Beneath the foundations of the legendary Spartan political system labored the oppressed Messenians. Messenia, a prosperous corner of southwestern Greece, was conquered by the Spartans in the 8th century BCE. Its population, along with elements of the Spartan region of Lakonia, were transformed into slaves, known as the Helots. For centuries, the Helots did agricultural work and fed their masters, and the Spartans created their warrior elite. The Messenians endured over 300 years of occupation but remarkably survived and re-emerged as a free community, founding Messene, one of the most impressive archaeological sites in Greece today.

The Messenian Wars and the Hero Aristomenes

Messenia occupies the southwest corner of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece. Its long coastline and fertile land made it a relatively prosperous region. In the 8th century BCE, Messenia was desirable in a country hungry for land. Some newly emerging Greek city-states sought solutions by colonizing distant lands across the Mediterranean. The Spartans fed their hunger by conquering Messenia (Cartledge, 2002, 99).

The Spartan conquest of Messenia in the 8th and 7th centuries BCE took place largely outside the historical record, with most of our information recorded centuries later and filtered through layers of myth. These stories tell us of an initial 20-year-long conquest at the start of the 8th century BCE, referred to as the First Messenian War, followed by an unsuccessful rebellion and a Second Messenian War in the 7th century BCE.

While we cannot be certain of the details of these events, the second conflict involved a key figure, the Messenian hero Aristomenes. The story of Aristomenes was likely embellished in later centuries, but he was said to have led the resistance to the Spartans for years. A series of daring raids, miraculous escapes, and mountaintop sieges became key elements in the Messenian narrative and, despite their eventual defeat, created a hero for the Messenians to later cling to.

Aristomenes’ heroics and the Messenians’ defiant stands at the mountains of Ithome and Eira in both wars created a legend, but by the late 7th century, Sparta was firmly in control of Messenia, making Sparta one of the richest city-states in Greece (Cartledge, 2002, 103). The Messenian Wars were transformative for both sides. To win and keep their new land and servile population, the Spartans had to become the militaristic society for which they were famed. For the Messenians, this meant the complete loss of their land and freedom.

Who Were the Helots?

For the Messenians, the consequences of the Spartan conquest were devastating as they were transformed into a servile population known as the Helots. Much is unknown about exactly how Spartan society functioned, but the Messenian formed the lowest level in a highly stratified system.

The Helots were slaves, but they were very particular types of slaves. Slavery was common in the ancient Mediterranean and came in many forms. Within the Greek world, many slaves were people brought in from the outside through war or trading and so were often isolated individuals. Helotage was unusual, though not unique, in being a collective status for a native population imposed by another Greek community.

The Messenian Helots continued to live in family units and may even have owned some property, unlike chattel slaves (Alcock, 2002, 190; Cartledge, 2002, 141). While they always greatly outnumbered the elite Spartan minority, archaeological survey data paints a picture of a sparsely populated Messenia with a population concentrated in a few settlements (Alcock, 2002, 193). The Helots’ main task was to work the land and hand over some of their produce to their Spartan overlords.

For the individual Spartans, this produce was of the utmost importance as their citizenship rights depended on them contributing to a collective mess. That contribution came from the surplus produced by the Helots (Cartledge, 2002, 140). Their importance meant that the Spartan state regulated the Helots, though whether the Helots were considered state or private property is disputed. A Spartan could not sell their Helots beyond Messenia, nor were they allowed to free them. Only the Spartan state could free a Helot, which they sometimes did as a reward for military service.

By remaining in their country and maintaining a family and perhaps some property, the condition of the Helot was in some ways less severe than other forms of slavery. However, there can be little doubt that this was a form of oppression and exploitation maintained through systematic brutality. The Spartan state viewed itself as perpetually at war with the Helots and formally declared war on them yearly (Cartledge, 2002, 142). A notorious practice was that of the krypteia. The krypteia was a band of young Spartans that patrolled the countryside and were allowed, or encouraged, to kill Helots. The mass murder of Helots was also not unknown. Thucydides records a case during the Peloponnesian War (4.3.2). Fearing a Helot revolt, the Spartans asked for 2,000 of the best volunteers and quietly killed them all when they came forward.

Spartan oppression was so complete that in the late 5th century, the historian Thucydides referred to the country as the land that used to be Messenia (4.3.2). However, the Messenians had not disappeared as a people, and they took every opportunity to remind the Spartans and themselves that they continued to exist.

The Messenians Fight Back

When the opportunity arose, even with Sparta at the height of its power, the Messenians were capable of large-scale resistance.

