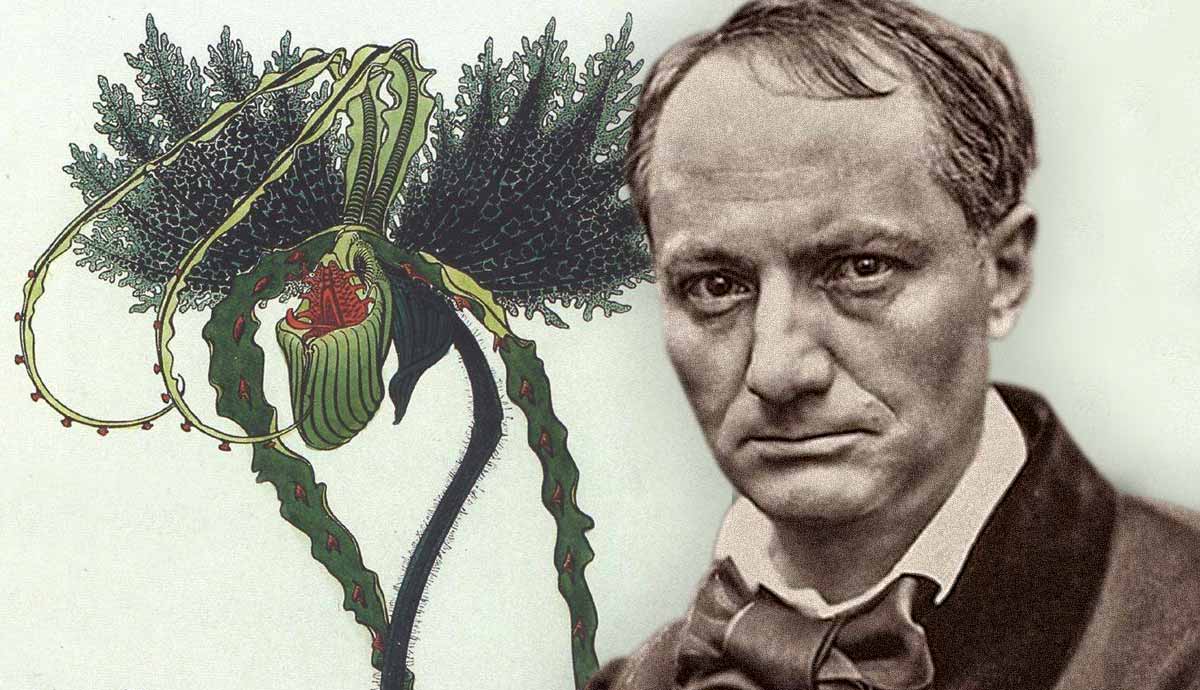

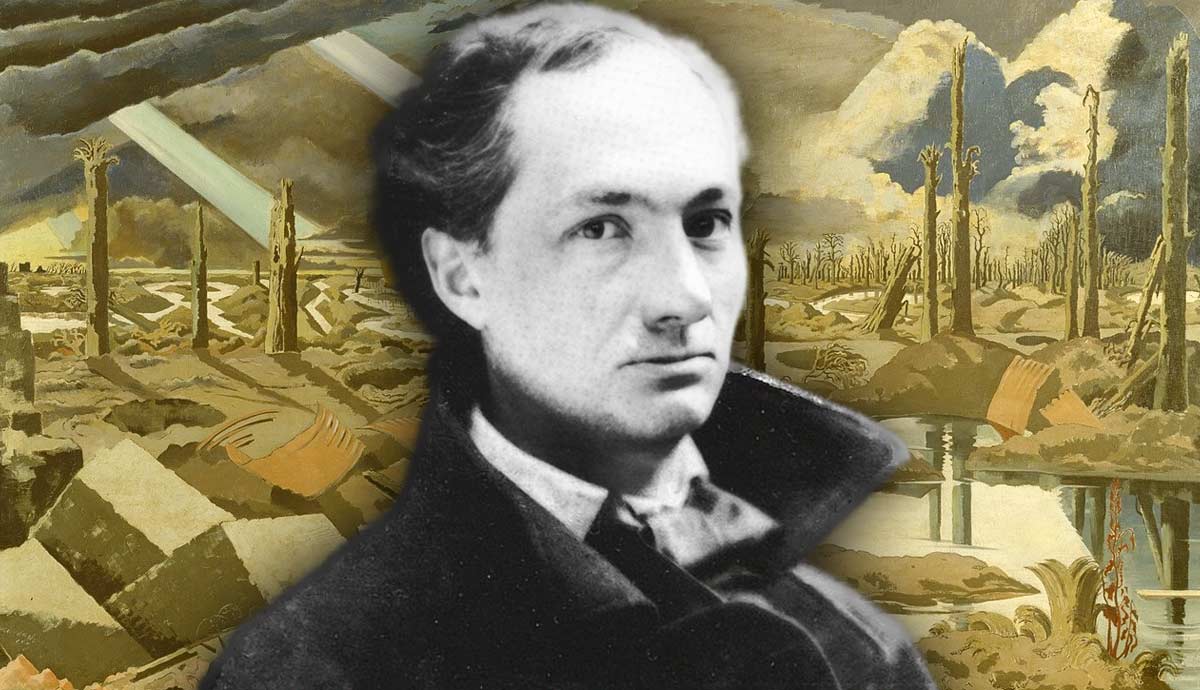

If any poet has a claim to be called the godfather of decadence, it is Charles Baudelaire. Thirty years before the literary movement which celebrated decay and perversity, Baudelaire’s writing—especially the poetry collection Les fleurs du mal, or The Flowers of Evil—was the blueprint. The poet courted scandal by writing about transgressive subjects such as the allure of putrefaction, vampirism, lesbianism, and Satanism. Although the initial response in France was an outcry, poets across the seas gradually became fascinated by Baudelaire’s words and ways.

Les fleurs du mal: Publication and Reception

Charles Baudelaire published Les fleurs du mal in 1857. It was his first (and ultimately only) volume of poetry, and it brought greater attention to a young poet who was beginning to attract interest among Parisian literary circles for his Bohemian eccentricities.

With Les fleurs du mal, Baudelaire achieved the ultimate goal of the Bohemian artist, to “épater les bourgeois,” or scandalize the middle classes. The volume was immediately prosecuted by the censors because of its provocative content. Baudelaire and his publisher were ordered to remove six of the poems, including ‘Lesbos,’ ‘The Metamorphoses of the Vampire,’ and ‘Women Doomed.’

Despite the removal of these poems, which were considered objectionable because they dealt too openly with women’s sexuality, Les fleurs du mal, in its expurgated form, remained transgressive in other ways. Its opening poem, ‘Benediction,’ envisions the poet’s mother lamenting that she has brought into the world a “hideous Child of Doom,” comparing him to the “pestilential blossoms” of a “wretched tree.”

