Empires often get the credit, but it’s the quieter cultures that built the systems we still rely on. From alphabets and coinage to water management, diplomacy, navigation, and long-distance trade, these breakthroughs began in places many people overlook. Meet twelve ancient peoples whose innovations still power the present.

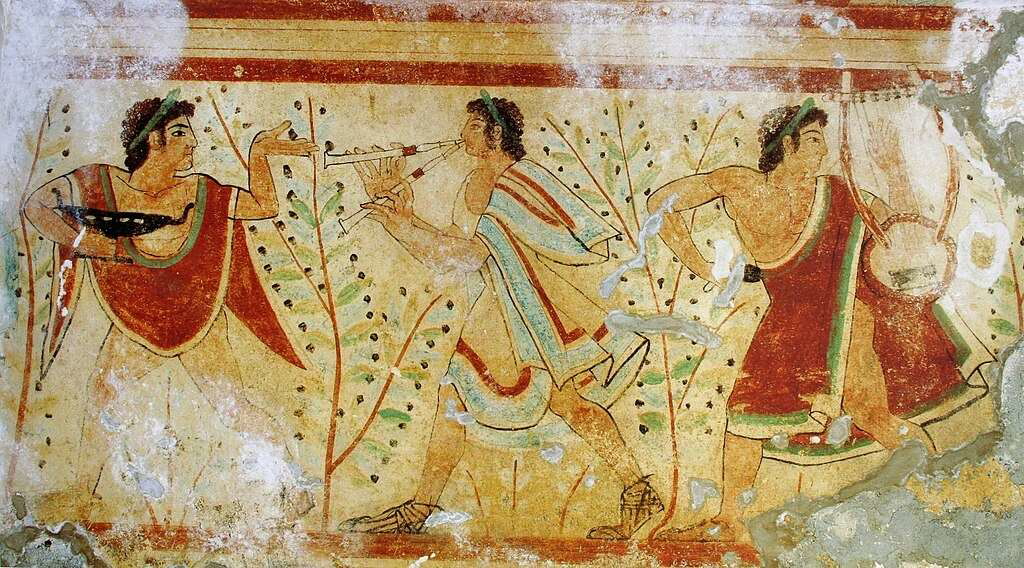

1. Etruscans

The Etruscans planned cities where ceremony, courts, and processions had a proper stage, making public life feel organized and shared. Rome adopted Etruscan forms—arches, forums, and civic ritual—and then spread that playbook across its empire. We still use the same visual language in government buildings and public squares that signal authority and community.

| Timeline | Core region | Signature innovation | Lasting impact | Hallmarks |

| 9th–3rd centuries BCE | Central Italy, Tuscany and Lazio (Etruria; Tarquinia, Cerveteri) | Urban planning, triumphal arch | Templates for Roman civic power | Ritual authority, drainage works, tomb art |

2. Sogdians

The Sogdians built a chain of caravan hubs that moved goods, letters, and stories safely across Asia. Their contracts and partner networks created dependable long-distance trade before banks and customs unions existed. Modern supply chains still run on the same idea: trust built through documents, checkpoints, and shared standards.

| Timeline | Core region | Signature innovation | Lasting impact | Hallmarks |

| 4th–10th centuries CE | Uzbekistan and Tajikistan (Samarkand, Bukhara, Panjikent) | Multilingual contract trade | Normalized long-distance exchange | Caravan hubs, letters, diaspora nodes |

