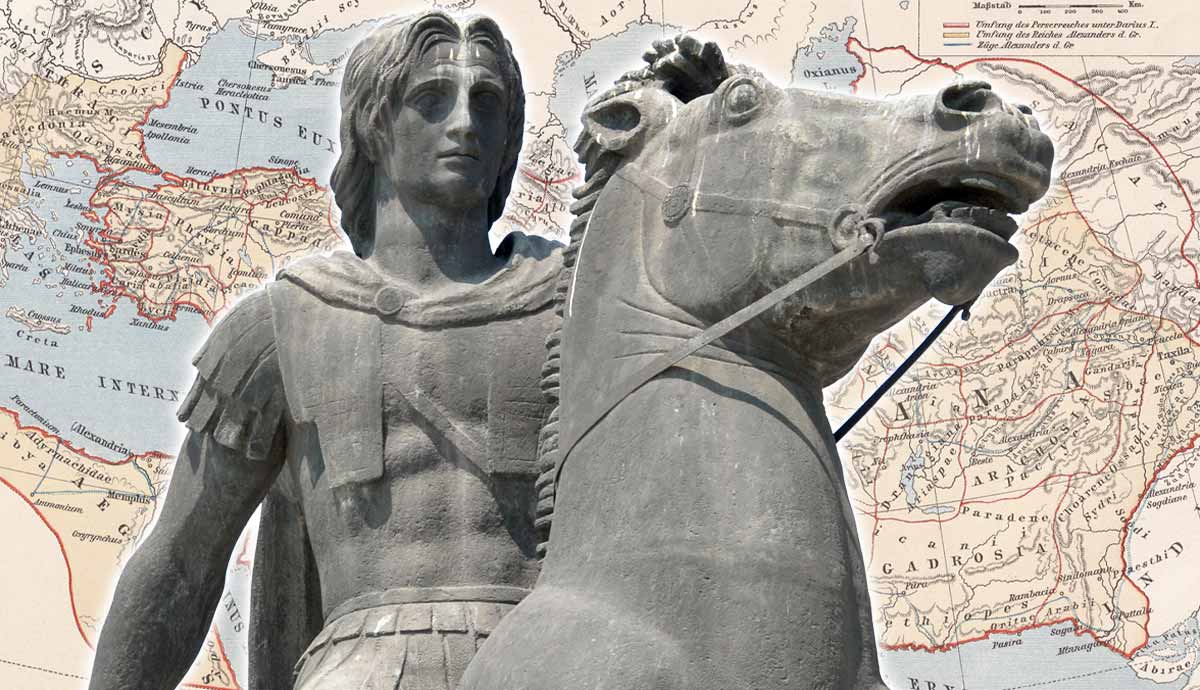

Alexander the Great is known for building one of history’s largest empires, stretching from his hometown of Macedonia all the way to northwestern regions of India. In his short life Alexander encountered some of the era’s greatest thinkers. Tutored by Aristotle, meeting the famous Cynic Diogenes and later engaging with Eastern sages, these philosophical encounters likely shaped him in various ways and contributed to the myths and legends surrounding his reign.

A Tutor Fit for a King

As a youth, Alexander was often described as being unyielding and headstrong, unwilling to submit easily to authority, whether from his father or his teachers. Plutarch, the 1st century CE Greek historian, writes in his Life of Alexander that Philip II of Macedon, upon recognizing his son’s independent nature, quickly realized that direct commands were often met with resistance. Instead, Alexander had to be reasoned with before he would accept anyone else’s authority.

Understanding that his education required a tutor of exceptional ability, Philip sought out Aristotle, a brilliant student of the philosopher Plato. At this time, Aristotle was not yet the renowned philosopher he would later become, but he had already established an impressive reputation as a preeminent thinker. In hiring him, Philip hoped Aristotle would instill his broad knowledge and Hellenic ideals in the future Macedonian king.

