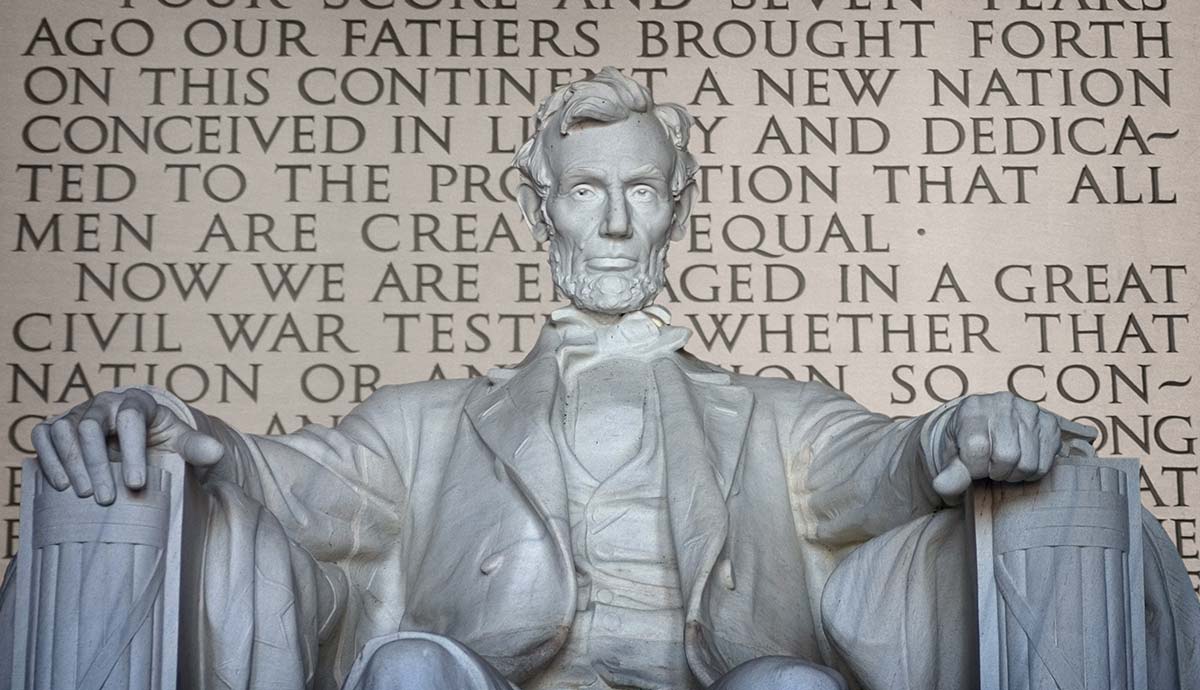

For many nations, significant moments in history are forged in the heat of battle and the bloody outcome of such events. For England, the Battle of Hastings is often thought of as the defining moment that birthed the nation, but this is quite inaccurate. England was born before the Normans wet their toes in the English Channel and decided to sail across to the fair isles of Britain.

More than a century before they fought the Anglo-Saxons, the latter had already forged the nation of England, defeating many of their enemies at Brunanburh, leading to victory and great prestige for King Æthelstan, who united the fractured English kingdoms.

The Foundation for England’s Unification

In the 9th century, England played host to a number of political entities. By 871 CE, at the start of King Alfred’s reign, much of England had been conquered by the Vikings, who had invaded with the Great Heathen Army in 865. They defeated the Northumbrians, installing a puppet ruler immediately after killing the Northumbrian kings, Osberht and Ælla. The southern part of Northumbria became the Kingdom of York, under direct Viking control. The Vikings also conquered East Anglia, killing King Edmund, who became known as King Edmund the Martyr for his refusal to convert to paganism and his execution by the Vikings, potentially led by Ivar the Boneless, a son of Ragnar Lodbrok.

Mercia was greatly weakened by the Vikings on its eastern border, and only Wessex stood any real chance against the Viking threat. Alfred of Wessex was an effective king, and ruled from 871 to 899, as King of the West Saxons, and then as a unifying force, the King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886.

Several years after defeating the Vikings at Edington in 878, Alfred unified Wessex and Mercia by marrying his daughter Æthelflæd to Æthelred, the Mercian ruler, in an agreement that made Alfred effectively the suzerain of Mercia. This was the first political step towards a unified England. Throughout his reign, Alfred consolidated the power of the Anglo-Saxons, and his son, Edward the Elder, continued his father’s legacy. Under his rule, a West Saxon and Mercian army dealt a crushing blow to an invading Northumbrian army in 910, reducing the threat from the Vikings to the north. With the help of his sister, Æthelflæd, who ruled Mercia after her husband’s death, Edward liberated southern England from the Vikings in the years that followed.

The process of unification wasn’t a straightforward event with no obstacles, however. At the end of Edward’s reign, there was growing discontent among the Mercians over Wessex rule. Edward had exercised direct control over Mercia after his sister’s death in 918. The Welsh, who also had to recognize Edward as an overlord above their own king, grew weary of Anglo-Saxon dominance. Welsh-Mercian discontent was assuaged shortly before Edward’s death. Whether this constituted widespread violent revolt is still a point of contention. Nevertheless, by the end of his rule in 924, only Northumbria was under Viking control.