This sets the tone for a collection that sees nature’s perverse side, whether in the natural world or human nature. Baudelaire is interested in decay, not growth; in women’s bodies as sources of disease, not new life; in God as an “Almighty who bestowest pain,” not a benevolent creator. The poems are not wholly pessimistic, but when they do celebrate something, such as beauty in the poem ‘Hymn to Beauty,’ it is an ambivalent celebration. The poet is conscious that his obsessive pursuit of beauty might be driven by diabolical, rather than divine, inspiration.

How Baudelaire Came to England

English readers would have to wait until 1909 to read Les fleurs du mal in translation. However, this did not prevent Baudelaire’s poems from exerting an influence on poetry written in English over the course of the second half of the 19th century.

One of Baudelaire’s most enthusiastic English readers was Algernon Charles Swinburne, who managed to replicate the succès de scandale of his French precedent with his own Poems and Ballads (1866). Swinburne’s collection touched on eroticism, sadomasochism, lesbianism, and hermaphroditism, as well as subverting Christian beliefs and traditions in the way Baudelaire’s poems had.

Like Baudelaire, Swinburne was as committed to traditional poetic forms as he was to transgressive poetic subjects. His poem ‘Sapphics’ is so named not only because it deals with the poet Sappho, but because it employs the Sapphic stanza: verses of four lines each, the first three comprising eleven syllables, and the final line comprising five. When Baudelaire died of syphilis in 1867, aged just 45, Swinburne wrote the elegy Ave Atque Vale, complete with an epigraph from Les fleurs du mal.

Another poet inspired by Baudelaire’s subjects and style was Ernest Dowson, a member of the Rhymers’ Club, founded in 1890 by Ernest Rhys and W.B. Yeats. Dowson’s 1894 poem Cynara, about a doomed affair, employs alexandrines, or lines of twelve syllables, which are more commonly found in French poetry than English. (Baudelaire often uses this highly regular meter in ironic conjunction with perverse subject matter in Les fleurs du mal). Dowson’s poetic career was short-lived, but Cynara was the origin of the phrase “gone with the wind.”

