America’s pre-independence history is sprinkled with glimpses of the ideas that would lead to revolutionary sentiment and, eventually, the outbreak of war. One such stirring was Bacon’s Rebellion in colonial Virginia. However, hindsight and research have brought new questions to these events in the years since. Was the rebellion a measure to seek equality in the New World? Or was it a power struggle between small groups of men? Regardless of its causes, the revolt had implications for the new government, local Indigenous peoples, African Americans, and the economy.

What Was Bacon’s Rebellion?

Nathaniel Bacon arrived in the Virginia Colony with his wife in 1674. Only two years later, he found himself embroiled in a rebellion that carried his name. Bacon was an educated, relatively wealthy farmer who became part of the governor’s council, one of the earliest colonial governmental entities. The council consisted of around a dozen wealthy Virginians who advised the colonial governor, who answered to the king, about governmental matters. Together with the governor, the council made up the highest court in the colony. In addition, Bacon was a cousin by marriage to Governor William Berkeley. Bacon was welcomed by his cousin upon his arrival in Virginia, but their relationship soon took a turn.

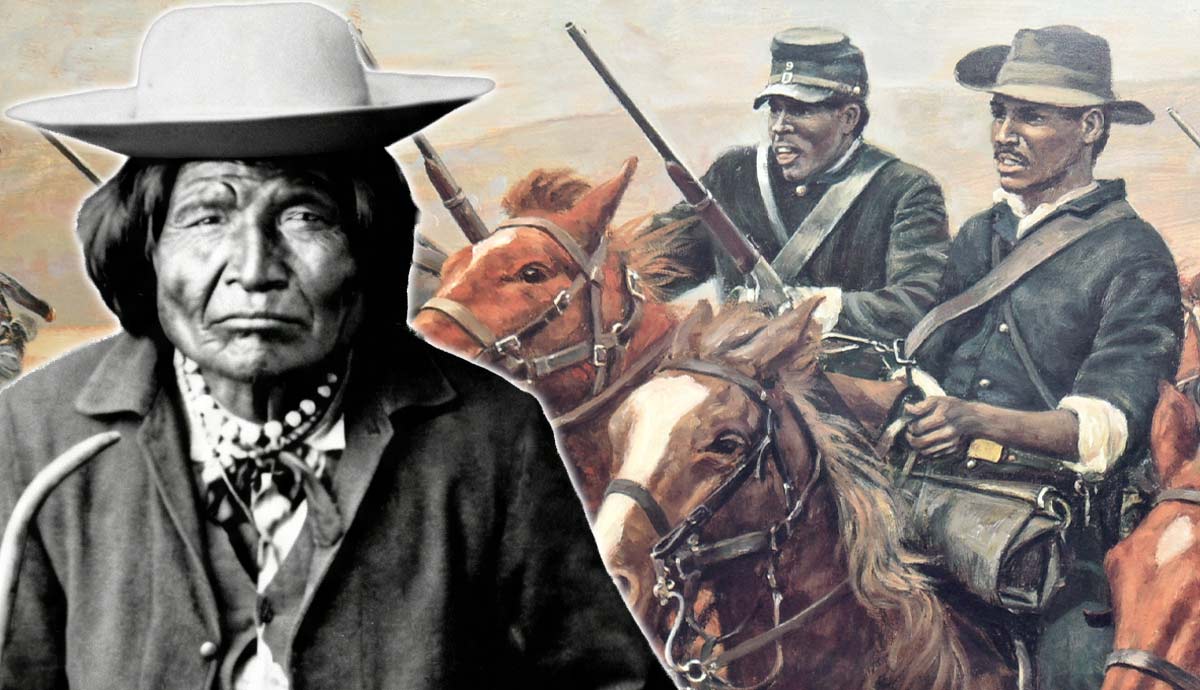

A series of problems and unfortunate events led to general unrest among the Virginia colonists in 1676. Searching for a scapegoat, they found one in the local Indigenous population. A trading dispute between colonist Thomas Mathews and members of the local Doeg tribe resulted in bloodshed and was soon followed by a retaliatory attack by a militia made up of Virginia colonists. However, the retaliation was exacted upon a different tribe, the Susquehannocks. Thus, skirmishes and raids between the colonists and Native groups followed as each side attempted to exact revenge.

