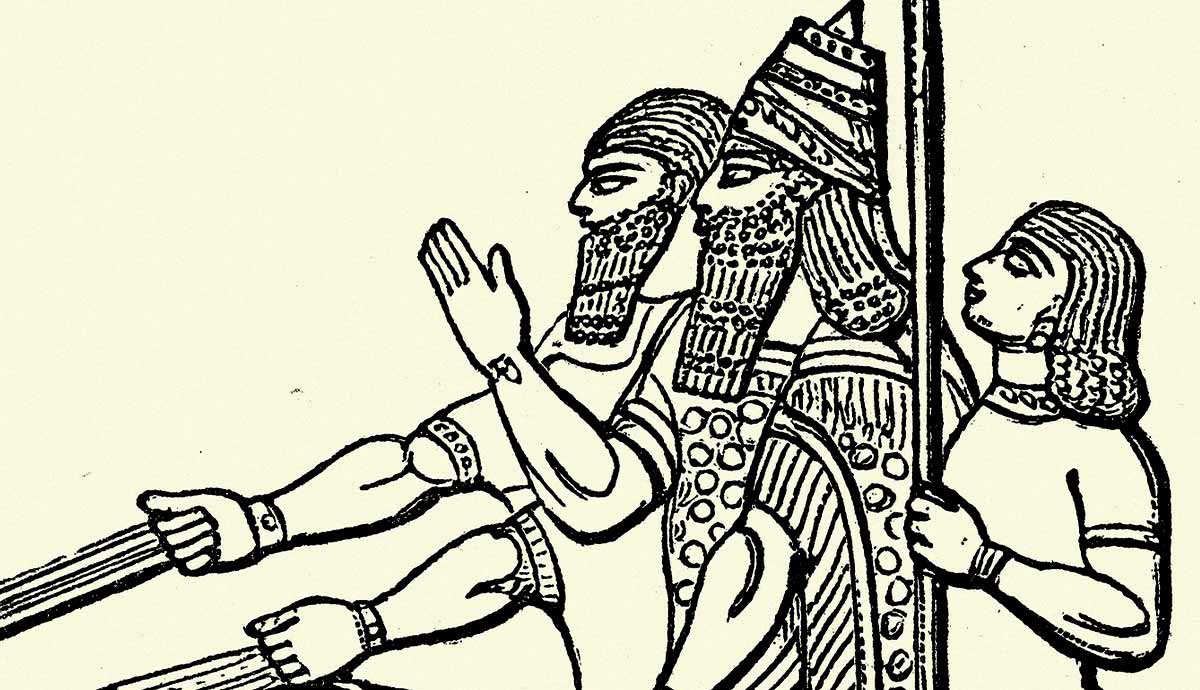

Over a thousand years of Assyrian history, the city-state turned empire conquered many settlements and kingdoms. Their success compared to other contemporary states was largely due to their decisive and brutal approach to suppressing those they defeated. Assyrian monarchs utilized a variety of strategies that could be considered torture, which they celebrated in dramatic fashion in their annals and wall reliefs.

1. Treatment of Fallen Enemies

After the Assyrians fought enemy armies, they routinely tortured the survivors. Ashurnasirpal II proudly stated that he “flayed as many magnates as had rebelled against him” and draped their skins over a pile of dead bodies as well as hanging some on stakes. Such behavior was commonplace and many other kings recorded similar actions such as Shalmaneser III, Tiglath-Pileser III, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanipal.

The precedent for tormenting prisoners was firmly set by the start of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and began escalating in intensity from the reign of Ashurnasirpal II and particularly under the Sargonid kings. Further violence was implemented to put off other potential rebels who might resist Assyrian control. Common features of Assyrian torture after a battle included the piling of deceased bodies, the impalement of bodies, the displaying of severed heads, amputating body parts of those still alive, and other forms of permanent disfigurement such as the gouging of eyes.