There is much scholarly debate about the level of influence that Aristotle might have exerted on the young Alexander, and how far we can trace his teachings in Alexander’s later actions, policies, and beliefs. Contemporary sources for the life of Alexander are rare, and the later sources are obscured by the growing myths that escalated after his death. While we cannot say for sure what kind of influence Aristotle had on his pupil, there are several interesting parallels in Alexander’s later life that could have their roots in these lessons with Aristotle. Certainly, this early meeting helped enhance the narrative of Alexander as a philosopher king, which would develop and grow in literature and history after his death.

An Early Education: Aristotle and Alexander in Mieza

While we do not have contemporary sources that detail their time together, we know that from the estimated ages of 13 to 16, Alexander studied under Aristotle in Mieza, a secluded sanctuary in Macedonia. Plutarch details Alexander’s early education under Aristotle: the Greek philosopher is said to have taught Alexander a broad and rigorous curriculum, reflecting his own diverse interests. The future king likely studied philosophy and ethics, politics and rhetoric, literature and mythology, as well as military strategy and logic—topics that matched Alexander’s need for reasoned argument and debate.

Aristotle cultivated in Alexander a deep interest in not only Greek literature and philosophy but also the burgeoning scientific studies of the time. Plutarch claims that Alexander’s love of medicine and the art of healing was instilled in him by Aristotle, and that he shared an interest not only in the theory of medicine but also its practice, often attempting to tend to his friends when they were sick, prescribing them treatments and regimens.

Aristotle had an interest in botany and zoology that he likely shared with his student, and Alexander pursued these interests on his later campaigns—in which he paid great attention to collecting scientific and geographical knowledge. He instructed his officers, including Callisthenes, his court historian, to document new plant and animal species they encountered on his conquests, sending back numerous specimens to Greece to be studied.

His army mapped vast areas, and he instructed men to take notes on rivers, mountains, and climatic conditions, vastly improving Greek knowledge of Asia. This information became a vast resource for future generations, with the founding of the Alexandrian School, and the Library of Alexandria—established by the Ptolemies after Alexander’s death—benefiting greatly from this accumulated knowledge and preserving much of the research that originated during his conquest.

Additionally, Aristotle is said to have fostered Alexander’s admiration for The Iliad, further inspiring his identification with Achilles, whom he claimed descent on his mother’s side. One of Alexander’s generals claimed that he always slept with a dagger and a copy of The Iliad—supposedly gifted by Aristotle—under his pillow. Aristotle’s Homeric tutelage likely helped develop Alexander’s sense of himself as a heroic figure akin to the protagonists of these epics, further spurring his desires to supersede his father and countrymen, gaining unparalleled glory like his childhood heroes.

Alexander and the Integration of Subject Peoples

Alexander is often noted for his efforts to integrate the lands he conquered rather than merely ruling over them. In this regard, he appears to have strayed from the teachings of his mentor. Plutarch, in On the Fortune or the Virtue of Alexander, writes that Aristotle instructed Alexander to treat the Greeks as if he were their leader and other peoples as if he were their master, and in fact to treat them as though they were plants or animals. Plutarch claims that Alexander did not heed this advice, instead viewing himself as a “heaven sent governor” and “mediator for the whole world,” bringing men together and uniting them in one community (Plutarch, De Alex, 1.6).

Throughout his reign, Alexander adopted Persian customs and encouraged intermarriage between his officers and Persian noblewomen, exemplified by the mass wedding at Susa in 324 BCE. He himself married Stateira II and Parysatis, the daughters of the Persian leaders Darius III and Artaxerxes III. Alexander’s exact beliefs and intentions with these actions are unknown to us, but it seems more plausible that these decisions were born of the practical necessity of consolidating and administering a vast empire, rather than truly altruistic motives and a belief in the unity of all men.

