The Arctic might seem like a frozen, empty frontier, but people have been moving through it for thousands of years. Long before maps or GPS were ever invented, Indigenous communities crossed sea ice, tundra, and winding fjords from memory, with the kind of knowledge that only comes when living at one with the land. These were intentional journeys made with purpose, guided by survival needs, seasonal rhythms, oral tradition, and an intimate understanding of the environment. Trade, survival, and culture all played a role in shaping the ancient routes they took.

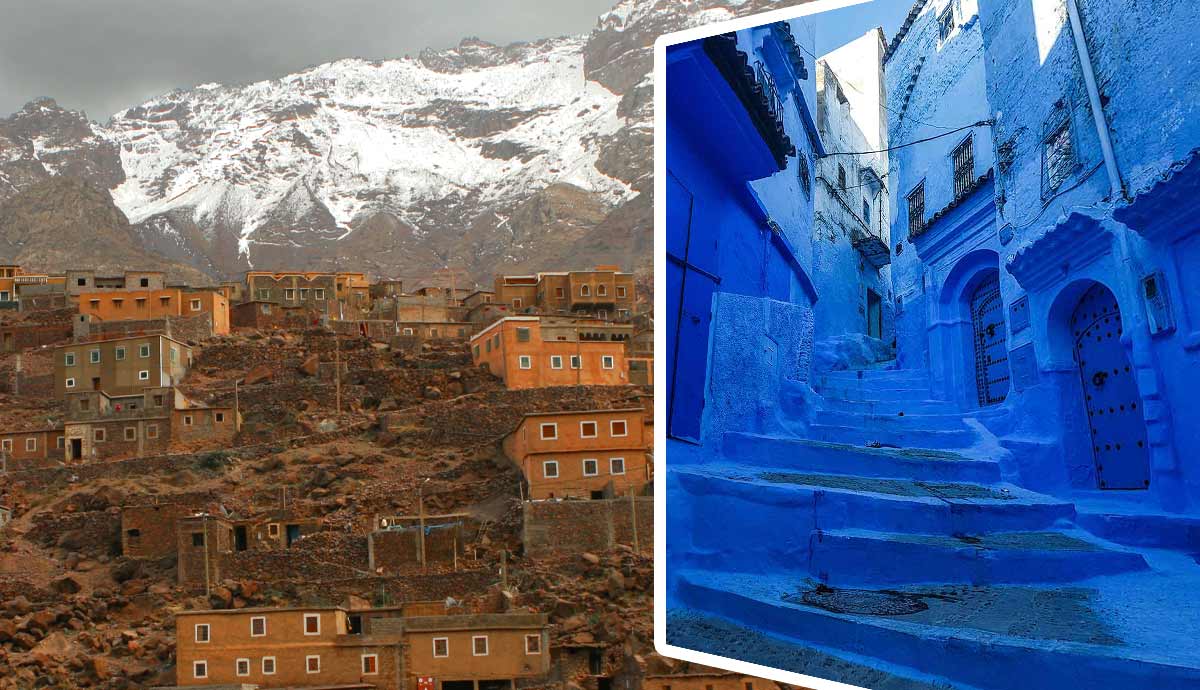

The Land of Ice That Was Never Empty

Despite the common myth of the Arctic as uninhabitable, people have lived and moved through this region for millennia. Indigenous cultures like the Inuit, Chukchi, Sámi, and Nenets built entire ways of life around seasonal migration timed not by calendars, but by the behavior of animals, the light of the sky, and the shifting ice.

Compared to the unbroken ice and brutal winds of Antarctica, the Arctic might even be called hospitable—at least by the people who’ve long known how to read its signs. Ancient travel routes here weren’t marked with signs or carved in stone, but they were no less defined. River corridors, frozen bays, ridgelines, and caribou trails formed a kind of living map, passed down through stories and shared experience. These paths allowed entire communities to move safely—often hauling sleds and supplies—across vast, changing landscapes. And when early European explorers began charting the Arctic, much of what they recorded had already been walked and known for generations, thanks to the guidance of Indigenous knowledge keepers.

Where Ice Leads the Way

In the Arctic, mobility has always been a bit of a mastered survival skill. While a frozen river might send us scurrying indoors for heat, it entices people in the far north to rejoice. Finally, they say, the roads have formed. Dog sleds have been gliding over pack ice for at least 9,000 years, linking settlements, hunting grounds, and trading posts that were isolated in the summer. The astonishing thing is that these frozen highways shift every year, so people didn’t only need to have knowledge of ancient Arctic routes; they also needed to read the ice and weather patterns to safely navigate the region.

The tools of travel were, naturally, as important as the knowledge behind them. Because knowing how, when, and where to safely cross dictated life and death. Sleds were made from driftwood lashed with sinew, carefully curved to flex with the ice. Hunters carried qulliqs (oil lamps) and wore clothes designed for sub-zero efficiency. Alongside them were dogs, domesticated for companionship but also labor and protection.

Did you know?

It is believed that the domestication of dogs for working purposes happened in the Arctic earlier than anywhere else. Some findings even suggest a distinct genetic lineage for Arctic sled dogs (like the Greenland Dog and Siberian Husky) that diverged from other dogs thousands of years ago, hinting at a long-lived, specialized history in the far north.

Today, some of these Arctic winter trails still connect remote communities in Alaska, northern Canada, and Greenland. Others lie dormant, disrupted by climate change or modern infrastructure. But traces of them survive—in stories, place names, and the deep muscle memory of those who still walk them.