Civilians were increasingly targeted by later kings and bodies were often buried in mass graves in the neighboring countryside. Under Sargon II prisoners had their lips pierced and were tethered via the piercing. Sennacherib brought in a particularly horrific form of abuse whereby prisoners had their testicles cut off and what remained was twisted or even pulled until their insides came out. In addition to the living or even recently deceased, Ashurbanipal persecuted the long-dead ancestors of the Elamites. The Assyrian ruler desecrated the graves of Elamite kings and brought their bones back to Assyria as plunder.

2. Taking of Hostages

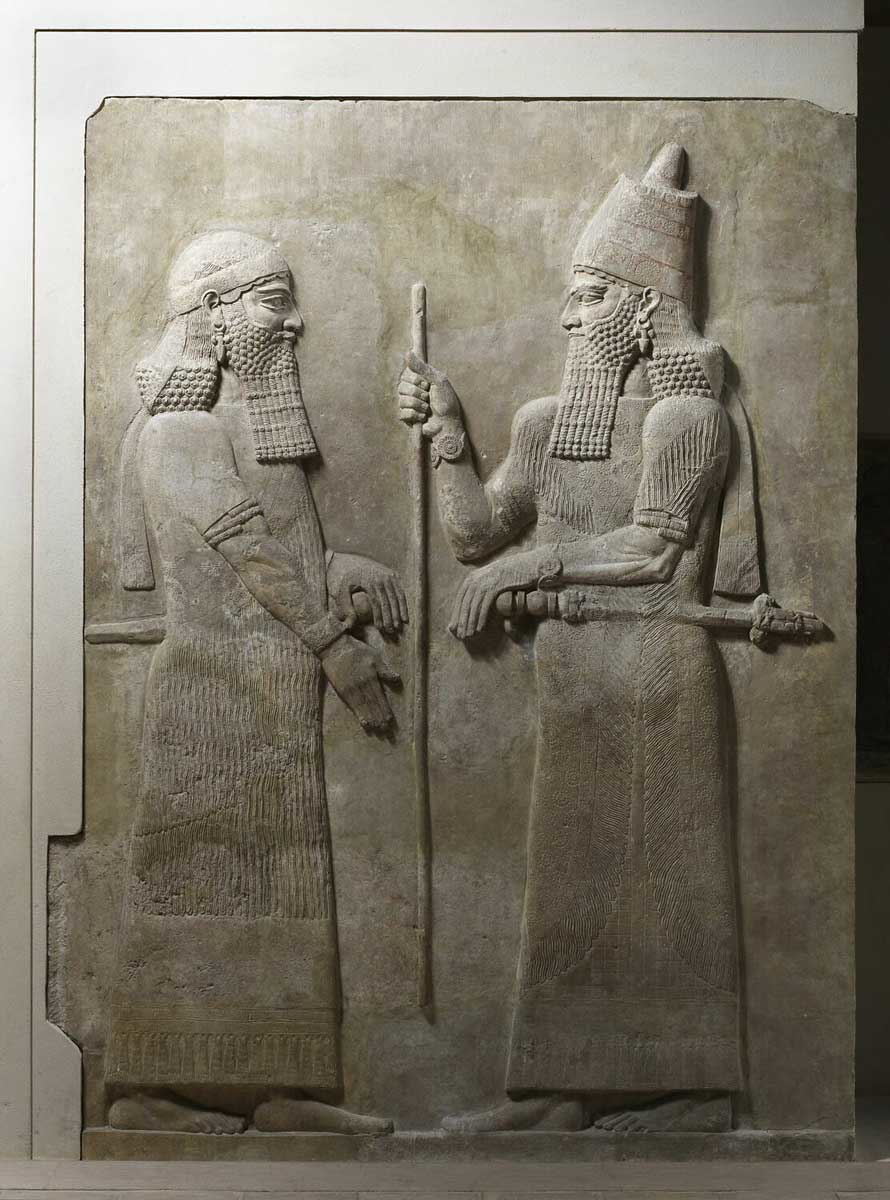

Many of those left alive after the onslaught of battle were taken back to Assyria as captives, which was practiced by many kingdoms in the ancient Near East. This was a tactical decision and hostages were used to strengthen the Assyrian state in a variety of ways. The Assyrian word for hostage was līţu and Ashurnasirpal II even titled himself şābit līţu which translates to “Conqueror of the Hostages.” Subsequently, this title was assumed by many of his successors.

