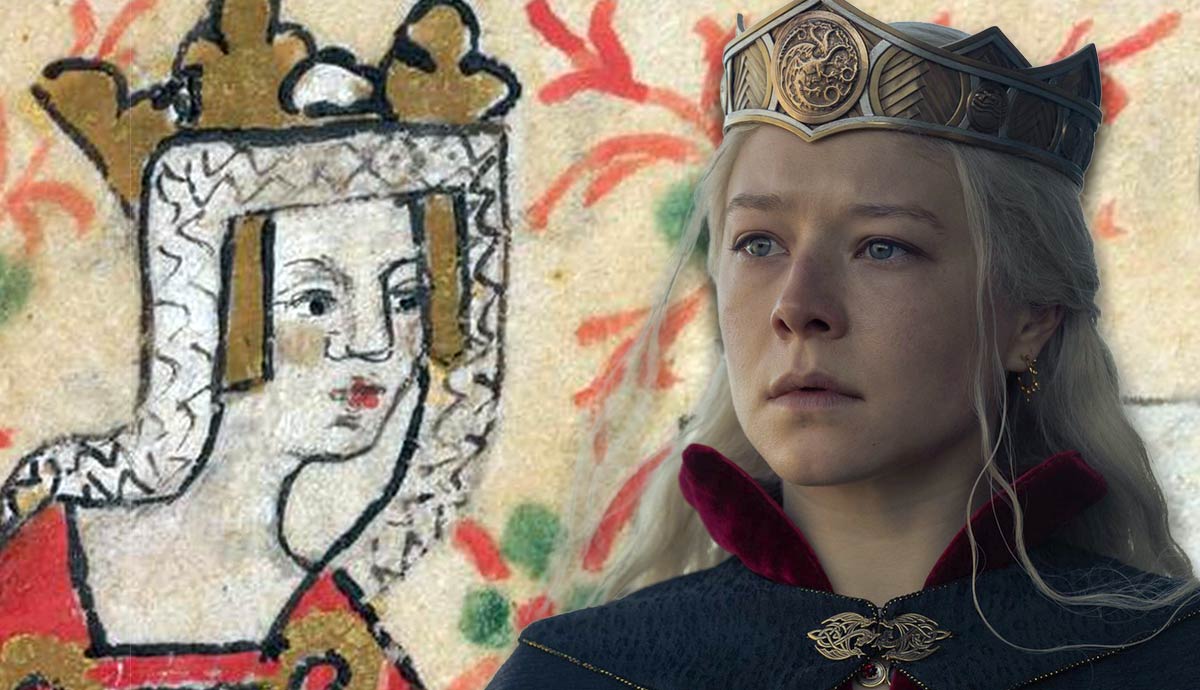

It is no secret that author George R.R. Martin looked to the Wars of the Roses as inspiration for A Game of Thrones. The HBO prequel series, House of the Dragon, is similarly inspired by another period of English history. Lacking a (living) son, Henry I named his daughter Matilda as his heir. When he died, the nobility turned instead to her cousin Stephen, who had the distinct advantage of being a man. This led to “the Anarchy,” a civil war that lasted nearly two decades.

Henry Takes the Throne

In November 1120, the succession of the English throne was thrown into question. The only legitimate son of King Henry I, William, died in a shipwreck while crossing the English Channel. Henry was the third son of William the Conqueror, who had taken control of England less than a century earlier, in 1066. His eldest son, Robert, inherited the Duchy of Normandy, and his second son, William, inherited the English throne. Henry, as the third and youngest son, was left with little to inherit.

This all changed on August 2nd, 1100, when William II (Rufus) was (accidentally?) killed while hunting. He had no children, so the crown of England should have passed to his elder brother, the Duke of Normandy, but Robert was away on the First Crusade, so Henry took the opportunity presented to him and was crowned King Henry I of England three days later.

When Duke Robert returned and challenged his brother, they arranged a short-lived settlement which compensated him for renouncing his claim to the English throne. A few years later, Henry invaded Normandy, took Robert prisoner, and reunified their father’s lands as both the Duke of Normandy and the King of England. Robert spent the rest of his life, 29 years, imprisoned.

Henry’s rule was a relatively quiet one—for England at least. He fought over Normandy repeatedly, against Louis VI of France, Fulk of Anjou, and his own nephew, William Clito, but emerged triumphant in early 1120. His wife, Matilda of Scotland, had died two years previously, but he felt his line secure with a son and a daughter.

The daughter, Matilda (sometimes called Maud, to differentiate her from her mother, her rival King Stephen’s wife, and the many other Matildas in the family), had been sent to the Holy Roman Empire to wed Emperor Heinrich V in 1114 when she was twelve years old. As we see in the world of House of the Dragon, royal marriages were used to cement political and familial alliances. Girls and women had virtually no choice in the matter, but even princes were subject to the needs of the state.

She took her position as empress very seriously, never relinquishing the title despite the fact she lost the position when her husband died in 1125. Without children, she had no reason to stay in the empire so she returned to England.

Dynastic Plans

Matilda had become her father’s heir on her brother’s death five years previously but, at the time, there was little expectation that she would actually succeed him. Henry had remarried in 1121, and his young wife Adelaide might still produce a son. Unlike Viserys and Alicent, however, this couple never had any children.

When she was widowed, he quickly arranged a marriage for her with Geoffrey Plantagenet, the 13-year-old Count of Anjou. Matilda was not happy with the marriage: it greatly reduced her status (though she still insisted she be called empress).

