When something is 100% certain, we often say that it’s “as sure as the sun rises in the east.” That’s because the sun is the most dependable thing in all of human history. Except perhaps in Japanese mythology. Personified by the goddess Amaterasu (lit. “Heaven Shining”), one of the most important deities in the Shinto pantheon, the Japanese sun has been known to be a little fickle from time to time. Or perhaps she was just reacting properly to challenging circumstances. Here is her story.

The Sun Rises Late

It took a while for Japan to see its first sunrise. According to Kojiki (An Account of Ancient Matters), the oldest text in Japanese history, when the heavens and earth first formed, three generations of gods appeared and then “concealed themselves.” The fourth generation, however, stuck around. A sun deity still was not among them, but the group did contain the siblings Izanami and Izanagi. They created the first Japanese island when Izanagi plunged his spear into the primordial waters below the heavens and a drop fell from his weapon when he pulled it out, creating the isle of Onogoro (Yasumaro, 2014, pp. 7-8).

Descending onto the island, the siblings got married and proceeded to create the rest of Japan via intercourse and childbirth. Islands, trees, mountains and all natural features were all born from Izanami. Unfortunately, one of Izanami’s children was a god of fire who fatally burned her when coming into the world. Stricken with grief, Izanagi ventured into the Underworld to retrieve his wife. Just like in Orpheus and Eurydice, something went wrong, and Izanagi ended up angering the undead Izanami who used hell-hags to chase him out. After his misadventure in the land of the dead (considered impure in Shinto), Izanagi decided he needed a cleansing bath (Yasumaro, 2014, The Kojiki, pp. 13-16).

Washing himself in a river, he created a total of 14 gods, chief among them Amaterasu, who was born when Izanagi washed his left eye. Cleaning out his right eye gave us Tsukiyomi, the deity of the moon, while blowing his nose birthed Susanoo, the fearsome god of winds and storms.

A Murder Estranges the Sun and the Moon

All grown up, Amaterasu ruled the heavenly plains while keeping an eye on the goings-on below. Hearing rumors of Ukemochi who took on the role of the goddess of food, Amaterasu sent Tsukiyomi (also known as Tsukuyomi) down to Earth to wait on her. According to the Nihongi chronicle of myths, legends, and genealogies, Ukemochi prepared for the visit by arranging a wonderful feast using her mouth. Facing the sea, she parted her lips and brought all manner of fish into the world. Facing the land, she created boiled rice. Facing the mountains, land animals came to life from her mouth. All were then arranged into delicious dishes that filled up more than 100 tables. Unfortunately, Tsukiyomi was not pleased with the goddess’ offering.

“Filthy! Nasty!” he yelled, accusing Ukemochi of feeding him vomit. “That thou shouldst dare to feed me with things disgorged from thy mouth.” Then Tsukiyomi pulled out a sword and killed Ukemochi. Amaterasu never forgave Tsukiyomi for that, proclaiming: “Thou art a wicked Deity. I must not see thee face to face” (Aston, 2008, p. 32). Ever since then, the sun and the moon became separate, always keeping their distance from each other. As for Ukemochi, her dead body sprouted food meant for humans like wheat, rice, millet, and beans (Aston, 2008, p. 33). Even in death, the gracious deity continued to provide.

The God of Wind Angers the Sun

After having seemingly proven his non-antagonistic intentions, Susanoo was welcomed by Amaterasu to the heavenly plains. However, his wild nature (befitting a deity whose name has been translated by Gustav Heldt as “Rushing Raging Man”) eventually got the better of him. While under the influence of drink, Susanoo ruined Amaterasu’s rice paddies, burying the ditches around them, and then defecated in the great hall where his sister held her harvest festival.

Many would probably consider the toilet prank to be the worst of all, but the agricultural destruction might have been more deadly. Many centuries later, after the death of Emperor Chuai, the imperial court made a list of the greatest sins possible to identify which evils they had to eliminate in order to purify the land. Destroying rice paddies and ditches was near the top of that list, sharing the designation of a great sin with transgressions like incest, flaying alive, or bestiality (Yasumaro, O., 2014, The Kojiki, 113).

Amaterasu tried to downplay Susanoo’s behavior, blaming it on the wine. “As for his ruining the paddy ridges and burying their ditches, my mighty brother must have done this because he thought good land was going to waste,” she proclaimed (Yasumaro, 2014, p. 22). That only seemed to embolden Susanoo. Later, while Amaterasu was overseeing the work in her sacred weaving hall, Susanoo lobbed a flayed horse inside, scaring one of the weaver maidens into accidentally pricking herself with a needle, which ended up killing her. This time, Amaterasu had enough.