Snowmobiles have made life easier in the Arctic, but only to a certain extent.

The Vast Trade Networks Beneath the Ice

Long before global trade routes stretched across oceans, Arctic peoples had their own sophisticated networks spanning thousands of miles. From Alaska to Greenland, goods like copper, obsidian, driftwood, caribou hides, and soapstone passed from hand to hand. In a landscape most would consider impassable, people were successfully sustaining some of the longest trade systems in human history.

Some archaeological finds turn old assumptions on their head, like Alaskan obsidian discovered in northern Canada, or metal tools that predate known European contact. Beads, blades, and other goods often turned up far from where they were made. But what traveled along these ancient Arctic routes wasn’t just cargo. Trade was also about relationships, so alliances, marriages, and shared ceremonies helped hold communities relatively close, even across vast distances.

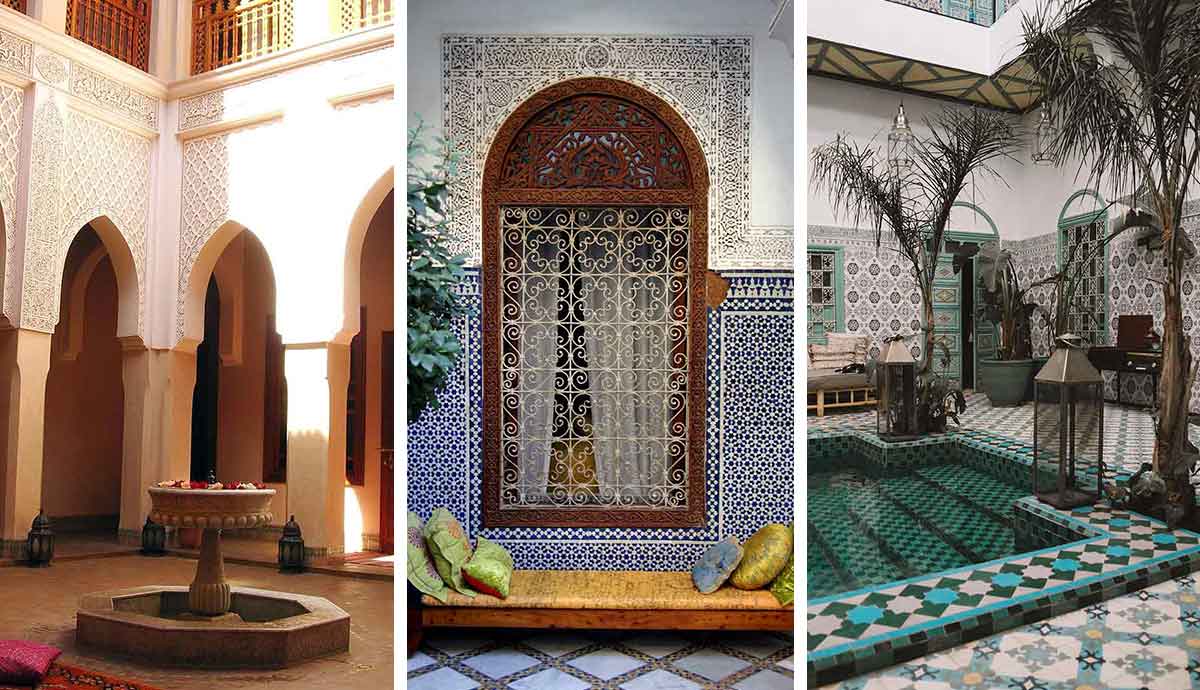

Seasonal gatherings helped maintain the networks that made life in the Arctic possible. Summer meetings in places like Nunavut and market gatherings among the Sámi in Scandinavia gave people a chance to exchange goods and information in person. These moments strengthened relationships, helped coordinate travel plans, and allowed knowledge to move between groups. In a region where conditions could shift quickly, these shared spaces offered stability.

When Outsiders Came Knocking

By the 16th century, European explorers began pressing into the Arctic, searching for the Northwest Passage and new whaling grounds. Most had little understanding of the harsh environment, and many paid the price.

Sir John Franklin’s doomed 1845 expedition is one of the best-known examples. His ships vanished while trying to navigate waters that Inuit hunters had traveled for centuries. Rescuers later discovered he’d ignored their guidance. Others, like Roald Amundsen, fared much better. He lived with Inuit families, learned to dogsled, and successfully completed the passage by applying traditional skills.

Many of the maps drawn by European powers were filled with guesswork or were distorted to suit imperial ambitions, which wasn’t unusual at the time. Meanwhile, Inuit, Chukchi, and other Indigenous groups continued navigating their territories without paper or compass, relying simply on memory, observation, and fireside storytelling.

Today, Indigenous mapping projects are reviving these routes, overlaying old knowledge on digital tools to show the Arctic as it really is: connected, inhabited, and deeply known.

Retracing Ancient Arctic Routes Today

Modern-day travelers can still follow parts of these routes, either on foot, by boat, or aboard expedition cruises that work closely with local communities. In Nunavut, guided treks explore traditional trails once used by families moving between hunting grounds. In western Greenland, you can sail past the same fjords navigated by kayak for centuries. And, on Herschel Island in the Canadian Arctic, you can walk among the remains of both Indigenous camps and 19th-century whaling outposts.

Arctic expedition cruises now often include cultural stops where Inuit hosts share stories, skills, and local perspectives. They are marvelous chances to experience the Arctic through a more historical lens, and understanding that even the most seemingly remote corners of our planet offer a long human story worth preserving.