In 464 BCE, a massive earthquake struck Lakonia, reducing the towns to rubble and killing thousands. The Spartans narrowly avoided being overrun by the Lakonian Helots before the rebellion spread to Messenia. Recovering from the initial disaster, the Spartans fought back but could not overcome the Messenian rebels who gathered around a stronghold used during the Messenian Wars, Mount Ithome in southern Messenia. With the Spartans lacking the knowledge of sieges necessary to take the stronghold, the rebels held out for years. Ultimately, the Spartans were compelled to allow the Messenian rebels to leave the country safely.

The revolt following the earthquake failed to free Messenia, but it had important consequences. First, it triggered a split between the Spartans and the Athenians, which became a long series of wars. Second, the Athenians, now hostile to Sparta, settled the Messenian refugees at Naupaktos in central Greece. This created a group of Messenian exiles who played a significant role in the Messenian story.

The Messenian exiles in Naupaktos maintained their sense of Messenian identity, and when the great Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE) pitted the Spartans against the Athenians, the exiles were ready to take the fight to Sparta. In 425 BCE, the Athenians landed around Pylos in Spartan-occupied Messenia. When the Spartans took the small offshore island of Sphacteria to evict the Athenians, they committed a critical error. The Athenian navy blockaded the island, and suddenly, dozens of Sparta’s increasingly small number of citizen soldiers were trapped. When the Athenians landed troops to capture the Spartans, a Messenian contingent from Naupaktos took a leading role. The Messenians found a way around the Spartan position, completing their encirclement. The Spartans were still basking in the glory of the heroic last stand at Thermopylae in 480 BCE, but now, surrounded on all sides, they laid down their arms and surrendered. According to Thucydides (4.40), the surrender of the invincible Spartans was a shocking event at the time. We can only imagine the pride the Messenians felt in having played a major role in bringing about this humiliation.

The Athenians allowed the Messenian exiles to base themselves at Pylos, from where they conducted a damaging guerilla campaign against the Spartans. With their knowledge of the land and the local dialect, the Messenians even raided Lakonia (Thucydides, 4.41.2). Unfortunately the Naupaktian Messenians were ultimately on the losing side of the war. When the Spartans and their allies overpowered the Athenians the Naupaktian Messenians were driven further into exile. Some were said to have fled to Sicily and as far away as Libya (Pausanias.4.26.2).

Messenian Liberation

A generation later, prophesies and omens circulated among the Messenian exiles around the Mediterranean (Pausanias, 4.26.3). These were soon followed by the news that, in 371 BCE, the Spartans had suffered a catastrophic defeat at the hands of the Thebans at the battle of Leuktra. A year later, the Theban general Epaminondas marched a large army into the Peloponnese.