Berkeley tried to find a compromise. He wanted to keep peace with Native tribes while satisfying the colonists, but it seemed he was unable to do both. He attempted to collect weapons from local tribes while setting up a defensive zone around the colony. Wanting to preserve trade with “friendly Indians,” he allowed business of that nature to continue as usual under government supervision, angering the already tense colonists, including Bacon, who had been elected de facto leader of those wishing to drive the tribes out of Virginia permanently. Bacon accused Berkeley of favoring his rich merchant friends and continued attacking Indigenous settlements. Berkeley declared Bacon a rebel and removed him from the council, ordering him to Jamestown for a trial. Bacon fled and continued attacking tribes, including the Pamunkey and Occaneechee people, who had friendly relationships with the colony.

Despite his removal from the council, Bacon was elected to the House of Burgesses, the first democratically elected legislative body in what would become the United States. Though he arrived in Jamestown for the political session with a militia in tow, he was arrested. The traditional punishment for treason at the time was death, but Berkeley pardoned Bacon and reinstated him to the assembly once he apologized.

Bacon stormed out of the assembly in the middle of a heated debate about how to deal with the Indigenous people and surrounded the statehouse with his militia force. Finally, Berkeley gave Bacon free rein to deal with the “Indian Problems” as he saw fit, essentially handing Bacon power over Jamestown. On July 30, 1676, Bacon issued “The Declaration of the People,” denouncing Berkeley and the government. In the meantime, Berkeley was working to infiltrate the rebellion and gain back his power. Violence broke out, and on September 19, Bacon’s men burned Jamestown to the ground.

Who Was Involved in Bacon’s Rebellion?

While in some historical sources, Bacon’s Rebellion is framed as the result of frustrations of Virginia’s frontier colonists coming to a head, others argue that it was a simple power struggle between two prominent men: Nathaniel Bacon and William Berkeley. Both men were stubborn and showed a desire to protect selfish interests. Nathaniel Bacon was educated and intelligent but known as a troublemaker. In fact, his father had sent Bacon to Virginia in an effort to keep him out of trouble in England after he attempted to swindle a neighbor. Still, the charismatic Bacon knew how to gather support and quickly positioned himself as a leader in the rebellion that bore his name.

Bacon’s popularity was due in part to his zero-tolerance attitude toward local Indigenous people. This attitude granted him the backing of many wealthy landowners living on Virginia’s frontier who were struggling to grow and maintain their properties, which overlapped with Native people’s homelands. In addition, Bacon earned the support of the area’s poor, including indentured servants and African-American slaves, promising freedom in exchange for service in his militia. For the first time in the colonies, Black and white people were officially united under a common cause. Later, Thomas Jefferson framed Bacon as a patriot, resulting in a positive interpretation of the rebel for a time.

On the other hand, William Berkeley was older and a veteran of the English Civil War. He was favored among the landed gentry and in the good graces of the king. In the end, he was the longest-serving governor in Virginia’s history. However, as problems in his colony escalated, he fell out of favor with many, and whispers of corruption circulated.

What Were the Causes of Bacon’s Rebellion?