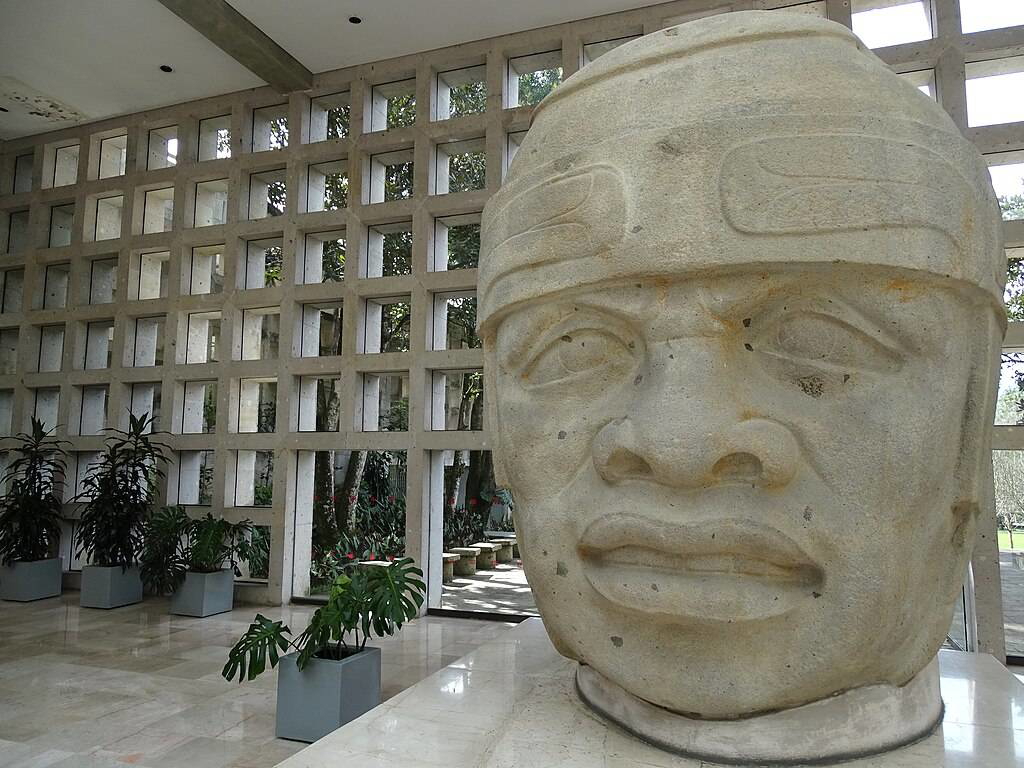

3. Olmecs

The Olmecs combined rulers, rituals, and sports in plazas, where people witnessed power and celebration in the same place. That setup became the model for later Mesoamerican capitals and public festivals. Today’s stadium districts and civic squares echo this formula by uniting identity, spectacle, and city life.

| Timeline | Core region | Signature innovation | Lasting impact | Hallmarks |

| 13th–5th centuries BCE | Gulf Coast of Mexico, Veracruz and Tabasco (San Lorenzo, La Venta) | Colossal heads, ritual centers, ballgame | Templates for Maya, Zapotec, and Aztec | Basalt heads, jade, jaguar motifs |

4. Scythians

The Scythians showed that fast riders with accurate bows could outmaneuver heavier armies. Neighbors copied their tactics and even their riding trousers to keep up on the steppe. Modern strategy still prizes mobility and rapid response, whether on horses, wheels, or aircraft.

| Timeline | Core region | Signature innovation | Lasting impact | Hallmarks |

| 9th–2nd centuries BCE | Ukraine, southern Russia, and the Kazakhstan steppe (Pontic and Eurasian steppe) | Mounted archery, riding trousers | Rewrote warfare and mobility | Kurgans, gold stags, felt textiles |

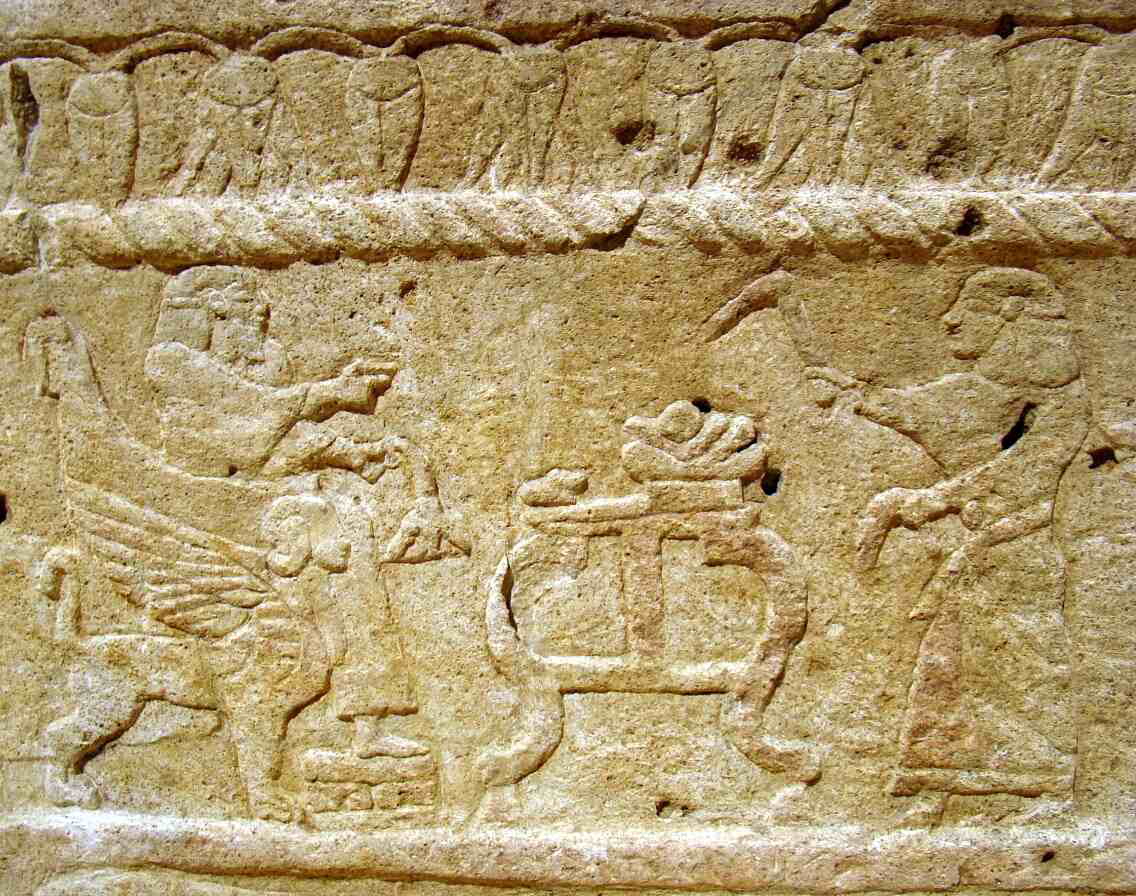

5. Hittites

The Hittites wrote laws and treaties, so rules were clear and obligations could be checked later. Their archives transformed diplomacy into a repeatable process, rather than a personal promise. International agreements still follow this method, using written terms to manage conflict and cooperation.