The Rhymers’ Club was associated with the literary movement of decadence and made up of several poets who contributed to the infamous magazine The Yellow Book. So-called because scandalous French novels were published in England with discreet yellow covers that hid their title and author, The Yellow Book revealed the influence of all things French on the decadent movement.

One Yellow Book contributor, Arthur Symons, was among the first English critics to advocate for Baudelaire. Symons was also one of the first critics to define the decadent movement of the 1890s, in terms which suggest Baudelaire’s importance as a forefather. Decadent literature, a “new and beautiful disease,” according to Symons, is characterized by “an intense self-consciousness, a restless curiosity in research, an over-subtilizing refinement upon refinement, [and] a spiritual and moral perversity” (Munro 1963).

These were qualities which preoccupied poets of the Rhymers’ Club such as Dowson, Symons, Lionel Johnson, Lord Alfred Douglas, and Douglas’s lover and occasional attendee, Oscar Wilde. While Wilde’s poetic inspirations were varied, Baudelaire appears frequently in his criticism, providing a precedent for his preoccupation with paradox—making nature unnatural and adopting the artificial as authentic.

Poetic Personae: Dandies, Bohemians, Poètes Maudits

Baudelaire’s influence on late-19th-century poetry in English went beyond words on the page. Wilde’s poetic persona would be unimaginable without Baudelaire, who was among the first to adopt a series of stances on life and art that we now associate with the poetic sensibility.

The Romantic movement of the early 19th century had gone some way towards establishing the poet as an outsider, remote from society, but still with some useful role to play. In the perverse spirit of his poetry, Baudelaire took this position and re-envisioned it, celebrating the poet’s difference precisely because it was oppositional.

The poet was an individual within the crowd, part of the social body but irremediably distinct from it. This is the poète maudit (the accursed or damned poet), an early-19th-century term for poets who transgressed the bounds of polite society.

In Baudelaire’s writing, the poet roams the city, observing people and phenomena from all walks of life, taking only a minor part in things himself. He is devoted to beauty, and (like the Romantics) he continually, restlessly pursues an unknown ideal, but he is indisposed to any kind of useful action. He may be rich and collect artistic objects or spend his money on dressing impeccably. This is the poet as a dandy, a persona on which Baudelaire mused in his essay The Painter of Modern Life (1863), and which Wilde made popular in his plays, novel, and person.

Since the increasingly philistine society he lives in does not value art as he does, Baudelaire’s poet may even be poor. Nonetheless, his devotion to art ennobles him: this is the poet as a Bohemian, a persona made popular in mid-19th-century Paris.

Baudelaire successfully blended the dandy and Bohemian, making it irrelevant whether he was rich or poor, or even whether his poetry was actually worth reading. Like Wilde after him, he was a master of publicity, capturing interest by seeming to fulfil the ideal image of the poet before his first volume was even published.

The Doctrine of Correspondances

Baudelaire’s poetic interest in evil and Satanism prefigured many decadent works, but his approach to spirituality in Les fleurs du mal is complex. Rather than a sole focus on evil, it would be more accurate to say that his poems prefigured the late-19th-century interest in the occult and mysticism.

In Correspondances, Baudelaire expresses a belief in nature as a “temple,” possessing some kind of unity, just not the kind proposed by Christian doctrine. Instead, Baudelaire is interested in the synesthetic experience nature affords, the way that “perfumes, colors, sounds may correspond.” There are odors, he writes, “fresh as a baby’s skin, / Mellow as oboes, green as meadow grass.” All of our senses, and therefore all aesthetic experiences, correspond.

It is no surprise, then, that Baudelaire was one of the first Wagnerites—who viewed the composer Richard Wagner’s works as the apex of a unified aesthetic experience—and a major influence on Symbolist poetry and art. The Symbolist Manifesto, published in France in 1886, named Baudelaire as one of the leading Symbolist poets, despite the fact that he had been dead for nearly 20 years.

Wagnerism and Symbolism, along with the Baudelaireian influences in both, reached English shores in the last couple of decades of the 19th century. By this time, Baudelaire’s doctrine of correspondences between the arts had filtered through to another movement, more prominent in English poetry: Aestheticism. This movement, which prized art for art’s sake in the dandyish manner of Baudelaire, also celebrated the range of synesthetic experience he had written about in Correspondances.

Oscar Wilde was not only influenced by Baudelaire’s persona. He took up the doctrine of correspondences throughout his work. The eponymous protagonist of The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891) is devoted to understanding correspondences through immersive sensory experience. Similarly, Wilde’s play Salome (1893), with its musical lines and focus on light, color, and the sound of language, was overtly Symbolist. It would have been the first and most infamous Symbolist play in English, but it was in fact originally written in French, in recognition of the French tradition to which it was indebted.

