to do so, such as conquering the rock of Aornus, a large mountain that housed a fortress on its expansive flat peak. It was almost impossible to successfully besiege it because of its immense height. Its water supply and gardens meant it was not simple to starve the inhabitants out. Even the mythical hero Herakles had been unable to conquer it, which made it Alexander’s prerogative to take it. While some modern scholars, including Fuller, assert this was a strategic move to keep his supply lines open, Arrian suggested that Alexander tried to prove his might by outdoing Herakles. This was part of a pattern of Alexander asserting himself as more powerful than gods. Being a god wasn’t just about drunken marches and flutes for him. Being a god was about power. Actions like these made sure both enemies and friends knew of his divine supremacy.

Alexander first realized his divinity at the Siwa Oasis. There, he was declared the son of Zeus-Ammon. During Alexander’s time, the Greeks and Macedonians saw declaring oneself divine as heretical and lacking humility. Even kings, like Alexander’s father, Phillip II, were only declared heroes after death. The Macedonians placed value upon the humbleness of their kings. By declaring himself a god, Alexander put a wedge between himself and his troops.

The original ‘official’ goal of Alexander’s campaign had been set out by the League of Corinth. The campaign was meant to liberate Greek cities in Asia minor and debilitate the Persian Empire as revenge for the destruction caused during the Persian Wars. After Darius III – the Persian King – was killed, the Persian army decimated, and the empire ruined, it was clear that the Asian campaign was over.

This was not so clear to Alexander. He decided first to chase Bessus, a Persian general who made a play for the throne and then went into the empire’s eastern provinces of Sogdiana and Bactria. He didn’t even stop there and attempted to go beyond the empire’s original borders into India. It was certainly not about the League’s goal at this point, but perhaps for Alexander, it never was.

Curtius describes Alexander as coping “better with warfare than peace and leisure”. It seemed that Alexander’s pothos – intense desire or longing – for conquest was stronger than any other desire. During Alexander’s reign, no coins of him were minted in Macedonia. Alexander was campaigning for most of his reign, and the Macedonians seemed to feel neglected by his lack of interest in them.

At times, his pothos was even stronger than his self-preservation. This became clear in Mali of the Punjab, where Alexander jumped into the enemy’s fortress despite knowing he had no back-up. His pothos had already outrun his reason when he decided to try to push into India after ten years of campaigning with battle-weary and homesick troops. For Alexander, conquest was his driving passion. Calling an end to this campaign would have been to deny his purpose.

At Opis, after two mutinies, Alexander the Great announced his plans to campaign in Arabia. Arrian records men shouting that if he wants to go to Arabia, he can go with his divine father instead. It was becoming increasingly clear to the men that Alexander was living more in the vision of his divine and military supremacy than in reality.

Alexander III: Legend and Human

At a symposium at Maracanda, Alexander’s men began to praise their leader’s achievements, like his role in the battle of Chaeronea, while downplaying those of his father Philip II. Cleitus the Black had been one of Philip’s senior generals and argued that Alexander was overstating his role in the battle. He also degraded Alexander for his divine pretensions, friendliness towards Persians, and his own increasing orientalism. Cleitus finished his rant with a eulogy to Philip.

Furious, Alexander ran Cleitus through with a guard’s pike. He instantly regretted his actions and sulked in his room for a few days. The legend of Alexander as a divine genius is somewhat undone by this moment of pure emotion. It is at this moment that Alexander’s secondary, subconscious motive for attaining greatness becomes visible. Alexander needed to prove to himself that he was greater than his father Phillip, the man who had originally turned Macedonia into a military and economic superpower.

In Persian literature, Alexander the Great is given the title of the ‘Accursed,’ associated with demons and the end of the world. Alexander had the entire population of the Zeravshan Valley killed for sheltering the rebel Spitamenes and his men. Alexander had a similar reaction to the population of Tyre. Tyre had initially surrendered to him, but after the Tyrians refused to let him sacrifice to Herakles in their temple to Melqart, Alexander besieged the city.

Over 8 thousand Tyrians were killed, including 2 thousand who were crucified along the shoreline. Contrastingly, he was inexplicably generous towards defeated enemies, like the Indian commander Porus. When Alexander asked him how he would like to be treated, Porus responded, “like a king.” Alexander, impressed by Porus’s valiance and worthiness as a foe, granted that Porus could continue to rule over his lands under Alexander’s empire.

The pattern in Alexander’s ambivalent behavior towards conquered enemies can be examined through his appreciation of the Hellenistic conception of heroism. Heroes were semi-divine, brave, passionate, and accomplished incredible feats, like Achilles from the Iliad. Alexander was known to sleep with a copy of the Iliad under his pillow and modeled himself after heroes like Achilles.

Porus, who was a king, led from the front, and was courageous, accorded with Alexander’s idea of a ‘heroic’ figure. On the contrary, the common people of Zeravshan and Tyre did not. Alexander centered his worldview around ideas of heroism because by becoming a hero; he could be better than his father; he could be better than everyone. Heroes were evidently allowed to murder whole populations. They just couldn’t murder other heroes.

This paradigm surfaces again with Alexander’s treatment of Persian cultural property. While there, his court burnt down the capital of Persepolis. Regardless of whether or not the destruction was caused by an accident, this was likely highly demoralizing to the Persians who lived there and the other remnants of the Persian empire. He also caused the destruction of many Zoroastrian temples. Alexander’s militarism in Asia resulted in the loss of cultural and religious material and architecture that Persians deeply regret.

Contrastingly, when Alexander happened upon the tomb of Cyrus the Great at Pasargadae and found it desecrated, he was deeply distressed. He ordered that the Magi guarding it be arrested and tortured and the tomb restored. Destroying the cultural inheritance of most Persians was no problem for him, but the ruin of the heroic Cyrus the Great’s tomb was.

Alexander III: Great or Accursed?

Alexander III of Macedon was never merely ‘Alexander the Great’. He was also Alexander the Accursed, the Conqueror, the Murderous, the God, the Heretical. History rarely ever comes down to the present with a holistic and accurate account, and some histories will never look the same to two different perspectives. While the legend of Alexander III as the West has received it through media is amusing, interesting, or inspiring, it is not the only legend of this heroic warrior that exists. By understanding different perspectives on him, it is possible to see Alexander for the multifaceted person he may have been.