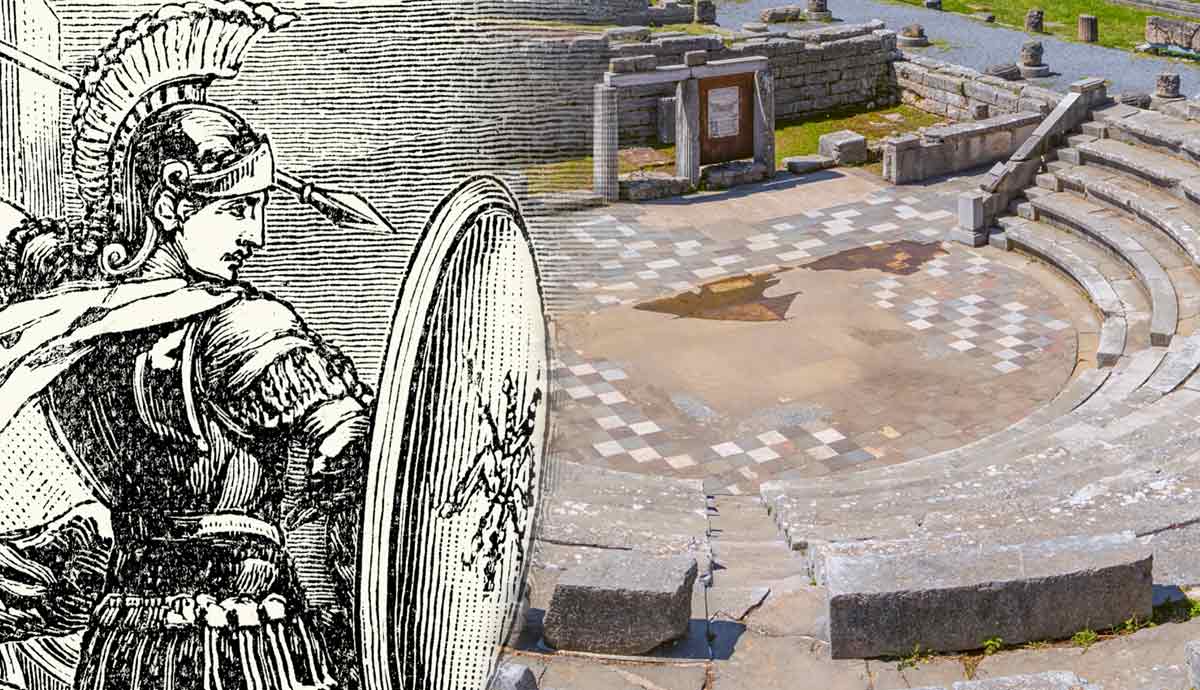

The Messenians may already have revolted from their masters (Cartledge, 2002, 254). At the very least, our sources do not mention that Epaminondas had to fight for Messenia. To permanently weaken Sparta, a decision was made to build a powerful city in Messenia. Calls went out for the scattered exiles to return, and a city was founded in 369 BCE under Mount Ithome, called either Ithome or Messene, with the latter name winning in the end (Luraghi, 2015, 287). The Messenians made it clear that they had no intention of being enslaved again as they constructed an impressive set of fortifications that enclosed 290 hectares (Luraghi, 2015, 289) and were described by Pausanias (4.31.5) half a millennium later as the strongest walls in Greece.

Almost three centuries after their conquest by the Spartans, the Messenians finally became a free community again. They had survived slavery, defeats, and exile. They were quick to remember and commemorate their long struggle and liberation. Safe behind the walls of Messene, the city was graced by statues of Epaminondas and the semi-mythical hero Aristomenes. Statues and religious practices were also brought over from Naupaktos as a reminder of that period of exile (Pausanias 4.31). With the Messenian Helots now free, Sparta’s time as the primary power in Greece was over (Cartledge, 2002, 254).

Free Messenia

Messene seems to have flourished, allowing the Messenians to take their place as one free Greek community among many. While rarely at the center of great events over the next two centuries, the Messenians participated in the ever-changing world of late Classical and Hellenistic Greece.

In the early years following liberation, the former Helots, exiles, and new citizens probably formed a single political community, which may have created a federal structure for Messenia (Lurghi, 2015, 291). The surrounding region seems to have recovered, with indications of denser settlement compared to the era of Spartan domination (Alcock, 2002, 196). The initial concern of the Messenians was safety from a Spartan revival. To that end, they worked closely with Megalopolis, another city founded in the 360s, and the eternal Spartan enemy Argos, to keep the Spartans contained (Kralli, 2017, 17). Over time, the Messenian attitude to their former tormentors eased. In 272 BCE, the Messenians came to Sparta’s aid when Pyrrhus attacked, which ushered in half a century of peace (Kralli, 2017, 125).

The Hellenistic Age brought new challenges. There was the ever-present danger of intervention by one of the great powers, Macedonia and Rome. Closer to home was the expanding federal state of the Achaians, which, by the mid-3rd century BCE, contained most of the Peloponnese. Among the states holding out were the Spartans and Messenians. We do not know enough about Messenia at this point to explore this position fully. Pausanias suggests one reason was to avoid the frequent wars between the Achaians and Spartans (4.29.6). Keeping themselves free from any potential dominating power in the Peloponnese has been identified as a long-term Messenian policy (Kralli, 2017, 326). Having been erased as a political community for so long, it is not surprising the Messenians were reluctant to compromise their autonomy by joining a federal unit.

Gradually this isolation became untenable. Messene lost control over some Messenian cities, which joined the Achaians. Finally, in 191 BCE, Messene was forced into the Achaian League. Still, the Messenians were not willing to settle for this arrangement and they revolted in 183/2 BCE. The revolt was a failure and may not have been backed by the whole of Messene, but it had an impact as the war led to the capture and execution of the great Achaian leader Philopoimen. The failed revolt was one of the last major events noted in Messenian history. Soon, the whole of Greece and the Mediterranean were swallowed up by Rome.

The Messenian story remains one of the most remarkable in Greek history. Their land occupied, the Messenians disappeared from the political map of Greece, subsumed by a seemingly unbeatable military power. However, the Messenians survived and returned to take their place in the Greek world. The walls of Messene, which largely still stand on the slopes of Mount Ithome, testify to the endurance of a seemingly defeated and dispersed people.

Bibliography

Alcock, S. (2002) “A simple case of exploitation? The Helots of Messenia” in P. Cartledge, E. Cohen, and L. Foxhall (eds.) Money, Land and Labour, pp. 185-199. Routledge.

Cartledge, P. (2002) Sparta and Lakonia: A Regional History from 1300 to 362BC. Routledge.

Kralli, I. (2017) The Hellenistic Peloponnese: Interstate Relations: A Narrative and Analytic History, 371-146 BC. The Classical Press of Wales.

Luraghi, N. (2015) “Traces of Federalism in Messenia” in Beck, H. and Funke, P. (eds.) Federalism in Greek Antiquity, pp. 285-296. Cambridge University Press.