The Poet of the City

In 1861, Baudelaire published a second edition of Les fleurs du mal. The censored poems remained absent, but this edition featured a new section titled ‘Parisian Scenes.’ These poems cemented Baudelaire’s reputation as an urban poet who uniquely understood how the conditions of city living shaped human experience.

Since 1853, Baron Haussmann had been overseeing the reorganization of Paris, doing away with crowded, ramshackle medieval neighborhoods and instituting clean, geometrically arranged streets and squares. In poems such as ‘The Swan,’ Baudelaire’s all-seeing poet roams these new streets, physically immersed in them and saturated with their detail, but spiritually detached.

Modernization, for Baudelaire, does not necessarily equal progress. It has swept away the diverse, downtrodden characters who gave flavor to his earlier poems. The city is so clean, new, and anonymous that it sickens and alienates the poet. Things have not moved forward so much as led to decay.

The late-19th-century decadent poets in England were overwhelmingly, like Baudelaire, poets of the city. While their Romantic antecedents had looked to nature for inspiration (most famously, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge took up residence in the Lake District), the decadents saw their inner worlds reflected in the busy streets, crowds, transports, and new technologies of the city.

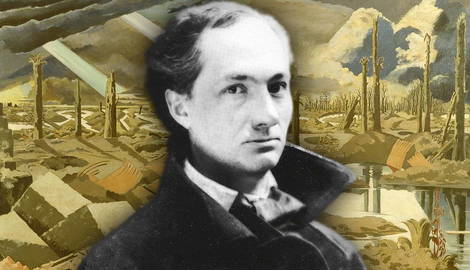

Baudelaire’s legacy as poet of the city is most evident in T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (1922). One of the poem’s most memorable passages sees the poet walking through the crowds of the “Unreal City” of London, oscillating between descriptions of the urban setting and internal musings. Openly signaling the influence of Baudelaire on this passage, Eliot includes a quotation from the preface to Les fleurs du mal: “Hypocrite lecteur! – mon semblable, – mon frère!” (“Hypocrite reader! – my doppelganger, – my brother!”).

The Modern Poet

Baudelaire’s Fleurs du mal anticipated modern poetry in its daring approach to its themes, shying away from nothing, no matter how shocking it might have been to mid-19th-century sensibilities.

Beyond his avant-garde taste for risqué subject matter, Baudelaire is also seen as distinctly modern because his poetry reflects the dark underbelly of a world we can recognize. The human condition in Baudelaire is fickle, prone to fits of anger, ennui, obsession, and yearning, but infinitely curious about everything in his urban environment, from fleeting fancies to grotesque back-streets.

Much of Les fleurs du mal was formally and metrically conventional, despite the transgressive subjects. However, elsewhere in his writing, Baudelaire paved the way for the modernist experimentations of the 20th century.

His posthumous 1869 collection Petits poèmes en prose was published in English in 1913, in a translation by Arthur Symons. In its preface, Baudelaire writes of his hopes to carry off “the miracle of a poetic prose, musical without rhythm and without rhyme, supple and staccato enough to follow the lyric motions of the soul” (Baudelaire 1913, 5).

The ‘poem in prose’ was a non-metrical vehicle for poetic ideas, and was taken up in English by Oscar Wilde in the 1890s. Baudelaire’s mission to express poetic ideas without the constraints of rhyme and meter opened the doors for 20th-century poets, too, to see poetry as a frame of mind or sentiment, not just a form.

Les fleurs du mal, though, remained Baudelaire’s most celebrated achievement, and continued to influence poets into the 20th century. In 1936, it was translated by the poets George Dillon and Edna St. Vincent Millay. These translations also appeared in a 1940 volume compiling translations of Les fleurs du mal by various poets, including Arthur Symons, Lord Alfred Douglas, Aldous Huxley, and the Harlem Renaissance poet Countee Cullen.

Baudelaire’s ability to blend the beautiful and the perverse also inspired lyricists who began their careers as poets. Jim Morrison of The Doors took a Baudelaireian view of life in his songs, fascinated by darkness and disease, and Patti Smith counts Baudelaire among her literary heroes.

Bibliography

Baudelaire, C. (1913). Poems in prose from Charles Baudelaire; translated by Arthur Symons. E. Mathews.

Munro, J.M. (1963). “Arthur Symons as Poet: Theory and Practice”. English Literature in Transition 6 (4): 212–222.