Edward’s son, Æthelstan, still had treacherous political waters to navigate, and his rule would involve significant dealings with the Scots of Scotland (or Alba, as the Scots called it), the Britons of Strathclyde, and the Norse-Gaels of the Kingdom of Dublin as they grew wary of Anglo-Saxon expansion.

Æthelstan’s Ambition

Æthelstan followed an aggressive and expansionist policy that was a cause for alarm among his Viking, British, and other Celtic neighbors. In 927, he marched against the Vikings in York and took the city. This was the end of the last Viking kingdom in England, and the first time all of England was ruled by an Anglo-Saxon king. In 927, He styled himself “King of the English.”

In 934, he invaded Scotland and forced its king, Constantine II, as well as Owain, the ruler of the kingdom of Strathclyde, to submit to his suzerainty. Despite the success of his campaigns, there were still sizable elements of Viking, Celtic, and British power that resented his rule and were powerful enough to challenge it.

Thus began the formation of the Great Army, an unlikely alliance between the Kingdom of the Scots, Strathclyde, and the Vikings. Owain of Strathclyde and Constantine II of Scotland made a pact with Olaf Guthfrithson (also called “Anlaf”), the Viking king of Dublin, who sailed his fleet east in 937 to retake York. The fleet was large and contained, according to early 12th-century historian Symeon of Durham, 615 ships, although this number is likely an exaggeration.

There is scant knowledge of the lead-up to the Battle of Brunanburh, and it is likely there would have been a short window of opportunity for the Viking and Celtic armies to meet up. Well aware of the military situation, Æthelstan had assembled a large army of West Saxons and Mercians and then headed north to confront the enemy. The sizes of the armies are unknown, but the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle states that, “never yet as many people killed before this with sword’s edge… since the east Angles and Saxons came up over the broad sea,” likely indicating that the opposing armies were of considerable size for the time.

Brunanburh, 937 CE: A Savage Battle

Like the events leading up to the battle, much of what is known about the Battle of Brunanburgh comes from poetry and sources that cannot be relied upon for being completely truthful. One of the major mysteries is where exactly the battle was fought. Over 40 places have been suggested! Many medieval sources suggest somewhere in York, while the Wirral Peninsula opposite the present-day city of Bromborough near Liverpool is also a popular option. Bromborough is thought to be a derivation of Brunanburh, and medieval weaponry from both the Norse and the English have been found in the area, although it is argued that this is not conclusive, given the fact that metalwork from the era was all over England, and there were many places that could have been named “Brunanburh.” The case for Wirral is supported by the fact that it is also a very short distance to sail from Dublin. To get to York, the Norse and their allies would have had to sail to the other side of England. Given the Viking sailing skills, however, this was not too difficult a proposition. It just would have taken longer.

While the Annals of Ulster describe the battle as “great, magnificent, horrible,” and “savagely fought,” much of today’s knowledge is derived from the Old English poem, “The Battle of Brunanburh,” found in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. It was written shortly after the battle in 937 CE. The poem claims the battle lasted throughout the entire day, from sunrise to sunset, and that the fields “grew slickened with the blood of men.” At the end of the day, the ground was littered with corpses, left for the carrion birds, and the Anglo-Saxons were victorious.

There lay many warriors, seized by the spear,

the northern men, over their arrowed shields,

likewise the Scottish also were weary, saddened by war.

The West-Saxons in their ranks rode down

the long long day the hateful people,

chopping down the battle-fleers from behind

so sorely with sharply ground swords.(Click here for full text of the poem)

The poem states that “Anlaf” escaped to his ships, while both he and “Constantinus” lost a great deal of their men, with the latter losing his son to the slaughter. The poem also mentions that five kings were slain, as well as seven of Olaf’s earls. Their identities are not known. If these casualties are to be believed, it is highly likely that the Scottish and Viking losses were immense. The fate of Owain is not mentioned in the poem, but he is mentioned in other works as being alive after 937.

The Aftermath of Brunanburh

Forged in blood and steel was a victory that proved the united purpose of the Anglo-Saxon peoples, whether from Wessex, Mercia, or any other Anglo-Saxon region. Æthelstan’s power was consolidated, and he became more widely accepted as the king of all Anglo-Saxons, thus preventing any chance of the dissolution of the single Anglo-Saxon polity. Their various enemies, although significantly weakened, would recover over the decades and continue to pose a threat to the Anglo-Saxons for several centuries.

There are, however, detractors to this narrative. Historian Alfred Smith argues that while the battle was the most important battle in England before Hastings, its relevance has been overstated. Historian Alex Woolf argues that the outcome was actually pyrrhic and that this is proven by the fact that after Æthelstan died in 939, Olaf took Northumbria. The Northumbrians only accepted southern rule after expelling their leader, Erik Bloodaxe, in 954.

Whatever the outcome and its importance may have been, Brunanburh lives on as an epic tale in the long story of England and is part of a narrative, true or not, that formed the foundation of the English nation.