Once Geoffrey reached adulthood, she managed to work with him begrudgingly, particularly as it related to maintaining her familial inheritance to Normandy. They also had three children together, the eldest, Henry, was born in 1133.

The English barons whom Henry I had forced to swear loyalty to her and her heirs as his successor must have been relieved—the crown need not pass to a woman after all. But, Henry was confident in his daughter as his heir and so did not rearrange the succession in his grandson’s favor.

Things may not have been different if he had, since the man who claimed the throne at Henry’s death just two years later, Stephen of Blois, had an equal claim to the throne to his cousin Matilda; they were both grandchildren of William the Conqueror, Stephen by the Conqueror’s daughter Adela. More important to many, he was a grandson.

Claiming the Crown

When Henry I died in December 1135, Matilda and Geoffrey were in Normandy. Like Rhaenyra in House of the Dragon, the fact she was not in the capital immediately disadvantaged her claim. When news of the king’s death reached them, the two moved to gain control over several fortresses in the Duchy, thinking that would give them a better position from which to secure England.

Unfortunately, none of Matilda’s supporters were in London to argue her case. It was quickly obvious that even those who had promised to support her were not willing to follow through.

In the meantime, Stephen of Blois crossed the Channel and arrived in London in time to argue his position that he was the rightful heir and that Henry had been wrong to force the barons to swear loyalty to a woman. His brother Henry, the Bishop of Winchester, lent his (and thereby the Church’s) support. Lastly, Stephen was granted access to the treasury by the lord chancellor, a sure sign of support by the aristocracy. Stephen I was crowned on December 22, 1135.

On the advice of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Pope Innocent II sent his approval, essentially guaranteeing Stephen’s legitimacy. Not unexpectedly, Stephen faced rebellions early in his reign, but they were put down fairly quickly. By the Spring of 1138, it seemed England would be at peace, with Stephen as king. Matilda and Geoffrey had taken control of most of Normandy, which Stephen did not dispute.

“Christ and His Saints Slept”

In the summer of 1138, Robert of Gloucester, an illegitimate son of Henry I, publicly renounced his oath to Stephen and declared in favor of his half-sister, the Empress Matilda. This prompted rebellions to again spring up across England, this time with some level of organization from Matilda’s camp. Further support came from Dowager Queen Adeliza, who offered her home of Arundel Castle as a base of operations for her step-daughter. Unlike Alicent, Adeliza had no sons to support and so had no reason to dispute the intended succession. Stephen soon heard where Matilda was and besieged the castle.

It was a short siege; Stephen’s brother, Bishop Henry, negotiated for Matilda’s release. The details have not survived, so why Stephen gave up his rival at this point is as good as unknown. After this, the Empress moved her headquarters to Gloucester and was able to hold control over much of southwestern England. The support she gained after this seems to have come more from opposition to Stephen than an endorsement of her own claim, but she saw this as no reason to turn them away.

In February 1141, Stephen was captured by an army led by Robert of Gloucester. Empress Matilda started arrangements to be crowned and negotiated oaths of fealty from those who were willing to change sides in her favor. However, while King Stephen was imprisoned, his wife (also confusingly called Matilda) took charge of the cause and was reassured when the people of London refused the empress entry to the city in June 1141.

Shortly after she was forced away from the capital, Robert was also captured by Queen Matilda’s forces. Both sides refused to give any ground, until they were convinced to do a simple prisoner exchange in November 1141. Fighting continued and Stephen’s forces captured the empress in the autumn of 1142. She escaped shortly before Christmas, leaving the grounds on a horse shod backward to confuse anyone trying to track her.

From this point, the war ground on for years, the empress making gains here and King Stephen there, but nothing decisive enough to end the war. The fighting was so destructive to the English countryside that it caused a famine. The people, as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says, felt so abandoned by both governments that “it was said openly that Christ and his saints slept.”

The Plantagenet Dynasty

Little changed over the next few years, but in 1147 things began to shift: Robert of Gloucester died, leaving Matilda without her most important general. Both sides also lost soldiers and leaders to a cause they found more worthy, the Second Crusade. In Matilda’s camp, the focus shifted away from her claim to the throne in favor of that of her eldest son, Henry, a move supported by the empress herself.

At 14 years old, Henry had already established that he favored his inheritance from his mother by styling himself Henry FitzEmpress (son of the Empress) and ignoring his father’s name and title. In that year, with all of the self-confidence of a teenager who cannot imagine things going the wrong way, Henry put together an army in Normandy and crossed the Channel with the intent of taking his throne. All of this was without his mother’s knowledge.

Henry had not planned his invasion well. One gets the feeling that he expected an outpouring of support as soon as he landed, but the reality was that he had few plans, little support, and not even enough money to pay his soldiers. They were captured and, rather than threaten them as enemy combatants, Stephen treated them as errant children. Stephen paid the men and sent Henry home to his mother.

Henry returned to England six years later, with his mother’s war chest and soldiers. He had also quietly negotiated with members of the English nobility, giving him much-needed political support. A couple of small battles showed Stephen that Henry had come a long way since his previous attempt, prompting the beginning of negotiations to end the more than two decades of war.

The Treaty of Wallingford was signed on Christmas Day 1153. Henry did not immediately get the throne but became Stephen’s heir. He did not need to wait long to inherit: Stephen died just ten months later. Henry II was crowned on December 19, 1154, beginning the Plantagenet Dynasty who ruled England for centuries to come.