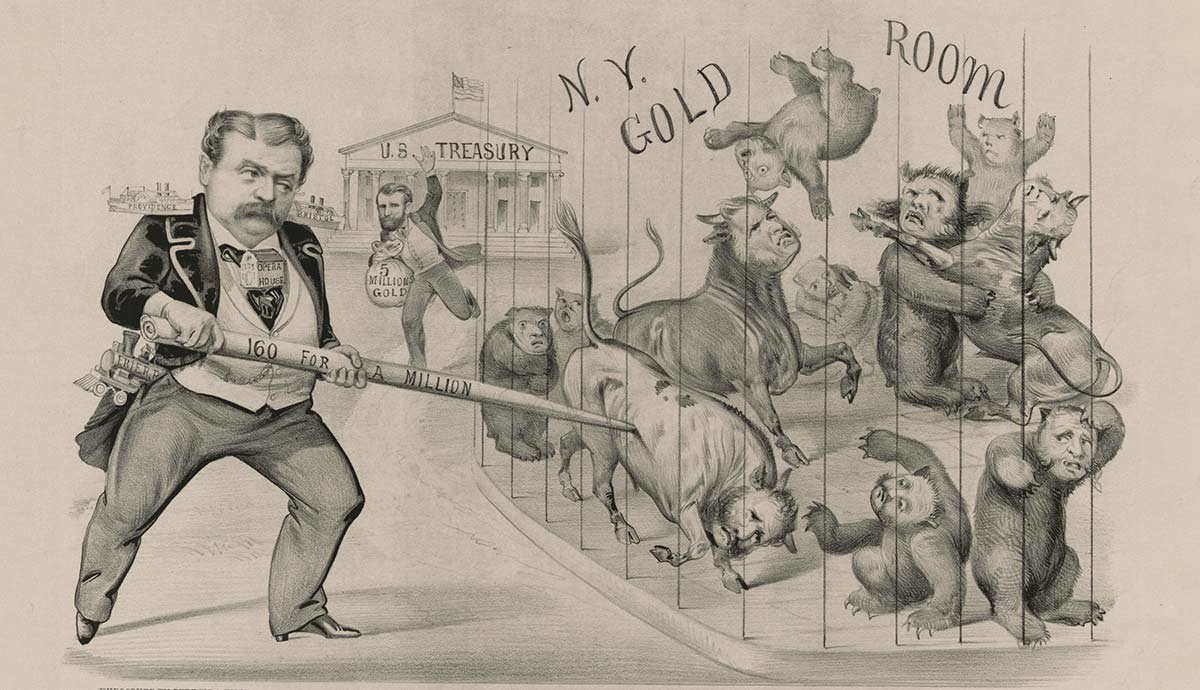

Problems that were compounding and increasing in number contributed to Bacon’s success in gathering support for his rebellion. Tobacco was the main crop for the colony at the time, and prices had taken a hit in recent years. The monoculture nature of the agricultural market made it vulnerable to fluctuations, and growing colonies in Maryland and the Carolinas added to the loss of profits. Freed indentured servants were frustrated with their poor economic opportunities upon finishing their contracts, and higher levels of taxation angered all classes. Political participation was limited to those who owned land, and politicians like the governor commonly played favorites.

The tension and stress that resulted from these problems gave the colonists the opportunity many had been seeking to go to battle against Virginia’s Indigenous people, removing the original inhabitants from lands they now perceived as theirs. When Berkeley did not support these measures in an effort to maintain favorable trade, the rebellion had the fuel it needed to burn. Even when the government relented and allowed for measures against hostile Natives to be taken, the taxes they foisted on the colonists to pay for such action only added to the blaze. The quarrel between Mathew and the Doeg happened at the perfect time for the rebellion to erupt.

How Was Bacon’s Rebellion Resolved?

Bacon’s Rebellion ended abruptly. On October 26, 1676, Nathaniel Bacon died suddenly as a result of dysentery. The next day, King Charles II of England issued a proclamation to halt the rebellion, sending not only military support but an investigative body to the colony. Berkeley regained control of Jamestown, hanging 23 participants in the rebellion. However, the investigation found that Berkeley used excessive harshness in administering these punishments rather than due process. He was also accused of seizing personal property for self-enrichment in the aftermath. He was removed as governor and headed to England to defend himself. However, he died before he was able to deliver his version of the story to the king. The colony continued much as it had before the rebellion, with the planter class retaining power and social inequalities remaining prominent.

What Is the Legacy of Bacon’s Rebellion Today?

Though it ended suddenly, the ideas brought forth by Bacon’s Rebellion impacted the future of Virginia. As the 17th century drew to a close, the number of enslaved people in the colonies was rapidly rising. While Bacon had campaigned for a number of freedoms for the citizens of Virginia, these changes wouldn’t apply to the growing Black population. Bacon had shown that Black and white people could unite in a cause and be somewhat successful. This threatened the status quo and encouraged the racial divide in the growing country as the upper class worked to preserve their comfortable status. As more slaves poured into the colony, comparably fewer new white settlers arrived, highlighting the racial differences. Bacon’s determined doggedness to destroy the American Indian would be another disturbing continuance of the rebellion, eventually escalating into the idea of Manifest Destiny throughout America.

Whether Nathaniel Bacon’s intentions included a desire for freedoms and better conditions for all or were strictly a racist tirade against Indigenous people is a point of contention, but the results are the same. Bacon helped usher in a new era that would mark the development, including both positive and negative aspects, of not just Virginia but the colonies and the future United States.