Elites and members of the upper class of society could be used as leverage when establishing treaties in favor of Assyria with potential enemies. In many cases, the subordinate state would send Assyria hostages as part of treaties, who would act as insurance and project a sense of goodwill between the kingdoms. Many of the sons of other kings were raised at the Assyrian court, not only giving the Assyrian leverage, but they raised the princes, who would be kings, to favor Assyria.

The daughters of kings were also occasionally sent to the Assyrian palace to become concubines or wives. Again, this initiated strong connections between various royal families, ensured loyalty from those conquered by Assyria and even brought in money to Assyria as they came with dowries.

In these specific cases, the hostages were treated well, but ultimately were still taken from their homelands with the potential to be made a spectacle of and killed if their families upset the Assyrian king. The same treatment cannot be seen in the lower class population as they were deported to wherever the empire needed them most.

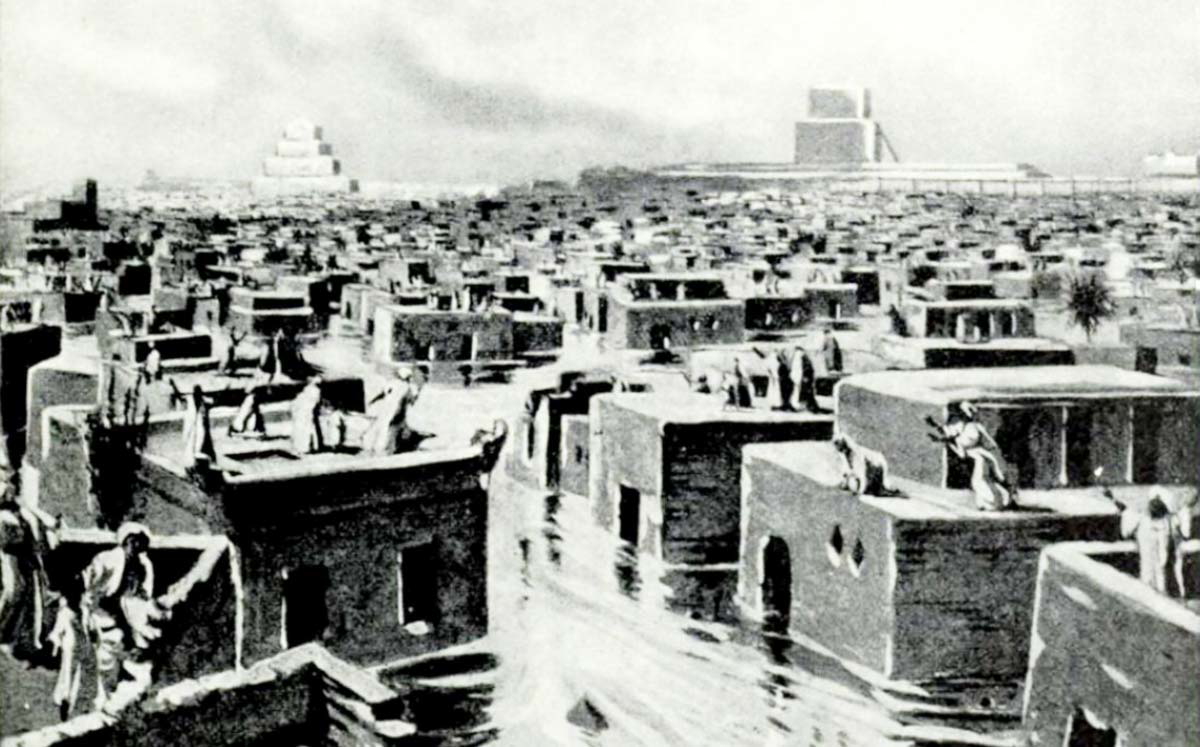

3. Mass Deportations

Prisoners from conquered lands were brought back to Assyria to ensure the increasingly larger state could effectively control its empire. For example, some surviving soldiers were incorporated into the Assyrian army. They were employed in the most strenuous work such as construction or farming. If people had a trade, they could be forced to use their skill in service of their conquerors.