The Day the Sun Disappeared

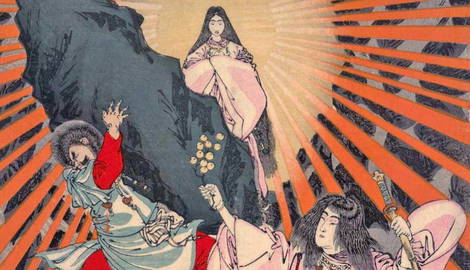

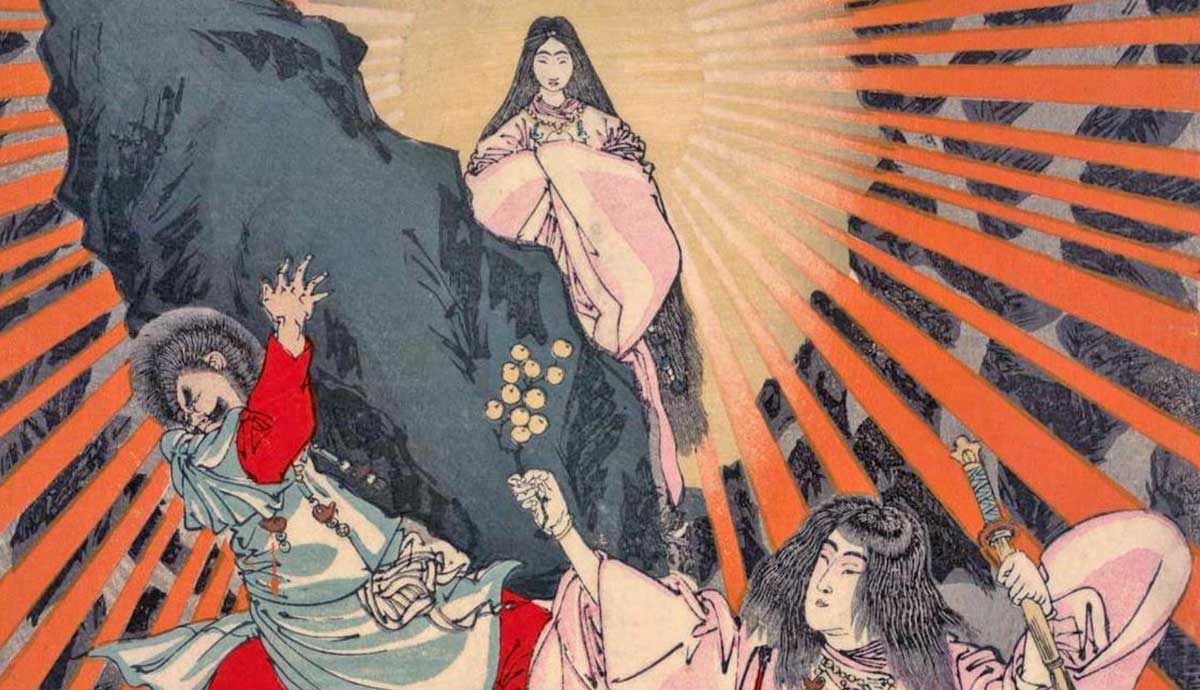

Angry at her brother, Amaterasu secluded herself in the Heavenly Rock Cave, blocking the entrance to it with a boulder that no other god could move. Because she was the personification of the sun, this threw the world into eternal night, drawing out hordes of demons. All the other gods got together to find a solution. One of them, the goddess Ame-no-Uzume, had an idea. Her unorthodox plan was to do a frenzied, comedic dance on an overturned barrel, exposing her breasts and eliciting great laughter from her heavenly audience.

Eventually, intrigued by the noises outside, Amaterasu moved the boulder to her cave to have a peek when one of the more powerful gods pulled her out. Everyone then implored her to stay and bring light back to the world. Amaterasu agreed (Yasumaro, 2014, The Kojiki, pp. 23-24). Susanoo, on the other hand, was banished to Earth where he reformed his image by slaying Yamata no Orochi, a dreaded eight-headed serpent who kept devouring young maidens. After that, Susanoo became a respected and feared god and even obtained a legendary sword out of the ordeal. Ame-no-Uzume’s dance, on the other hand, became the mythical origin of kagura theater, possibly the oldest form of performing art in Japanese history.

The Sun Sets Her Eyes on Earth

Amaterasu eventually decided that the lands below the heavens should be under the control of the heavenly gods. Her actual words, according to the Kojiki, were: “The realm of plentiful reed plains, of a thousand and five hundred long autumns of fresh rice ears, will be a realm ruled by our heir” (Yasumaro, 2014, p. 41). The sun goddess sent the young Ame-no-Wakahiko ahead as a scout but he ended up liking Earth so much, he decided to ignore his mission and stay there. Amaterasu sent a messenger bird to check up on him so Ame-no-Wakahiko shot it with an arrow that kept going and eventually reached the heavens themselves.

Finding the blood-covered arrow, the gods sensed that something was amiss, so they sent the arrow back, which immediately hit and killed Wakahiko. During Ame-no-Wakahiko’s funeral, the god Ajisukitakahikone showed up looking exactly like the deceased. Being mobbed by mourners who thought that Wakahiko came back to life, Ajisukitakahikone was so insulted by being compared to a corpse that he pulled out his sword, called the Great Leaf Reaper, and destroyed the mourning hut, kicking it away whereupon it became a mountain known as Mount Mourning (Yasumaro, 2014, p. 44). This is why it is considered impolite to point out physical similarities between living and deceased people in Japanese society.

Amaterasu eventually got her conquest under control, preparing the physical realm for the arrival of heavenly gods, and ultimately sending her grandson Ninigi down to Earth. Today, he is considered the ancestor of all Japanese emperors who for millennia claimed direct descent from him and, more importantly, his grandmother: the moon-shunning, flayed horse-fleeing, eternal darkness-bringing goddess of the sun. Modern Japanese emperors no longer consider themselves divine, but the link between the imperial household and Amaterasu remains strong, with some considering the sun goddess a representation of Japan itself.

Sources

Translated by Aston, W. G. (2008). Nihongi Volume I – Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Cosimo Inc. (Original translation published 1896).

Yasumaro, O., translated by Heldt, G. (2014). The Kojiki, An Account of Ancient Matters. Columbia University Press.