This attitude is often presented as a removal of his tutor Aristotle, but likely Aristotle was already not quite the pivotal force in Alexander’s life, later analysis has suggested. Despite the marked-ness of this meeting to later readers, Aristotle never mentions Alexander directly in any of his works, nor even alludes to his time spent in Macedonia. The pre-eminence that they both reached perhaps has led to an over-estimation of their potential influence on one another, with later historians and writers eager to attribute philosophical depth to Alexander’s rule.

The Conqueror and the Cynic

One of the most famous anecdotes about Alexander is that of his meeting with the philosopher Diogenes, considered to be one of the founders of Cynicism. Cynicism as a philosophy predominantly emphasized the rejection of superficial desires—such as power, possessions, and one’s own reputation—in favor of a life of honesty, freedom, and asceticism. Cynics believed that happiness came from stripping life down to its essentials and not becoming absorbed in the pursuit of material possessions or personal glory.

Plutarch tells the story of Alexander’s meeting with Diogenes in Corinth, circa 336-335 BCE. The encounter supposedly took place shortly after Alexander was declared Hegemon of the Greek states by the Corinthian League, as he was readying to set off on his great campaign against Persia. Plutarch writes that many statesmen and philosophers came to Alexander to give him their congratulations, and that he had expected the philosopher Diogenes to be amongst them.

However, Diogenes apparently took no notice of Alexander and made no effort to seek him out. Curious, Alexander went in search of Diogenes and found him lounging in the sun. Famously, when Alexander asked if there was anything he could do for him, Diogenes simply replied, “Yes, stand a little out of my sun.” Plutarch writes that Alexander was so struck by this response and so greatly admired the boldness of this man that he said to his followers, “But verily, if I were not Alexander, I would be Diogenes.”

Like many such stories of Alexander, it is possible that this story is more anecdotal than historical. While it is entirely possible that the two met during the period recorded, the story fits perhaps too well within the tradition of philosophical anecdotes intended to highlight a moral lesson to be entirely historical. Regardless of its historicity, the meeting serves as an interesting clash between two worldviews, with Diogenes and Alexander symbolizing two opposite extremes. Diogenes was famous for living in a barrel and eschewing all forms of material goods, whereas Alexander, after their meeting, went on to become one of the richest and most powerful men in history.

If we were to attempt to uncover a moral lesson that the account of this encounter may be trying to suggest, it would perhaps be that true freedom does not come from ruling over others, but rather from needing nothing at all. For even Alexander, poised to become one of the world’s most powerful men, had to admire the unshakeable independence and self-assurance of this humble Cynic.

Dandamis and the Gymnosophists: Alexander and Eastern Philosophies

During his short life, Alexander’s campaigns led him from Macedonia through the Persian Empire and beyond, toppling dynasties, founding cities, and finally making it all the way to India. Several ancient sources discuss Alexander’s meeting with the Gymnosophists, a Greek term that broadly applied to Indian ascetics who lived lives of extreme simplicity and philosophical reflection, often Jain, Buddhist, or Hindu sages.

Plutarch describes how Alexander captured ten of the Gymnosophists who had been involved in a revolt against him. They had been reported to be wise and concise in their answering of questions, and Alexander decided to put this to the test. He put to them a series of riddle-like questions, declaring that whoever made the first incorrect answer should be put to death. After answering all the questions and conferring with the judge he had appointed, it became clear that, according to his own rules, none of the Gymnosophists could be executed as they had all provided satisfactory answers.

Arrian, a Greek historian and statesman writing in the 2nd century CE, in Book VII of his Anabasis of Alexander, tells of Alexander’s encounter with one of the oldest of the Indian philosophers, a man named Dandamis. Dandamis refused to come and meet with Alexander when his presence was requested and would not allow any of his followers to do so either. He said that there was nothing he wanted from Alexander as he was already content with what he had, and that the restless and never-ending wanderings of Alexander’s own attendants had no appeal to him. He stated that the country in which he lived was sufficient for him, and when he died, he would be released from his body, unable to partake further in any material wealth.