The deportations aimed at causing the complete upheaval of entire populations. They were settled in areas that could have totally new climates, food, and even diseases, often in desolate places where the farming they were sent to do was near impossible. Additionally, these new inhabitants were afforded very little in terms of housing. While families could stay together, they were often fed just grain while they were forced to work long days in the fields.

Furthermore, these new settlements were weakened as artisans, workmen, and other citizens of higher education had been removed, undermining social structures, which meant that they were far less likely to resist Assyrian rule.

As well as the physical limitations of an uprising, there was also a lack of morale caused by their complete separation from their homes and old lives. Likewise, in ancient Mesopotamia, religion was heavily linked to location. Therefore, another tenet of torture manifested in the fact that these groups were hundreds of miles from their gods. At a time when religion and active worship of deities were such an integral part of everyday life, this must have been a devastating blow to those who had quite literally lost everything.

The “Assyrian Exile” or the “Assyrian Captivity” was perhaps the largest deportation, which saw the Israelites deported en masse. The Assyrian Captivity was mostly at the hands of Tiglath-Pileser III, Shalmaneser V, and Sargon II, although many Assyrian rulers fought with and subjugated Israel. Towards the end of Shalmaneser V’s reign, Israel rebelled against Assyria and a three-year war ensued. The Assyrian response was initiated by Shalmaneser V and finished by his successor, Sargon II, who claimed to have deported over 27,000 Israelites.

The Second Book of Kings in the Bible describes how Assyria came to Israel and cast out many Israelites and also moved other groups of people into Israel. 2 Kings 17 explains that the people of Israel had been practicing religion in a way that displeased the gods with idol worship and other customs that their God had banished from the land. Moreover, in Hosea 13:16, it is said that the Assyrians killed children and “ripped open” pregnant women. It is not certain whether this was meant literally or figuratively, but there are records of the Assyrians perpetrating similar actions in Elam.