| Timeline | Core region | Signature innovation | Lasting impact | Hallmarks |

| 16th–12th centuries BCE | Central Türkiye, Anatolian plateau (Hattusa, Boğazkale) | Treaty of Kadesh, law codes | Frameworks for treaties and extradition | Cuneiform tablets, lion gates, archives |

6. Nabataeans

The Nabataeans captured rare desert rain, stored it in cisterns, and released it when needed so cities like Petra could thrive. Reliable water made long-distance trade and urban life possible in a dry climate. Modern water planning in arid regions uses the same logic of capture, storage, and controlled flow.

| Timeline | Core region | Signature innovation | Lasting impact | Hallmarks |

| 4th century BCE–2nd century CE | Southern Jordan and northwest Saudi Arabia (Petra, Wadi Rum) | Cisterns, channels, ceramic pipelines | Urban water security in arid zones | Rock-cut facades, channel cuttings, basins |

7. Phoenicians

The Phoenicians trimmed writing to a small alphabet of sounds that ordinary people could learn quickly. This change sped up record-keeping and facilitated the exchange of ideas and trade across the sea. Many scripts used today descend from that alphabet, which still makes reading and writing faster.

| Timeline | Core region | Signature innovation | Lasting impact | Hallmarks |

| 15th–4th centuries BCE | Lebanon and the Levant coast (Tyre, Sidon, Byblos) | 22-sign phonetic alphabet, colonies | Seeded Greek and Latin scripts | Purple dye, glass, cedar trade |

8. Aramaeans

The Aramaeans promoted a practical language and script that different kingdoms used for courts, markets, and mail. This shared paperwork allowed rival states to cooperate without having to share the same rulers. Modern lingua francas and standardized forms work the same way, keeping complex systems running.

| Timeline | Core region | Signature innovation | Lasting impact | Hallmarks |

| 11th–6th centuries BCE | Syria and northern Iraq (Damascus region, upper Mesopotamia) | Aramaic administration, adaptable script | Lingua franca across empires | Bilingual stelae, papyri, seals |

9. Lydians

The Lydians minted stamped coins that carried a promise of value strangers could trust at a glance. Prices, wages, and taxes became easier to set because money was standardized. Our economies still depend on that principle, whether the unit is a coin, a bill, or a digital balance.

| Timeline | Core region | Signature innovation | Lasting impact | Hallmarks |

| 7th–6th centuries BCE | Western Türkiye, Aegean interior (Sardis, Manisa province) | Stamped electrum coinage | Standardized money for markets and taxes | Lion punch marks, bimetal issues, weights |

10. Nok Culture

The Nok culture utilized iron tools to clear land, accelerate farming, and construct buildings, thereby supporting the growth of towns. At the same time, Nok terracotta heads showed community identity and skilled craftsmanship. Modern agriculture and construction follow the same pattern: better tools reshape work and landscapes.

| Timeline | Core region | Signature innovation | Lasting impact | Hallmarks |

| 15th–3rd centuries BCE | Central Nigeria, Jos Plateau, and Kaduna region | Independent iron metallurgy | Iron tools boosted farming and growth | Terracotta heads, tubular eyes, furnaces |

11. Sabaeans

The Sabaeans built dams and canals that protected fields and then shipped frankincense and myrrh along long trade routes. Strong infrastructure paid for high-value exports, which in turn funded more building at home. Regions continue to grow in this manner today, connecting reliable resources to the goods the world desires.

| Timeline | Core region | Signature innovation | Lasting impact | Hallmarks |

| 8th century BCE–3rd century CE | Yemen, Ma’rib oasis and highlands (Saba heartland) | Marib Dam, incense economy | Desert agriculture and luxury logistics | Sabean script, temple precincts, dams |

12. Lapita Culture

The Lapita culture taught sailors to read stars, swells, and birds so the open ocean became a mapped route. Their dentate-stamped pottery, often lime-infilled and shared across far islands, traces those routes and shows how ideas and families moved together. This combination of wayfinding and portable craft remains a model when technology fails and proves that knowledge can be stored in practice and in objects.

| Timeline | Core region | Signature innovation | Lasting impact | Hallmarks |

| 16th–5th centuries BCE | Melanesia to western Polynesia (Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji, Tonga, Samoa) | Non-instrument navigation | Foundations of Polynesian societies | Dentate-stamped ceramics, outrigger craft |