Arrian also tells a story in which Alexander encounters a group of Indian philosophers while they were walking in an open meadow, where they spent much of their time, and who upon seeing the conqueror, began to stamp their feet on the ground. Questioning the meaning of this behavior, Alexander asked his translator to speak to the men and ask them what it was that they were doing. Arrian quotes the response of one man:

“O king Alexander, every man possesses as much of the earth as this upon which we have stepped; but thou being only a man like the rest of us, except in being meddlesome and arrogant, art come over so great a part of the earth from thy own land, giving trouble both to thyself and others. And yet thou also wilt soon die, and possess only as much of the earth as is sufficient for they body to be buried in” (Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander, Book VII, Chapter 1).

These sources display Alexander as impressed with the unwavering self-assurance of these philosophers, unwilling to compromise themselves and their beliefs in the face of such astounding power, and able to answer his questions without fear or uncertainty. Like Diogenes, these sages refused to be awed by Alexander’s power. Their asceticism contrasted sharply with his boundless ambition, emphasizing the impermanence of material wealth and conquest. Given that these stories come shortly before his early death in Babylon in 323 BCE, and the gradual disintegration of his empire, they contain a sense of tragic irony, anticipating Alexander’s looming downfall.

The Philosopher King: Alexander in Persian Literature

The legend of Alexander has often been altered and adapted throughout history, told by many different authors and translated into many languages. In Persian literature, the story of Alexander went through a number of alterations, and gradually the image of the violent conqueror was transformed into that of an idealized ruler and philosopher-king.

In Zoroastrian, middle Persian texts, Alexander is often referred to as gizistag or gujastak, meaning “accursed,” and he is derided for his violent ways. For example, in the Ardāy Wirāz Nāmag, Alexander is blamed for the temporary destruction of Zoroastrian religion, claiming that Zoroastrianism had been flourishing for 300 years before Alexander’s conquest, during which he burned the Avesta—their sacred scriptures, killed their priests, and desecrated their religious sites.

However, in the Persian Shahnamah (Book of Kings) by Firdawsi c. 977-1010 CE, a national epic of greater Iran, Alexander (Iskandar in Persian) is depicted as a wise and just ruler who seeks knowledge and wisdom on his journeys. After defeating Dara (Darius III), Alexander ascends the Persian throne and sets off on a path of self-discovery, gaining knowledge from philosophers and sages and seeking the legendary Fountain of Life. In this book, he comes to exemplify the Persian ideal of a just ruler (padshah-I adil), one who rules through wisdom rather than mere force.

The 12th century Persian poet Nizami Ganjavi’s Khamsah is written in five long narrative poems, the fourth of which is titled the Iskandarnamah (Book of Alexander). It is divided into two main sections, the Sharaf-nama (Book of Glory), which focuses on Alexander as a unifier of different cultures and peoples, and the Iqbal-nama (Book of Fortune), which emphasizes Alexander’s philosophical pursuits and spiritual journey as he seeks wisdom and understanding. Similar to Firdawsi in the Shahnamah, Nizami portrays Alexander as an almost prophet-like character, engaging in dialogues with philosophers in an attempt to become the ideal ruler.

Conclusion

The legend Alexander created in his own life, as well as the myths that developed after his death, transformed him into an almost fictional character. His immense success and early death further contributed to the romantic image of him as a Homeric hero and almost otherworldly figure, a narrative so gripping and powerful that it has captured the imagination of writers, historians, and philosophers for centuries.

Alexander’s life provides fertile ground for the speculation of many philosophical questions. His story has been used variously to consider topics such as the nature of kinship and morality, the unification of cultures, asceticism, cynicism, and the individual pursuit of power and glory. Untangling the real Alexander from the myths that surround him appears to be a near-impossible task, and we will likely never be able to fully separate his own philosophies from those later attributed to him. However, the complex interweaving between myth and reality is partly what has made the story of Alexander so compelling and has allowed him to be a vessel for philosophical exploration, through which different eras have considered their own ideals, fears, and aspirations.