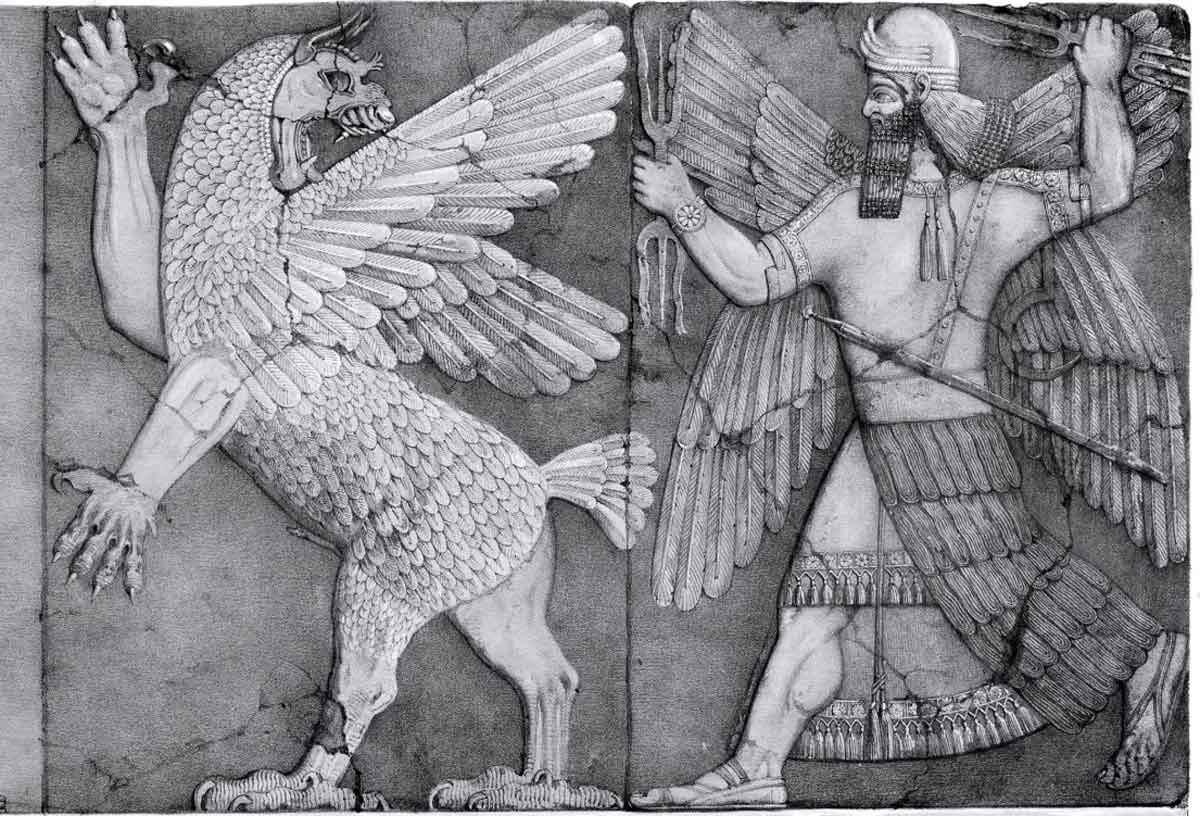

4. Religious and Ideological Warfare

Religious violence in the ancient Near East was complicated and often frowned upon by the Assyrians, a notable example being the decimation of Babylon and its religious sanctuaries at the hands of Sennacherib. However, with smaller kingdoms, local deities were frequently mistreated to destroy morale in the hopes this would prevent further revolts. Furthermore, if the Assyrians were able to wreak havoc on a settlement or population, the inhabitants would often conclude that their gods had abandoned them.

However, in many respects, Assyria was deferential to many religions. Most civilizations believed in a polytheistic structure of deities and therefore that the native gods of other cultures did exist and in a way interacted with each other. When a subjugated state broke a treaty, the Assyrians would invoke deities from both sides to punish them.

Idol worship was a common practice as part of many of the varied religious systems across contemporary Mesopotamia and could be utilized in warfare. The term “godnapping” is often used by historians, which refers to the practice of taking the statues of gods from defeated states back to the homeland of the victorious forces. It was common belief that some part of the deity lived in their idols and so if their idols were taken, the remaining inhabitants had lost their safety and security.

In Shalmaneser III’s Black Obelisk inscription, he describes how he “uprooted” the king’s sons, daughters, and gods and brought them back to Assyria. Likewise, this practice was certainly intended to shame, embarrass, and provide the ultimate insult to the conquered civilizations. In addition, this would deprive the gods of important rituals that were performed to honor them and further separate the people from cosmic protection.

Worse still than kidnapping was the complete destruction of religious idols. This was far less common due to a general fear of offending the gods, but was enacted from time to time. Sargon II employed this terror tactic and stated that it was to guarantee Assur’s ultimate power across the ancient Near East, by which he implied the supremacy of Assyria.

Sennacherib’s treatment of Babylon is the most notable example of the destruction of deities. Incredibly, Sennacherib recreated the ancient flood myth when he destroyed Babylon and all its religious sites by cutting new pathways for the Euphrates so that it swept away the urban area of the city.

Sennacherib’s devastation of Babylon caused significant unrest in Assyria, prompting the king to defend his actions through a myth in which the chief Assyrian deity, Assur, put Marduk on trial. He further disrespected Babylon by proclaiming that Assur had replaced Marduk as the central figure of the Babylonian New Year festivities, likening Babylon to the chaotic goddess Tiamat, and associating himself with Marduk.

Might and Divine Right

Assyria’s constant and at many times unwavering success would have illustrated to people across Mesopotamia that Assyria was blessed by the gods and was fully supported by powerful cosmic forces. An enormous part of the structure of Assyrian beliefs was the duty of the king to expand territory on behalf of the gods, a divine instruction that ensured legendary kingship. Consequently, this message of absolute celestial power worked to spread fear and also manifested in a war against other gods on occasion.